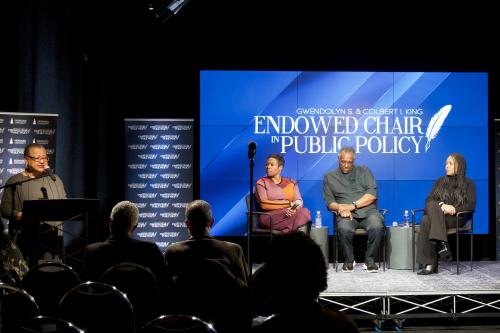

On Feb. 11, the Gwendolyn S. and Colbert I. King Endowed Chair Lecture series returned with “Reimagining Public Education, Part II: Policy, Power and the Future of HBCUs,” a conversation that centered higher education’s shifting terrain and the outsized influence historically Black colleges and universities can wield both for their core constituency and the broader academic landscape.

Moderated by Melanie Carter, Ph.D., associate provost and director of Howard University’s Center for HBCU Research, Leadership, and Policy, the program traced how decisions made beyond campus through legislation, philanthropy, and workforce strategy directly shape the student experience. Carter spoke directly to why this conversation especially matters today.

“[Educational historian] Joel Spring said that K-12 public schools were the most available public education; most people have had some experience with public education, and therefore speak with some authority about it,” Carter said. “The same is true with HBCUs in terms of our experiences with our institutions. Not everyone has attended an HBCU, but it is rare that you find someone that’s not been touched by one.”

“HBCUs certainly permeate every living creation of the American experience as we think about all these issues around democracy, policy, civics, and all the things that are so important,” Carter added.

“Policy is imbued in nearly every aspect of our lives,” said Trustee Emerita and 2025-2026 King Endowed Chair Marie C. Johns. “That’s what this series is attempting to do, talk about those key issues for our community and the policy implications that are embedded there.” (Photo: Simone Boyd/Howard University)

Opening Remarks Frame HBCUs as Essential, Not Peripheral

The formal program began with remarks from Tonjia Hope Navas (Ph.D. ’24), assistant provost for international programs, and Trustee Emerita Marie C. Johns (DHL ’13), the 2025-26 King Endowed Chair holder. They both framed the conversation as timely and necessary, an invitation to think expansively about where higher education is headed and what it will take for institutions rooted in a mission to shape that future rather than simply respond to it.

Hope, on behalf of Interim Provost and Chief Academic Officer Dawn Williams, Ph.D., spoke to the historical essence of HBCUs and how that history informs their standing today.

“When we speak of the future of HBCUs, we are speaking of institutions that have always existed at the center of these tensions,” Hope said. “HBCUs are not peripheral to the future of education; they are essential to it. They have long modeled what it means to educate the whole student. They have demonstrated how policy can be leveraged to advance equity rather than entrench disparity. And we know that they continue to produce leaders, educators, policymakers, entrepreneurs, and public servants who understand that education is both a private good and a public trust.”

In her opening, Johns underscored the purpose of the endowed chair lecture: to create space for rigorous, solutions-oriented dialogue that does not sidestep complexity, particularly when the stakes include access, public policy, and systemic progress.

“My approach to this series this year was that we could go 10 miles deep on issues of public finance or international diplomacy, but I thought it was important to approach policy from an every man, every woman perspective, and that is really trying to drive home the point that policy is imbued in nearly every aspect of our lives,” Johns said. “That’s what this series is attempting to do, talk about those key issues for our community and the policy implications that are embedded there.”

From Advocacy to Investment: Building Power That Matches Impact

The panel featured voices spanning campus leadership, national advocacy, public policy, and workforce strategy: Denise Jones Gregory, Ph.D., interim president of Jackson State University; Harry L. Williams, president and chief executive officer of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund; Lodriguez Murray, senior vice president of public policy and government affairs for the United Negro College Fund (UNCF); and Kayla C. Elliott, Ph.D., director of workforce policy for the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies.

Across the discussion, a shared premise emerged: Policy is not abstract. It becomes real through budgets, research investments, accountability frameworks, and partnerships that either expand or constrain institutional capacity. The panelists emphasized that HBCUs have long delivered impact disproportionate to resources, and that the question is whether systems of power align with what HBCUs already prove to do well without equitable means.

“HBCUs are stronger now than they’ve ever been. We’re coming from a position of strength, not a position of deficit,” Harry Williams began. “This is a great opportunity for us to really engage and talk about the many positive things happening and not be sleeping as it relates to where we are and how we move. Not only at this great institution here, but how we bring the whole ecosystem of HBCUs along.”

Murray introduced himself as the first UNCF executive to have been a UNCF scholarship recipient and spoke to how his personal experiences inform how he shows up in his position. His comments focused on policy levers and what it looks like to translate national attention into structural wins for students and institutions.

“[UNCF] is one of the few things in [D.C.] that Democrats and Republicans can agree that they want to support, and we’re able to do that because we changed the way that we talk about HBCUs,” Murray said. “We started talking about economic impact … that gets their attention. And when you get their attention, then you can put your policy objectives on the table, put pen to paper, and receive good outcomes.”

[HBCUs] are around for people like you and I to be able to stand where we are right now, to be able to do what we do every day, and that is make a difference in the world.”

From the institutional perspective, Gregory, now stewarding her alma mater, spoke to the practical realities of stewarding a campus amid shifting expectations while keeping students centered: ensuring composure, strengthening infrastructure, and sustaining a culture where achievement is the standard.

“HBCUs provide stability; there’s a place that’s always stable in terms of where people can come and find a place that they can call home,” Gregory said. “I look back at my journey at Jackson State and say, ‘Wow, I never thought that I would be able to stand in front of you and say that I’m the interim president,’ and it’s because of what was poured into me while I was there.

“[HBCUs] are around for people like you and I to be able to stand where we are right now, to be able to do what we do every day, and that is make a difference in the world.”

Elliott connected the conversation to the future of work, emphasizing that the proper partnerships can serve as accelerants when designed to expand opportunity, and that requires being privy to and part of key planning discussions.

“How are we expanding the conversation and looking at policy that’s not specifically about us, but that absolutely impacts us?” Elliott said. “Every higher ed issue is an HBCU issue. We have to be in every conversation. The nerdy, wonky, metric conversation — one of us has to be there. The philanthropic rooms where they are talking about who is getting what, we absolutely have to be there.”

Reflections Underscore Stakes, Path Forward

Following the panel, the program turned to reflections from Omari H. Swinton, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Economics at Howard University, and William Godwin, a doctoral student in higher education leadership and policy studies.

Swinton shared his personal perspective as the son of a former HBCU president who grew up on HBCU grounds, describing how firsthand exposure shapes an understanding of the brilliance, care, and rigor that HBCUs cultivate.

“I’m an HBCU researcher now, and an economist doing research on HBCUs was kind of frowned upon, like why do you care about this small subset of universities?” Swinton shared. “But these universities punch above their weight. Alumni talk about the financial benefits, but each of these schools can go to their community and talk about the individual benefits they give.”

“Not every HBCU is growing, but a lot of them are, and the reason they’re growing is because they’re doing a good job at educating their students, and people who see their students see value in where they’re at,” Swinton added. “This is an important policy point: HBCUs are all different, and the ones who need the extra help, we have to support more and think about ways that we as policymakers can make sure that they survive and are successful.”

Godwin reflected on what it means to study higher education policy while living within an institution whose history offers both evidence and instruction, underscoring that HBCUs are not theoretical solutions, but proven ones that warrant serious, sustained investment.

“One of the things I think I’m hearing is that when we get in positions of power, whether we’re in a non-profit organization, whether we’re leading an institution, or working in government, we have to speak up for institutions that we want to be at the center of the conversation and not on the margins,” Godwin said.

Godwin shared how his experience as a White House Fellow encouraged his doctoral pursuit, as he searched — and continues to as a student — for ways to make workforce development more equitable and prominent on HBCU campuses.

“I’m on a little private, personal campaign to get more of our institutions signed up, that we’re getting those dollars, that our faculty is getting that training and exposure, and that the curriculum is actually relevant for what the federal government wants,” Godwin said, “because when we talk about economic impact, that changes how Congress and government receives who we are and values what we bring to the table.”

Following January’s focus on leadership and equity, Part II sharpened the lens on the conditions that make leadership sustainable. From research and workforce development to civic leadership and economic mobility, panelists and respondents alike emphasized that HBCUs grow when resourced, represented, and included in important decisions. At this pivotal moment, the question is not whether HBCUs are ready; it is whether the broader ecosystem will meet them with the support their impact warrants.

(from l-r) Trustee Emerita Marie C. Johns, Dr. Melanie Carter, Dr. Denise Jones Gregory, Harry L. Williams, Lodriguez Murray, and Dr. Kayla C. Elliott (Photo: Simone Boyd/Howard University)

Keep Exploring

Howard University Hosts MLK Birthday Conversation on Leadership, Equity, and the Future of Learning

Trustee Emeritus Marie Johns, Sen. Angela Alsobrooks Open 2025-26 King Endowed Chair Series with a Call to “Elevate Our Voices”

Marie Johns Appointed Chair of the Gwendolyn S. and Colbert I. King Endowed Chair in Public Policy at Howard University

Keep Reading

-

News

NewsJoin the ‘Transformation to Triumph Black Women’s Summit’ and Become Part of a Global Network of Support

Feb 24, 2026 4 minutes -

News

NewsHU-MasterCard Inclusive Growth Thought Leadership Lecture Series Kicks Off Howard’s 2026 Data Week

Feb 20, 2026 5 minutes

Find More Stories Like This

Are You a Member of the Media?

Our public relations team can connect you with faculty experts and answer questions about Howard University news and events.

Submit a Media Inquiry