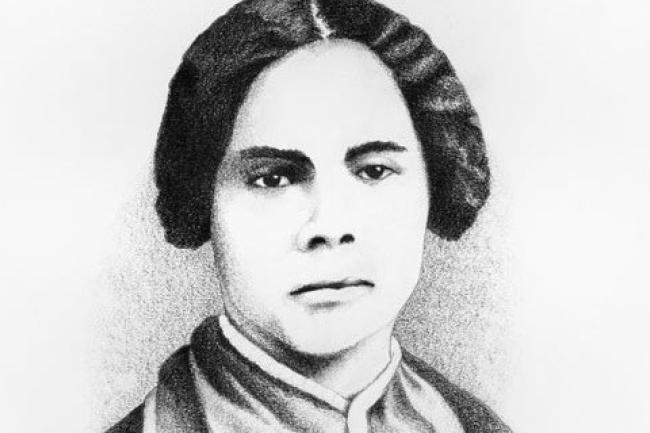

Mary Ann Shadd Cary is often known at Howard University as its first female law student and one of the first Black women to earn a law degree nationwide.

However, many miss the fact that she was a publisher, journalist, educator, and activist who stood tall alongside well-known contemporaries of the male-dominated abolitionist movement, and predominately white women’s suffrage movement, such as Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Shadd Cary set up a school for Black children in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and continued to teach throughout the northeastern United States until she moved to Canada in 1851.

Shadd Cary was born in 1823 in the free state of Delaware, where her abolitionist parents Abraham D. and Harriet Parnell Shadd ran their home as a station on the Underground Railroad. Delaware did not allow Black children to be educated, so when Shadd Cary was 10 years old, the family moved to Pennsylvania and sent their children to Quaker boarding school. This upbringing undoubtedly impacted Shadd Cary, who was seen as a rebel even in her own family of activists.

Shadd Cary set up a school for Black children in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and continued to teach throughout the northeastern United States until she moved to Canada in 1851.

When Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, the largest wave of Black migration to Canada in the 19th century was set in motion. Feeling that refugees would need her services, Shadd Cary and her brother Isaac migrated to Canada, and the rest of her family soon followed.

In 1851, she opened a school for the growing refugee population and taught racially integrated classes 100 years prior to the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling desegrated U.S. schools. In addition to teaching, she published her words broadly, encouraging Black people to emigrate from the United States to Canada while advocating for integrated education.

Shadd Cary's public arguments against segregated schooling caused a rift between her and the publishers of Voice of the Fugitive, Canada’s first Black-owned abolitionist newspaper.

After losing support from their publishers and the American Missionary Association, which funded her school, Shadd Cary began her own newspaper, The Provincial Freeman. This made Shadd Cary the very first Black woman to publish a newspaper in North America. The Provincial Freeman was the foremost voice of Black communities in Canada but, by 1859, she could no longer afford to publish.

Her husband, Thomas Cary, died in 1860, leaving Shadd Cary a widow with two children. Shadd Cary continued to struggle financially until her friend and fellow abolitionist Martin Robinson Delany offered her a job as a Recruiting Officer for Black men in the Union Army, making Shadd Cary the first Black woman to actively recruit troops. After the Civil War, she remained in Washington D.C.

Shadd Cary taught and attended classes at Howard University School of Law, where she was Howard’s first Black female law student and one of the first Black women to earn a law degree. Shadd Cary then joined the women’s suffrage movement.

To say that Shadd Cary was ahead of her time would be an understatement: while Anthony and Stanton opposed the 15th amendment on the grounds that it gave Black men the vote before white women, Shadd Cary both spoke in support of the amendment and criticized it for not giving women the right to vote. Furthermore, at a time when even abolitionists were wary of integrated education, Shadd Cary opened and taught at a racially integrated school.

In 1874, she and a group of women addressed the House Judiciary Committee regarding women’s right to vote. She continued to support Canada’s suffragists as well, attending a rally in 1881. Despite her boundary-pushing contributions to the pursuit of justice and equity for all, Shadd Cary’s legacy largely went ignored in the decades following her death in 1893.

“[Shadd Cary] gave to the world a hundred instances of female heroism, any one of which is sufficient to rescue her name from oblivion and place it in the category of similar characters like Grace Darling, Dorothy [sic] Dix, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman or Florence Nightingale,” wrote the unknown author of “The Foremost Colored Canadian Pioneer in 1850,” one of the many documents contained in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center’s Mary Ann Shadd Cary Collection.

Her Washington, D.C. home still stands as a testament to her place in history: the Mary Ann Shadd Cary Residence is located on 1421 W Street, NW.