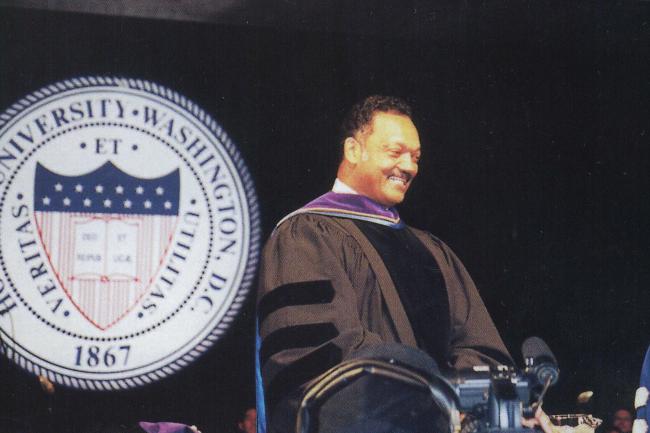

Because of the courageous life work and advocacy of Reverend Jesse Louis Jackson Sr. (D.H. ’70), the link in the chain of history that connects democracy and human rights is incalculably stronger. A titan of the Civil Rights Era, he served as a lieutenant in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, confronting segregation and discrimination, challenging economic inequities, pushing for voting rights, and forcing the nation to open doors of equality that he later walked through on his quests for the highest office in the land. His impact on the American political system was like an earthquake that shook its very foundations, and from its rubble a more inclusive process was built — one that more closely mirrored the principles expressed in the Constitution and Declaration of Independence. He held America to account for its treatment of all its citizens and was unyielding in his demands for unquestionable, unapologetic equity. His impact extended well beyond politics, however. Having grown up in poverty as the son of sharecroppers, Jackson ensured that young people embraced their full potential regardless of their socioeconomic background, leading crowds around the world in chants of "I am somebody." And when Jackson opened doors, he held them open for others to follow him through.

“What stood out most was his unwavering clarity of purpose, his moral courage, and his abiding faith in young people as agents of change,” said Wayne A. I. Frederick (B.S. '92, M.D. '94, MBA '11), interim president, president emeritus, and Charles R. Drew Professor of Surgery, in a statement to the Howard University community. “He believed, as we do at Howard, that each generation inherits both the responsibility and the opportunity to advance the cause of justice, and that leadership must be rooted in service and that hope must be made visible through action.”

Jackson’s presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988 were milestones in American democracy. In order to change the political system, he realized that the demographics of the electorate would have to change. Jackson’s aggressive voter registration drives enfranchised people from previously marginalized minority and LGBTQ+ communities, women, and disaffected white rural voters, many of whom have become consistent voters. By late March 1988, Jackson was the front-runner in the Democratic primary, an unheard of feat for a Black candidate. He forced the Democratic Party to change the way it made presidential nominations, allying with other leaders to award delegates more openly and transparently. But perhaps most impactful was just his highly visible example. Less than two decades after the passage of the Voting Rights Act, Jackson was the first Black candidate for president taken seriously by the political establishment. His courage, confidence, charisma, eloquence, and the depth of his ideas inspired countless future leaders to believe that they too could make a difference in this country.

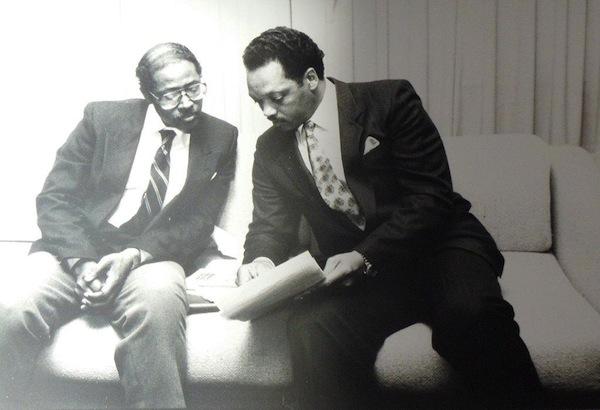

Clarence Lusane (M.A. ’94, Ph.D. ’97) worked on Jackson’s 1984 and 1988 campaigns before coming to Howard for graduate school and eventually becoming chair of the Department of Political Science. He followed in the footsteps of Ronald Walters, Ph.D., a longtime adviser to Jackson who also chaired Howard’s political science department and helped devise Jackson’s campaign strategies. Lusane remembers vividly Jackson’s work to bring people together.

“He was a unifier,” said Lusane. One of the things that was a strength of Jackson is that he brought together wildly different parts of the Black community in terms of politics. You had people who were Black nationals, people who were liberal, people who considered themselves socialist, women who considered themselves feminist — Jackson brought all of those communities together. He also reached out to farmers, people in the peace movement, people who were working on environmental issues, and people doing anti-nuclear work. He really had a vision of what eventually would be what he called the Rainbow Coalition — not just this group or that group, but people who could unite around a progressive agenda.”

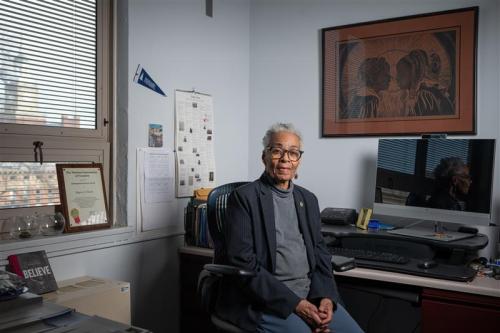

Walters taught at Howard for a quarter of a century and was one of the most respected political scientists in Washington, having worked with the Congressional Black Caucus in its infancy and serving as an architect of the anti-apartheid strategy related to South Africa. Jackson immensely respected Walters' knowledge of political processes and the nuances of the electoral system. Working with Jackson, Walters was instrumental in engineering a change to the process of selecting delegates who chose the Democratic presidential nominee, moving from a state primary system where each candidate who received votes in a given state received a proportional share of delegates from that state if they received a relatively high minimum percentage of the vote to a system where candidates could receive delegates even if they received fewer votes. Each of those delegates had a voice in shaping the party's infrastructure, and the new system allowed candidates like Jackson to earn a significant number of nominating convention delegates even if they didn't win the primary. Those delegates, in turn, could shape the rules of the party and its nominating convention. It gave Jackson tactical leverage inside the party, and his delegates were able to force through changes to the party platform and other significant policies. Members of Jackson's political team eventually became highly influential officials in the party and in the government. Ronald H. Brown (LL.D. '93), for example, led Jackson's 1988 convention team before becoming Democratic National Committee Chairman and then United States Secretary of Commerce in the administration of U.S. President William Jefferson Clinton (LL.D. ’13). Alexis M. Herman (LL.D. '97) also managed Jackson's convention teams and eventually became Clinton's United States Secretary of Labor. A constant and trusted consultant and confidant, Walters' work with Jackson changed the whole perception of advisers to a political campaign, according to political scientist Elsie Scott, Ph.D., who is the founding director of Howard's Ronald W. Walters Leadership and Public Policy Center.

"Ron Walters was the best known political scientist around," said Scott. "Reverend Jackson expected to win, and that's the reason he pulled in Ron Walters to plot the strategy needed to win the presidency. Once people saw that he could carry South Carolina and other states, they decided that they weren't throwing their votes away, because Jackson was out to win."

A close friend of Walters', Jackson ministered to him during his terminal illness and eulogized him at his funeral and burial. When the Walters Center was established, Jackson served as one of the first members of its Advisory Council. Today, the center remains an important voice in public policy development and analysis, carrying on the legacy of Walters and the spirit of Jackson.

"When some Black leaders were downplaying the ability of Rev. Jackson to run a credible race for President, Dr. Walters gave him data and policy analyses that supported the slogan, 'Run Jesse Run,' read a statement by Scott and Patricia Turner Walters, chair of the Ronald W. Walters Leadership and Public Policy Center. "In the words of Jesse Jackson Jr., 'Dr. Walters was the driving force behind the adoption of proportional allocation of delegates in the Democratic primary system.'"

Jackson set the stage for scores of formerly locked-out civic servants to have a seat at the table and forever changed the way we elect our leaders. Much of the system Jackson helped create is still in place today. U.S. President Barack Obama (LL.D. ’07, D.Sc. ’16), for example, used the proportional delegate system as his key to winning the presidential nomination in 2008 before eventually being elected president of the United States.

“A lot of the discussion about Rev. Jackson now is that he was wonderful, but when he ran in 1984, there was resistance from the Democratic establishment, from other church leaders, and from other civil rights leaders,” said Lusane. “But there was grassroots support. By the time we get to 1988, Jackson is really a power force in the party, and the Rainbow Coalition is really driving a lot of activism. He doesn’t win the nomination, but he changes the party. Jackson’s work to make the party more democratic in terms of the nomination process laid the foundation for Obama to win in 2008.”