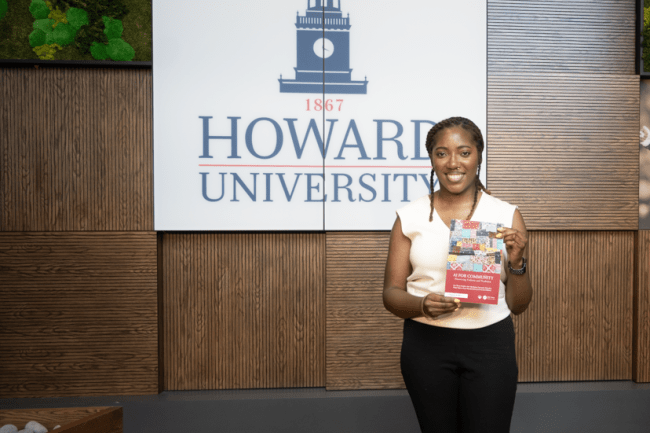

In the new book, “AI for Commuity,” researchers share how they've used AI to center humans and cultures, and provide a roadmap for using the technology to uplift rather than exploit.

Howard University Human-Centered AI Institute Senior Researcher Lucretia Williams authored one of the most prolific chapters in the book. Near the beginning of the chapter, she discusses FN Meka, the so-called “AI rapper.” Meka is a digitized animation, popular on TikTok, which raps using lyrics generated through artificial intelligence technology. Briefly signed to Capitol Records in 2022, it was widely criticized for stereotypes of Black people.

Instead of immediately focusing on the technology itself, however, Williams uses this instance as a jumping off point to discuss growing up in the South Bronx, about housing discrimination and landlord arsons, about the birth of hip-hop and the gatekeeping of white music executives. In this way, she helps the reader understand the environmental context, real people, and life circumstances with which the AI must coexist.

This constant focus — not just on AI but also on the communities it impacts — is at the heart of the new book. Featuring technologists, journalists, artists, and other experts, each chapter explores uses of AI to serve society, including preserving Fiji cultural traditions and endangered languages across the world, ensuring Black users are understood in their own dialects, or responding to global challenges such as Covid and climate change.

Writing for all communities

What unites all of these far-flung AI uses, according to Williams, is the community aspect apparent through the tone of the book. Even when discussing highly technical subjects, the authors maintain a focus on storytelling and the humans at the center of the dozens of case-studies used throughout.

"As the book itself is ‘AI for Community,’ we wanted to make sure our various communities actually would be able to pick it up and really understand it and parse through it."

“As the book itself is ‘AI for Community,’ we wanted to make sure our various communities actually would be able to pick it up and really understand it and parse through it,” Williams explains. “Our goal is to have this as part of curriculum, maybe in the class or in research labs, but we also if someone is interested in AI and what it does for their community or what it can do, we want them to be able to pick up the book.”

Rather than shy away from skepticism of AI or its potential and real harms, the chapters of the book are careful to present both the successes and limitations of the technology through the case studies. AI researcher and storyteller Davar Adalan, for example, describes the personal and scholarly significance of preserving and continuing the work of her mother, Sufi scholar Laleh Bakhtiar, through an AI chat, as well as the way a virtual “Beyond the Stars” experience helped young children in Fiji connect to their culture and art on a deeper level.

In the same chapter, however, Adalan also takes time to address the lack of robust, culturally nuanced datasets that underrepresented groups not only trust but feel they have ownership of. This limitation leads to everything from inaccurate and insensitive information on indigenous cultures to medical misdiagnoses for entire communities.

Agency, Trust, and Community Empowerment

Throughout her career, Williams — who describes herself as a community researcher first — centers autonomy and trust. During her time in South Africa, this meant working directly with child home-care workers in low-income communities for weeks to fully understand their work, their community, and their day-to-day lives. By giving them a voice in the project from the beginning, Williams and her team created a WhatsApp chatbot tool for early-childhood assessment that was not only fine-tuned to the needs of the workers, but also provided a sense of personal ownership and pride.

Williams’ more recent work at Howard takes her efforts to give people a voice a step further, as she and her team literally recorded Black voices from around the country to inform the development of AI voice recognition technology. A collaboration with Google, “Project Elevate Black Voices” comprises roughly 600 hours of recordings of Black people speaking in their natural dialects. This is a huge step toward solving issues Black users continue to face when using speech-recognition technology, which often forces them to code switch to be understood. The recordings are owned by Howard.

The researchers, who made the database available for HBCU researchers, were careful to weave agency and a sense of ownership throughout the project, taking time to meet with members of each community, incorporating references to Black culture and ways of speaking into their questions, writing newsletters for participants and guidelines for any institution that will use the dataset, and even compensating participants — something extremely rare in an era of unchecked data access.

“As a human-centered researcher, I constantly grapple with the question, ‘Are we going about this the right way?’” Williams writes. “I wholeheartedly believe that Black people should be included in the development of future technology, and when it comes to AI, that means inclusive data. Institutions of power having Black people’s data in their hands historically has never ended well. But the way the future is going, Black people will easily become excluded and further the usage and digital divide.”

As it works into more and more of our work, our lives, and our culture, artificial intelligence can appear as an overwhelming force — one that’s often predatory, hostile, and alienating. This is especially true for Black and indigenous people, and other communities for whom technology historically works to reinforce structural inequality. “AI for Community,” then, is an important milestone, laying out steps researchers, companies, institutions, and communities can take to build a world where AI is a tool not for greater control and exploitation, but for human flourishing, for all.