Over the past 250 years, education of students of color has evolved from an exercise forbidden by law and punishable by death into one which has, at least ostensibly, been embraced by the country’s leaders at the highest levels. As one of only six congressionally chartered universities in the United States and the only such-chartered historically Black college or university, Howard has been central to the intellectual, cultural, athletic, and scientific fabric of the nation since its founding in 1867 and a frequent destination for U.S. presidents.

Presidents’ Day is an annual reminder of how deeply Howard is ingrained in the fabric of the country. As evidenced by numerous visits by a succession of U.S. presidents, Howard has maintained its influence at the highest levels during pivotal periods in American history. Some presidents delivered inspirational and profound remarks, while other presidential sentiments have not held up as well by today’s standards. There is no doubt, however, that few institutions have received similar attention from a succession of presidents who endorsed Howard’s singular position as a beacon of opportunity.

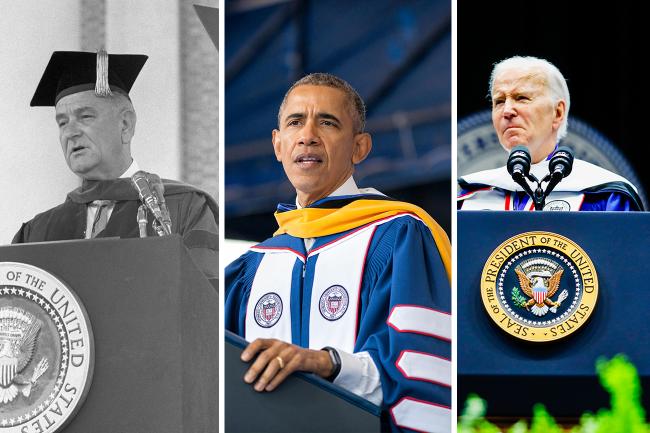

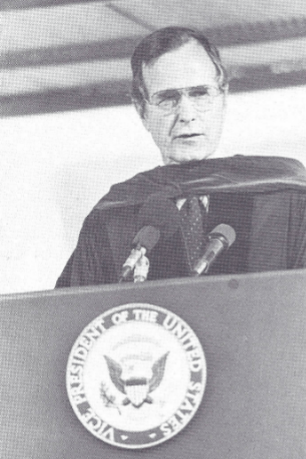

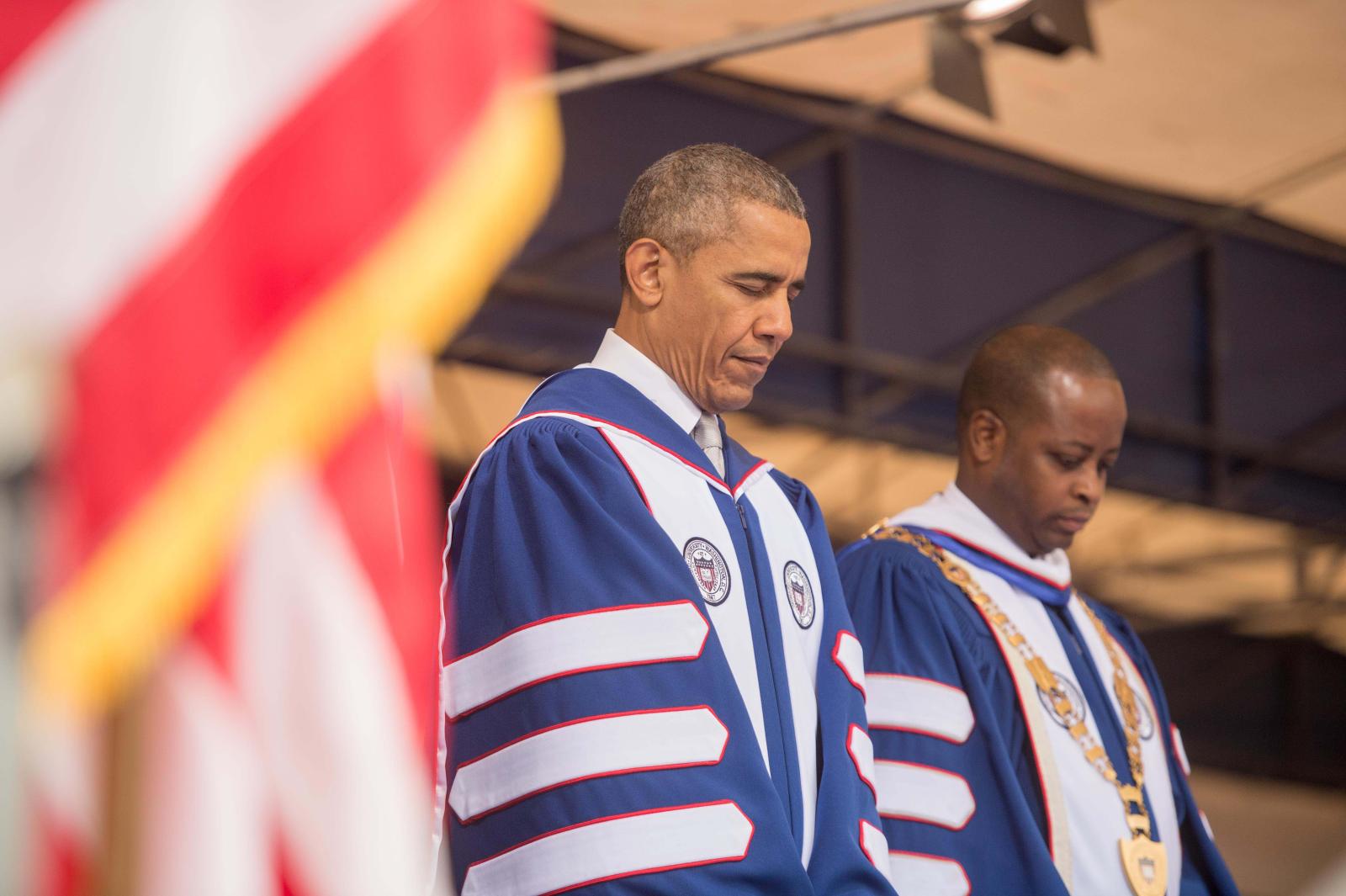

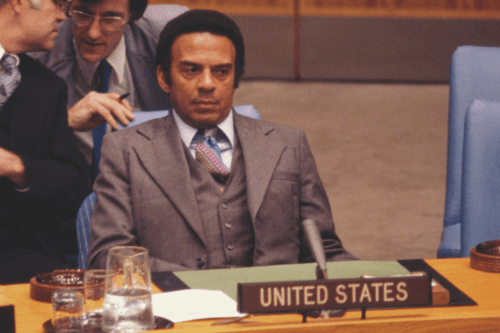

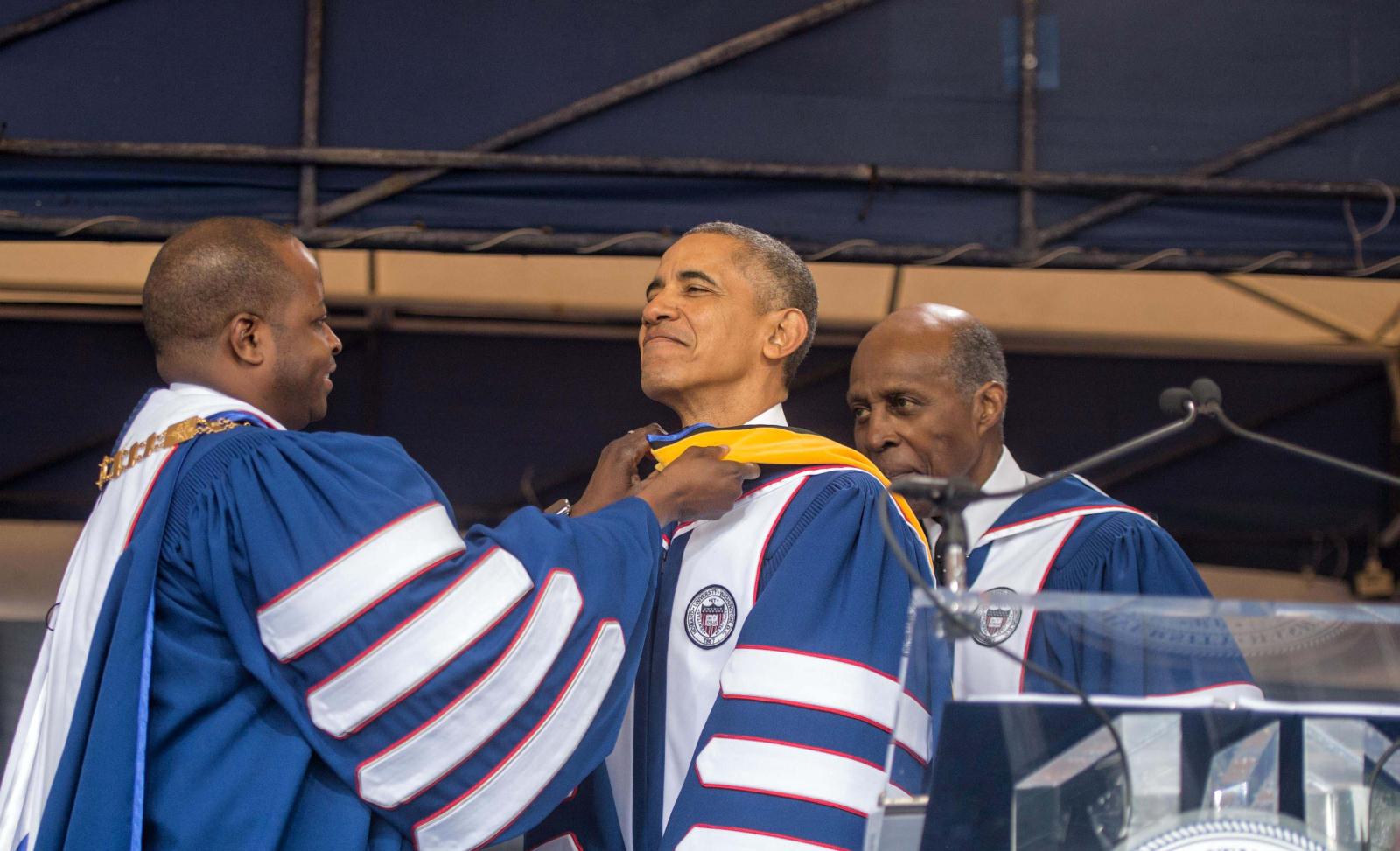

Nine sitting presidents — Rutherford B. Hayes, William Taft, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson (LL.D. ’65), Ronald Reagan, William Jefferson Clinton (LL.D. ’13), and Barack Obama (LL.D. ’07, D.Sc. ’16) — spoke on campus. Two other sitting presidents, Theodore Roosevelt and Joseph R. Biden (DHL ’23), spoke at Howard Commencement Convocation ceremonies off campus. Future presidents spoke on campus included Richard M. Nixon, John F. Kennedy, and George H. W. Bush (LL.D. ’81) and a former president, Dwight Eisenhower, visited campus to champion one of his signature programs. Johnson, Bush, Clinton, Obama, and Biden hold honorary degrees from Howard.

"Our university’s location in the heart of the nation’s capital certainly attracts presidential visits, but it is essential that we recognize that these visits are far more than ceremonial," said Benjamin Talton, Ph.D., executive director of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center and professor in the Department of History at Howard University. "As many presidents have acknowledged in their remarks on campus, Howard’s history is intricately woven into the fabric of American history. Since Howard’s founding there has been an ongoing dialogue—at times contentious and fraught, and at times of one accord—between the university and the nation’s presidents and the government more broadly."

Here’s a look at the engagement of presidents of the United States at Howard and with the Howard community. Note that this article references remarks which refer to Black people as “colored” and “Negro” in the context of standard nomenclature during various times in American history.

In February 1878, the 19th U.S. president, Rutherford B. Hayes, visited Howard at the invitation of Frederick Douglass (LL.D. ’1872), one of the institution’s first trustees, who was appointed by Hayes to serve as U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia. Just over a decade after the university’s founding, Hayes and Douglass attended a dinner on campus to help present a steel engraving of a Francis Carpenter rendering depicting the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln. Hayes challenged students to labor hard and save in order to become self-sufficient.

“My young colored friends, let this, then, be among your good resolutions: ‘I will work and I will save, to the end I may become independent,’” said Hayes.

President Theodore Roosevelt addressed Howard’s 1906 graduating class during its 39th annual commencement exercises, which were held at the First Congregational Church in Washington, D.C. Howard has a special relationship with that church; General Oliver Howard and other members were largely responsible for founding the university. Roosevelt spoke about the need for both high ideals and realistically achievable goals, as well as the need for graduates to lift up others after they achieved success.

"We must insist upon high ideals,” said Roosevelt. “If there is not such a high standard set before us then, indeed, will our fall be miserable. We are never going to come quite up to the standard, and it is necessary that the standard should be raised aloft. My plea is that it should not be raised so far aloft as to make us feel the minute that we come to apply ourselves practically that there is not any use of striving after it at all.”

The 27th United States president, William Taft, came to Howard’s campus in May 1909 to speak at Howard’s commencement ceremonies and to commemorate the laying of the cornerstone of the then-new Carnegie Library. Taft spoke candidly about Howard’s inextricable role in fulfilling America’s obligations to its citizens of color.

“This institution here is the partial repayment of a debt — only partial — to a race to which a government and the people of the United States are eternally indebted,” said Taft. “They brought that race into this country against its will. They planted it here irretrievably. They first put it in bondage and then they kept it in the ignorance that that bondage seemed to make necessary, under the system then in vogue. Then they freed it and put upon it the responsibilities of citizenship. Now, some sort of obligation follows that chain of facts with reference to the people who are responsible for what that government did.”

Taft spoke extensively about how educated Black Americans would be critical to enhancing prosperity for members of the race. He argued that Blacks would be instrumental in uplifting their communities and the nation as a whole, and promised to be an active participant in supporting the institution and its mission.

“Everything that I can do as the Executive in the way of helping along this University I expect to do,” he continued. “I expect to do it because I believe it is a debt of the people of the United States, it is an obligation of the government of the United States, and it is money constitutionally applied to that which shall work out in the end the solution of one of the great problems that God has put upon the people of the United States.”

President Calvin Coolidge used his State of the Union speech in 1923 to advocate for a major Congressional appropriation to help Howard train Black doctors. On June 6 of the next year, he came to Howard to deliver the Commencement address. He attempted to salute the progress of Blacks after freedom from slavery, pointing to a dramatic increase in Black wealth over 50 years, the embrace of education by Black people, and Howard’s legendary place in American history.

“The progress of the colored people on this continent is one of the marvels of modern history,” Coolidge said. “We are perhaps even yet too near to this phenomenon to be able fully to appreciate its significance. That can be impressed on us only as we study and contrast the rapid advancement of the colored people in America with the slow and painful upward movement of humanity as a whole throughout the long human story.

“It has come to be a legend, and I believe with more foundation of fact than most legends, that Howard University was the outgrowth of the inspiration of a prayer meeting. I hope it is true, and I shall choose to believe it, for it makes of this scene and this occasion a new testimony that prayers are answered. Here has been established a great university, a sort of educational laboratory for the production of intellectual and spiritual leadership among a people whose history, if you will examine it as it deserves, is one of the striking evidences of a soundness of our civilization.”

In particular, Coolidge used the occasion to pay tribute to Black people who had served in the military, pointing out that those servicemen and women proved that patriotism knows no skin color. He noted that they served with excellence and distinction in World War I on par with members of any other race.

“The nation has need of all that can be contributed to it through the best efforts of all its citizens,” he said. “The colored people have repeatedly proved their devotion to the high ideals of our country. The propaganda of prejudice and hatred which sought to keep the colored men from supporting the national cause completely failed. The black man showed himself the same kind of citizen, moved by the same kind of patriotism, as the white man. They came home with many decorations and their conduct repeatedly won high commendation from both American and European commanders.”

In the midst of the Great Depression, President Herbert Hoover spoke during Howard’s Commencement in 1932. He said that the government’s commitment to Howard is the greatest example of it meeting its obligation to its citizens, and that the talents of all of Americans were needed to protect the democracy.

“The Negro race comprises 10 percent of our population, and unless this 10 percent is developed proportionately with the rest of the population, it cannot pull its proper strength at the oars of our pressing problems of democracy,” Hoover said. “To provide this development requires trained leadership, and I conceive that to be the function of Howard University. You are providing here professional training in all those fields to which the community naturally looks for leadership — religion, law, medicine, education, science, art. You are providing this professional training to men and women of the colored race, to your own best talents, your own leaders by natural endowment. Through the instruction which they receive here, your natural leaders become trained leaders, and this training is of the same kinds and of equal efficiency with that which is provided for the natural leaders of the white race. By this process, the colored people are being integrated fully into the broad stream of the national life, sharing in the obligation and opportunity for political service, for economic advancement, for educational development of the individual, and for enjoyment of all the benefits of science and art and general culture, including skilled medical service, more beautiful home surroundings, and a share in the intellectual progress of mankind.”

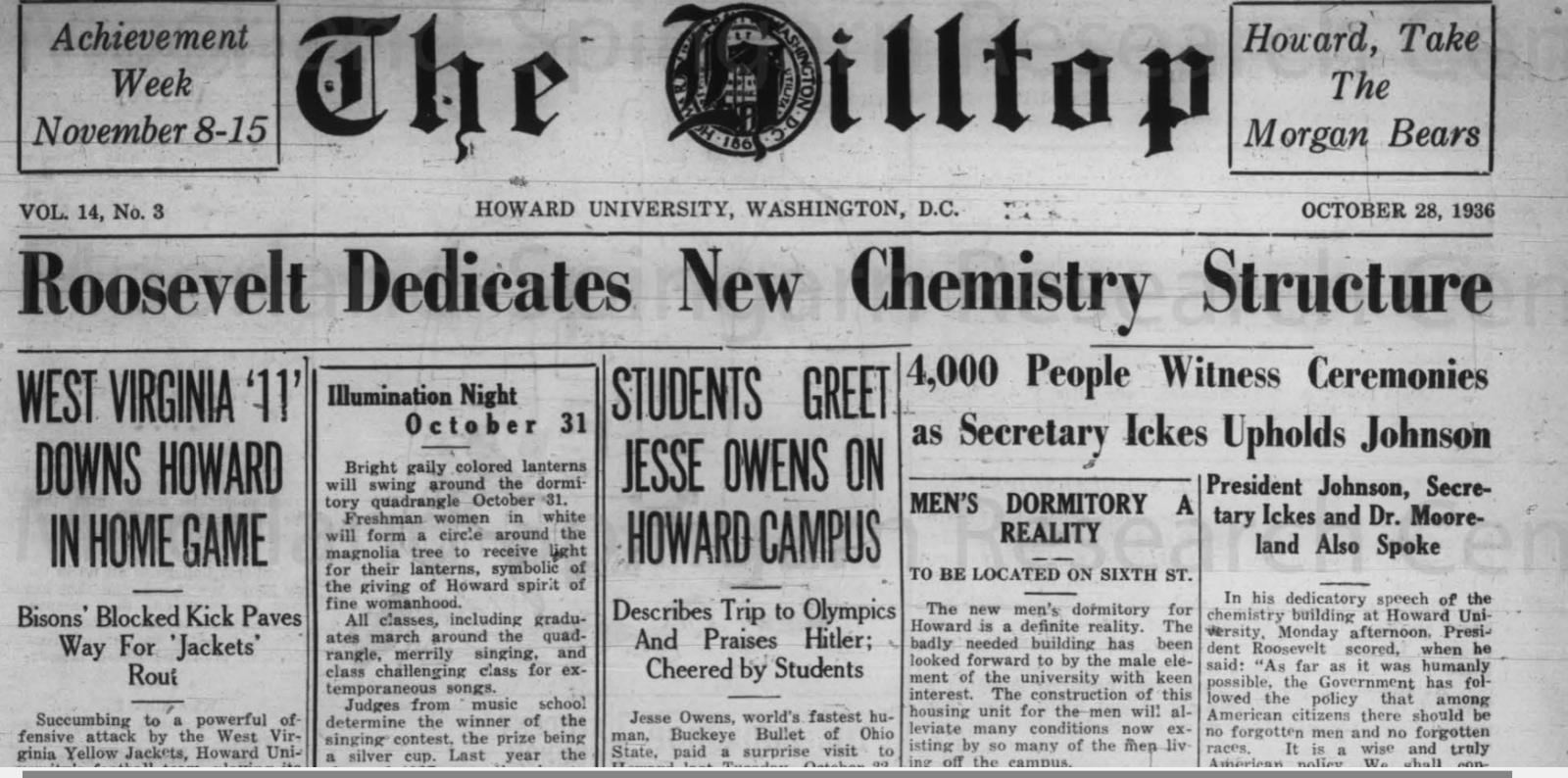

On October 26, 1936 , President Franklin Delano Roosevelt addressed some 4,000 members of the Howard community, talking about the federal government’s relationship with Howard and the importance of its annual congressional appropriation. He also said that Howard would be a symbol for opportunity in America even without its congressional ties.

“I would be interested in this university even though the government had no such relationship,” Roosevelt said. “Its foundation as an institution for the American Negro was a significant occasion. It typified America’s faith in the ability of man to respond to opportunity regardless of race or creed, or color.”

Roosevelt was on campus to dedicate the Chemistry Building, Thirkfield Hall. The architect of many Depression-era public works projects, Roosevelt pointed out the government-financed improvements to facilities at Howard. He issued a call for youth to come to Howard to pursue the advancement of science.

“We dedicate this new chemistry building, this temple of science, to industrious and ambitious youth,” Roosevelt said. “May they come here, to learn the lessons of science and to carry the benefits of science to their fellow men.”

The next president, Harry S. Truman, also spoke during Commencement, addressing graduates during the June 13, 1952 ceremony. He made a case for civil rights advocacy, calling on the nation to do the hard work of addressing injustice and human suffering even if it meant “rocking the boat.” He pointed to Howard as an example of what was possible when people were given an opportunity to excel and singled out the contributions of Howard professor and Chief of Surgery Charles Drew, M.D., who developed the blood bank techniques which saved the lives of countless people around the world during World War II, during the end of which Truman served as president.

“This institution was founded in 1867 to give meaning to the principles of freedom, and to make them work,” Truman said. “The founders of this university had a great vision. They knew that the slaves who had been set free needed a center of learning and higher education. They could foresee that many of the freedmen, if they were given a chance, would take their places among the most gifted and honored American citizens. And that is what has happened. The long list of distinguished Howard alumni proves that the wisdom of those who established this university was profoundly true. This university has been a true institution of higher learning which has helped to enrich American life with the talents of a gifted people. For example, every soldier and every civilian who receives the lifesaving gift of a transfusion from a blood bank can be grateful to this university. For this was the work of a distinguished Howard University professor, the late Dr. Charles Drew, that made possible the very first blood bank in the whole world.

“This is a practical illustration of the fact that talent and genius have no boundaries of race, or nationality, or creed. The United States needs the imagination, the energy, and the skills of every single one of its citizens. Howard University has recognized this from the beginning. It has accepted among its students, faculty, and trustees, representatives of every race, every creed, and every nationality.”

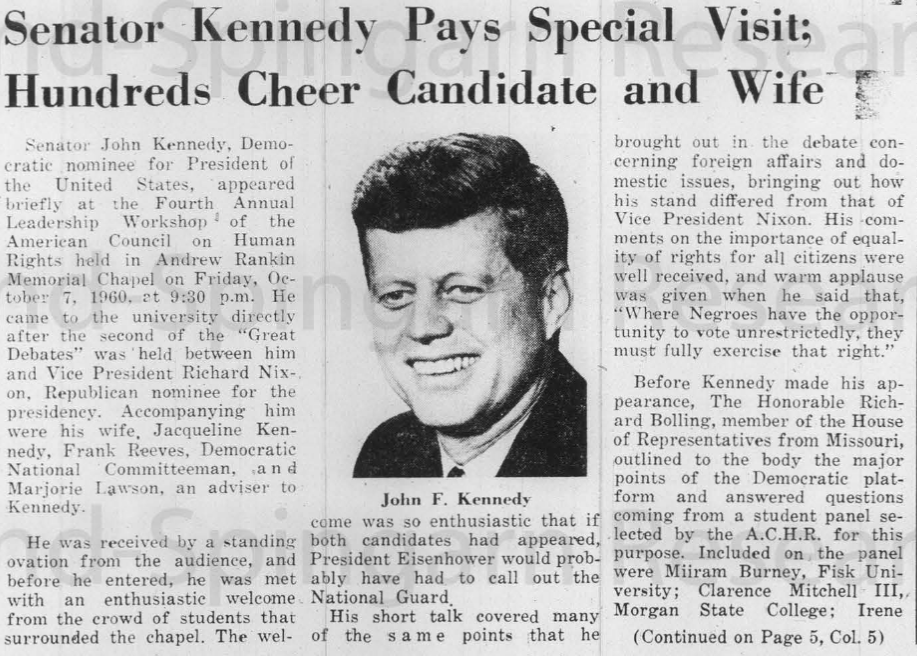

On Aug. 4,1956, as vice president of the United States, Richard Nixon led a panel discussion at Howard University School of Law, engaging in a discussion with then-dean George Johnson, attorney Rufus King, and Judge Leonard Walsh, among others. Nixon would become president in 1969. During the pivotal 1960 presidential campaign, then-, U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy spoke on Howard’s campus in the historic Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel during the Fourth Annual Leadership Workshop of the American Council on Human Rights. Accompanied by his wife Jacqueline Kennedy, the senator came to campus after also participating that night in a nationally televised presidential debate in his famous series against Nixon. The Democratic party was attempting to attract Black voters who had historically voted for Republicans, the “party of Lincoln.” He made the case that the Democratic party was committed to human rights around the world and to meeting problems in new ways. As the Cold War heated up, Kennedy said that equal opportunity was critical to American competitiveness against adversaries like the Soviet Union. Kennedy was elected president in 1960.

“I believe in equality in opportunity of employment which is extremely important and then I believe we have to improve our educational standards for all children, regardless of color, all children, white and Negro,” said Kennedy. “We are producing about half as many scientists and engineers as the Soviet Union.

“If we attempt to patch up those areas in our national life where equality of opportunity is not provided, if we give force and vigor to the concept of that equality, if we sustain it with laws, if we sustain it by executive action, if we sustain it by moral force and if we lift the economy of the whole and all Americans, then I believe we will be meeting our responsibility to the 1960s.”

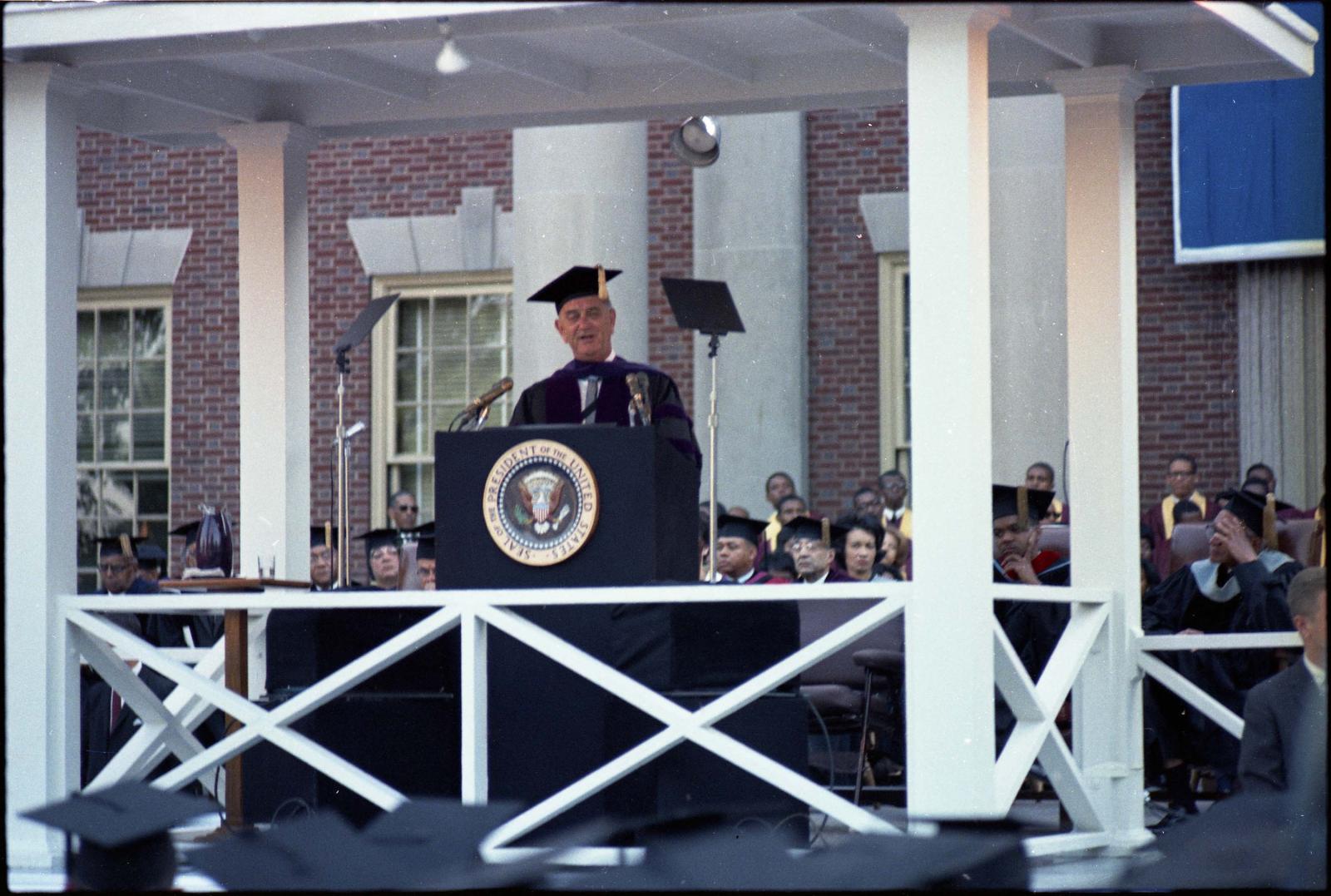

On June 4, 1965, President Lyndon Baines Johnson delivered important remarks on civil rights as part of his Commencement address on campus a few months before the passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act. Johnson used the occasion to urge the passage of the law, which provides for federal government action to ensure that every American has the right to vote. He also called for action to reduce the unemployment rate and raise incomes for Black workers, lower Black infant mortality rates, expand access to education, improve medical care, provide job and skill training and reduce poverty. During the remarks, he announced his plans to host a White House conference of scholars, experts, and Black leaders to help solve problems related to injustice. He acknowledged that while the American concept of freedom and equality was an ideal, it was far from a reality.