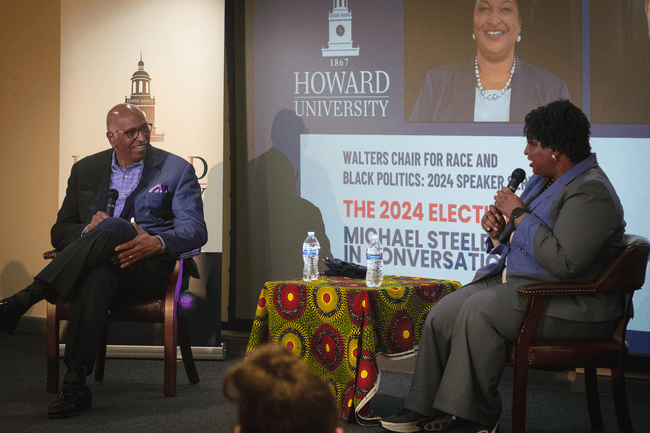

How intense were the fireworks, thinly veiled insults, unfounded accusations, and appeals to the extreme wings of their parties when Michael Steele, the former chairman of the Republican National Committee (RNC), and a Stacey Abrams, two-time Democratic party nominee for governor of Georgia, met to talk about the state of the 2024 election?

Actually, there were none. And that was the point.

Steele, Howard University’s King Endowed Chair for Public Policy, joined Abrams, the University’s Walters Endowed Chair for Race and Black Politics, to discuss their careers and what’s at stake ahead of the 2024 election. The discussion was wide-ranging, and Abrams and Steele identified guideposts for modern-day politics. The two are political heavyweights, both of whom made history: Steele as the first Black RNC chair, and Abrams as the first Black Georgia gubernatorial nominee.

The event was a master class in civil political conversation. Here are some takeaways from the dialogue between the trailblazing politicians.

Shut Up and Listen

Steele and Abrams found common ground in their background as minorities—not only racial minorities, but as members of the minority political party in their respective states. Steele, who grew up in DC’s Petworth neighborhood, recalled his first experiences campaigning for Republicans in the area. Many doors were closed in his face. But, he said it showed him the importance of conversation and the requirement of listening, values he learned from his late mother.

“She taught me how to shut up and listen,” he said. “And that has worked well for me in a lot of my political engagement.”

Steele eventually became the Republican county chairman in Prince George’s County. Even though Republicans were severely outnumbered, he was able to lead the party in conversations with voters about property taxes and government overreach. The result, he said, was that his party was able to win significant legislative battles at the county level.

“It’s how you apply yourself to the work despite the obstacles and how you engage the conversation when others aren’t necessarily willing to listen and have [already] decided how you are going to come at them,” said Steele.

Don’t Let Your Relationships Be Defined by Your Party Affiliation

Steele has never shied away from building relationships on the opposite side of the political aisle. A little-known aspect of Steele’s political ascension was his mentorship by DC’s “mayor for life” Marion Barry, then one of the nation’s most prominent Democrats. Barry also advised Steele during Steele’s 2006 campaign for U.S. senator.

From Barry, Steele learned that it was critical to care more about the people who put you in office than raw politics. He said that Barry’s commitment to underserved areas of the city was the reason DC voters supported the mayor politically even after he ran into personal and legal trouble later in his career.

“When you sat and talked with him, he would always say that your focus as an elected official has to be on the people you serve, because the moment it becomes about you and what you want and your vision, then you are no longer serving,” Steele recalled.

That sentiment guided Steele’s term as Maryland lieutenant governor, the first time a Black person ever held statewide elected office in the state. During his inauguration, he looked out over the crowd to the nearby harbor and reflected on the irony that he was looking at the place where slaves like Alex Haley’s ancestor Kunta Kinte were brought to the country in chains. He realized that he wasn’t the lieutenant governor for just Republicans in Maryland, but rather a leader for the everyone in the state.

Turn Down the Heat

Abrams reflected on her election as the first woman to lead a political party in the Georgia House of Representatives, when the state’s Democratic party was undergoing a radical transition. An uneasy alliance of “Dixiecrats,” civil rights leaders, and new arrivals to Georgia from northern states was beginning to fracture, and Democrats soon lost every statewide office in addition to their majorities in both chambers of the Georgia legislature.

She wanted to change how people viewed the Democratic party in the state, but she couldn’t do it if she spent all her time being angry. That put her at odds with members of her party who expected her to be “righteously indignant.”

Abrams had three rules. First, she was determined to cooperate where she could, especially in helping to make bad legislation better. Second, she focused on presenting a competing vision of public policy that stood in contrast to that of the Republicans. Finally, she worked to ensure that elected officials were accountable to their constituents.

“It wasn’t enough to say they were wrong,” she said. “We had to say why we were right, but you can’t do that when all people hear is screaming.”

Meet People Where They Are, Not Where You Want Them to Be

Abrams believes that much of her success in Georgia was due to her willingness to show up in places her party did not often visit. There, they were able to have conversations that led to collaboration and organization. The key, she said, is to be consistent and authentic in your engagement and to ask them what they need, want, or fear. Above all, she said, just show up, and then show up again.

“Showing up in places where people don’t expect to see you lets them know that you can see them,” Abrams said. “The first time you show up is novel. The second time you show up is commitment. When you are organizing, people don’t need to know that you want them. People want to know that you need them.”