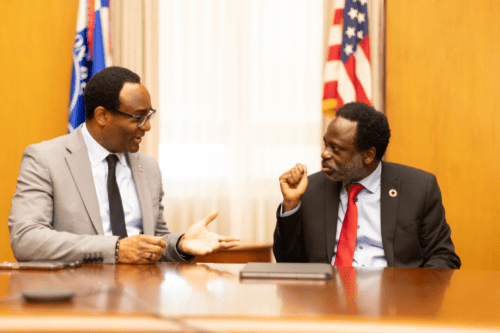

Photos courtesy Jake Belcher, MIT

MIT's Spring 2025 Karl Taylor Compton Lecture Series by Howard University President Ben Vinson III. Video courtesy of MIT.

After electricity was harnessed or the printing press was industrialized, what if they were restricted only to certain groups, classes, nationalities, or races of people? What would that have meant for human progress, and for the rights of all members of the human race to thrive? As artificial intelligence continues its march toward becoming a dominant technology integrated into virtually every aspect of human life, similar questions are being raised. Can humanity and AI coexist without irrevocably diminishing what it means to be human?

Howard University President Ben Vinson III, Ph.D., who has invested time and scholarship into examining this issue, delivered an illuminating lecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as part of its Compton Lecture Series. His presentation was titled “AI In an Age After Reason: A Discourse on Fundamental Human Questions.” Much of his discussion was framed around the fundamental questions that humanity needs to ask.

“I want you to remember just how intimately connected our present, and even our future, is with our past, and previous so-called ‘ages,’ and some of the issues about humanity that emerged in them,” he said.

Vinson opened his remarks by discussing how the human capacity to reason has been mitigated by societal constructs. He referenced time periods in history when science and the power of intellect were heralded as a liberating force and a way to demonstrate the progress of humanity. In many cases where something valuable is uncovered, some people saw intellect as the exclusive province of a small number of people.

“The forces of our intellect were viewed as liberating us from older, primordial habits, worldviews, and thought processes that supposedly kneecapped human development,” said Vinson. “At the same time though, in the Age of Reason, the full power of intellect was hoarded by a select few. The true ability to reason was not believed to be available and achievable for all.”

That sentiment — that certain people were not physically capable of reason — served as the basis for any number of human-on-human atrocities. It enabled the powerful to put people into certain castes of second-, third-, and fourth-class personhood. If one’s mind wasn’t developed enough to reason, it was argued, then they weren’t fully human, and therefore didn’t have to be treated as one. Vinson posited that similar risks of dehumanization exists with the rise of AI.

Reasoning over time has not just served to define what is human, and what it means to be human, but who could be fully human."

“Reasoning over time has not just served to define what is human, and what it means to be human, but who could be fully human,” Vinson continued. “In some ways this question still lingers, as cultures still jostle with differences of perceived intelligence that justify subordination, creating hierarchies of human life.”

Machine computing has historically been relegated to increasingly sophisticated execution of commands that have been directed by human beings, though many computing systems have been automated and have grown to a scale hard to fathom, except by technological geniuses. Nevertheless, no matter how complex, the computing systems have not been able to “think” for themselves and have existed to carry out the will of their programmers. AI, by contrast, is technology through which a computational system can mirror human intelligence and learn, make decisions, problem solve, and generate perspectives. Instead of performing tasks based on a set of instructions provided by humans, artificially intelligent machines can make decisions for themselves. Given the power, speed, and virtual omnipresence of computing networks, AI has the power to transform the planet benevolently, while it simultaneously poses existential threats to our way of life. It isn’t a stretch to predict that the future will depend on how we collectively govern the evolution of AI.

Given humanity’s struggle with the concept of basic human reasoning, Vinson questioned a future where yet a new stratum of perceived intelligence exists in the form of computational reasoning.

“If it reasons, are we moving toward an age after human reason?” questioned Vinson. “And what might that mean for the fundamentally human questions of our humanity?”

Vinson’s perspectives on the issue come in part from the multiple lenses through which he sees the past, present, and future as a scholar and a university president. He leads the historically Black college or university that is significantly focused on steering AI research and application. Howard is the institutional lead of the Research Institute for Tactical Autonomy (RITA), the first University Affiliated Research Center funded by the U.S. Air Force. To support U.S. military missions, RITA is conducting research into autonomous technologies that function with minimal human supervision in complex and unpredictable environments in the air, in space, in cyberspace, on the ground, and in the sea. At the same time, the university has partnered with OpenAI to use AI in teaching, to enhance administrative effectiveness, and to upscale global access to the university’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, “the largest and most comprehensive repository of books, documents, and ephemera on the Black experience.” Vinson argued that HBCUs are uniquely positioned to help ensure that AI serves humanity, not the other way around.

“We have an obligation to ensure that AI is shaped by diverse voices, not by historical biases encoded into algorithms,” he said.

Vinson is also a noted historian who has conducted significant research on Latin America and the African diaspora. He served as chairman of the National Humanities Center, is a board member of the National Humanities Alliance, and currently serves as president of the American Historical Association. His book, “Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico,” won the 2019 Howard F. Cline Book Prize in Mexican History.

“I confess that I believe that artificial intelligence is not merely a technological advancement; it is potentially a force reshaping the very foundations of society, humanity, and the academic institutions we represent,” he said. “I also confess that as leaders in education and research, universities, and all of us in them, have a critical role to play in addressing the philosophical, ethical, and existential questions AI presents.”

Vinson believes that the field of humanities can provide invaluable context as we navigate this moment. At MIT, he raised concern that the growing emphasis on AI may, ironically, devalue study in the humanities, a field he argues is critically important in examining the very philosophical and ethical implications of technological progress like AI.

“Can AI and the humanities truly coexist, or are we witnessing a reconfiguration of human knowledge itself?” Vinson asked. “AI’s rise in our everyday world forces us to ask what kind of future we are constructing. Does a world with diminished emphasis on the humanities signal a new evolutionary stage of humanness — one in which our narratives, histories, and philosophies are increasingly mediated, perhaps even rewritten, by intelligent machines?”

His speech called for a sober and thoughtful approach as the ramifications of AI are considered. According to Vinson, all technological breakthroughs carry with them both positive and negative perceptions. It is the role of academia, he said, to sort it out.

“AI will likely evolve through a cycle of inflated expectations, disillusionment, and eventual pragmatic integration,” he said. “This is why universities must serve as the intellectual compass in this transformation — separating real risks from speculative fears, ensuring AI is neither demonized nor blindly embraced, but developed with wisdom, ethical oversight, and societal adaptation.”

Vinson’s line of questioning wove a thread through both fundamentally practical concerns and more theoretical interrogatives questioning whether the use of the term “intelligence” is appropriate in the first place, especially when it comes to machines. He also questioned whether machines could be trusted to make decisions regarding history and culture without injecting bias that can harm swaths of people.

Vinson’s questions will ultimately need answers. He proposed a set of guideposts around which to navigate the conversation. Those guideposts would help mark directions in morality, privacy, technological weaponization, and geopolitics. Much of this work, he insisted, can be done through academic inquiry, research, and public discourse.

"Intelligence — whether human or artificial — does not exist in isolation."

Vinson called upon academia to use an interdisciplinary approach to advance ethical AI development and ensure its alignment with human values and social justice. As educational institutions integrate AI into educational and workforce preparation programs, Vinson wants students to understand AI’s broad societal implications, as well as how to use creativity, adaptability, and emotional intelligence to navigate the dynamically changing technological landscape. He also believes that colleges and universities can be a driving force behind using AI to promote global equity and sustainability.

“Intelligence — whether human or artificial — does not exist in isolation,” Vinson said. “It is embedded in relationships, histories, ecosystems, and cultures that shape how knowledge is produced, shared, and applied. If we are to develop AI that truly serves all of humanity, we must broaden our analytical canvas, drawing on diverse intellectual traditions that have long engaged with questions of knowledge, agency, and interdependence.”

Keep Exploring

United Nations Undersecretary-General and Howard President Meet to Discuss Global Education

Howard President Ben Vinson III, Ph.D., Shares How Colleges Can Help Solve Housing Problems

Keep Reading

-

Vanguard

VanguardHoward University Gallery of Art Lends Elizabeth Catlett Works to Major Exhibition on Black Women’s Historical Memory

Jan 30, 2026 3 minutes -

Legacy

LegacyBuilding the Mathematical Mecca: Howard’s Half‑Century of Innovation, Scholarship, and Leadership

Jan 29, 2026 7 minutes -

Find More Stories Like This

Are You a Member of the Media?

Our public relations team can connect you with faculty experts and answer questions about Howard University news and events.

Submit a Media Inquiry