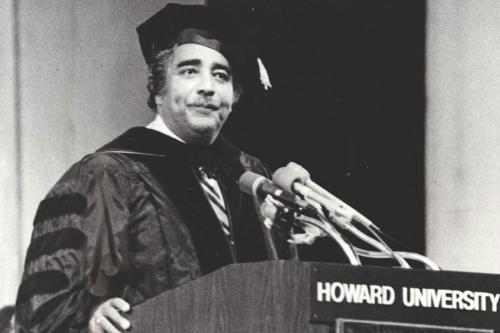

WASHINGTON –Howard University School of Law celebrates the life and legacy of its distinguished alumnus, Federal Judge Damon Keith (J.D. ’49), who died Sunday at 96. The law school sends condolences to his family, friends, and law clerks.

WASHINGTON –Howard University School of Law celebrates the life and legacy of its distinguished alumnus, Federal Judge Damon Keith (J.D. ’49), who died Sunday at 96. The law school sends condolences to his family, friends, and law clerks.

Keith was born on July 4, 1922 in Detroit, Michigan. After earning his bachelor’s degree from West Virginia State College (1943), serving in a segregated Army in World War II, Keith enrolled at Howard University School of Law. Working with mentors such as Thurgood Marshall and Spotswood Robinson III, Keith graduated from Howard Law with the praise of his revered instructors, which he claims was “the proudest moment in his academic life.”

In October 2017, Keith celebrated 50 years on the federal bench, where he served as a judge for the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan (1967-1977) and for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (1977-2019). He believed strongly in the words etched on the front of the U.S. Supreme Court – “equal justice under law” – and his judicial opinions demonstrate his conviction.

During his tenure on the district court, he delivered several landmark rulings in civil rights case advancing equality for everyone in Michigan: on school desegregation in Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, Inc. (1970); on employment discrimination in Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co. (1973); and on housing discrimination in Garrett v. City of Hamtramck (1971), a case which was still being litigated nearly 50 years later. Although these decisions were controversial and Keith received hate mail from people spewing racial hatred, he did not let that stop him from deciding cases in the manner he believed was right.

A firm believer in an open and transparent democracy, Keith is most known for his district court opinion in United States v. Sinclair (1971). In Sinclair—referred to as the "Keith decision”—he upheld the Fourth Amendment, finding that then-President Richard Nixon and then-Attorney General John Mitchell could not engage in warrantless wiretap surveillance of three individuals suspected of conspiring to destroy government property.

“Judge Damon Keith was a legend and a pioneering figure in the legal profession,” said Danielle Holley-Walker, dean, Howard University School of Law. “He will leave an enduring legacy through his jurisprudence and his mentorship of his law clerks.”

One such former law clerk of Keith’s is Claude E. Bailey (J.D. ’83), partner, Venable LLP, who can certainly attest to this notion.

“He was one of the first and the few Black federal judges who was very intentional about hiring Black law clerks, including students from Howard Law,” Bailey said. “He considered his law clerks as part of his family. He kept lifelong relationships with all of his clerks and would check on us to see how we were doing, both professionally and personally.”

One quote Bailey will never forget Keith saying to him are these words: “We are walking on floors we did not scrub and walking through doors we did not open.”

Keith paid his last visit to Howard Law in September 2016, when the law school hosted a showing of the U.S. Courts Moments in History video, released in celebration of Black History Month. WATCH here: https://bit.ly/2XXJcfv

“Howard Law will celebrate and lift up Judge Keith’s critical work as we continue to work to transform the law to recognize the fundamental humanity of all people in the United States and around the world,” Holley-Walker said.

At least two Howard Law professors, Justin Hansford and Robin Konrad, served as Keith’s clerk in their earlier profession. Here’s what they had to say about their time working under the legend that was Keith.

Justin Hansford, associate professor of law and director of the Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center:

I served as Judge Keith’s clerk during the 2009-10 term. We became close during that time and remained so over the years.

He forever altered the trajectory of my career by adding me to his illustrious professional network. But more importantly, he forever altered the trajectory of my life by inspiring me to be the best person I could become. I love him dearly.

In the legal profession, he already was a NAACP Spingarn award winner in the 1970s, beloved for his leadership in the NAACP and his aggressive civil rights rulings on affirmative action, housing discrimination, women’s rights, and more. He gained a type of “crossover appeal” with his rulings on civil liberties, establishing the law against presidential wiretapping. This endeared him to adherents of civil liberties and separation of powers, later ruling against secret interrogations in the war on terror, gaining admiration from supporters of the First Amendment, media rights, and people who support human rights and who have fought against abuses that took place during the war on terror. As a result, white, Black, Jewish, Muslim, Christian, rich, poor, and everything in between—they all adored him, because he represented the best of all of us.

One of my favorite memories is how he fought to raise, I believe, over a million dollars in the span of a couple of days to save the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit, one of the nation’s most beloved African American history museums. He had relationships with powerful people and millionaires, whom he regularly leveraged to help for worthy causes.

Among African American lawyers and judges, he is royalty –not only because of his accomplishments, but because of his warmth, generosity, and eagerness to serve. He had a unique spirit that both commanded utmost respect and also was generous and warm enough to inspire great affection.

Robin Konrad, assistant professor of lawyering skills:

Below is an excerpt (with minor edits) authored by Prof. Konrad for a chapter she wrote in the book, Of Courtiers and Princes: Stories of Lower Court Clerks and Their Judges, by Prof. Todd Peppers (publication forthcoming Feb. 2020).

Judge Keith was a person who epitomizes the cliché “practice what you preach.” I came to learn this at an event where he shared a story about hiring me. We were at a luncheon in which Judge Keith was honored by the Wolverine Bar Association, an organization established in the 1930s to address the exclusion of African-American attorneys in bar associations across the state of Michigan. As part of the ceremony, Judge Keith presented a keynote speech. At times, his law clerks would help him draft his speeches. But during this event, Judge Keith went off-script and told a story that I had never heard. He began by stressing the importance of equal justice under law—a guiding motto in his life—and of ensuring that society did not judge people based on the color of their skin. Judge Keith’s entire life and career is a testament to these principles, and I had heard him tell stories underscoring the importance of these values many times in the past. But this time, he shared a personal example in which he used his own words to guide a decision he made: to hire me.

When Judge Keith saw my résumé, he said that he was sold. Not only had I graduated at the top of my class from Howard University School of Law, but I had also served as Editor-in-Chief of the school’s law review. I had demonstrated a commitment to social justice by my work with Amnesty International, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Human Rights Campaign. During my third year of law school, I was one of a small group of students who drafted an amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court in support of the University of Michigan School of Law in its desire to use race as one of many factors considered in admissions to ensure a diverse institution. After reading my background, Judge Keith assumed that because I attended a historically Black university, that I, too, was Black. But I am white.

During the luncheon, Judge Keith told the audience that he was taken aback by the assumptions he made regarding my identity. Judge Keith was committed to ensuring diversity among his clerks and ensuring that people who have not historically had access to federal clerkships would be given a fair opportunity to work with him. When I applied, Judge Keith had multiple qualified applicants from different racial backgrounds, and he questioned who was best for the position. He had already filled the other two positions—one clerk was a Black man; the other clerk was a white woman. As Judge Keith was telling this story, my face began to turn from pale cream to a bright red. He then told the Wolverine Bar Association that he prayed, seeking guidance on what to do. (At this point, my face had to have been brighter than the strawberries we ate for lunch!) Judge Keith explained that if he did not hire me simply because of my skin color, then he would be acting in the same way that people in power have acted for centuries. Because he wanted to practice what he preached, Judge Keith offered me the position.

I’m not going to lie. Hearing that story made me feel a little embarrassed at the time. But over the years, in thinking about the systemic oppression and discrimination that Judge Keith faced as a black man in America, I have come to recognize, honor, and value the courage that he demonstrated each and every day by his actions. Indeed, knowing Judge Keith and being part of his clerk family has helped me in finding the strength to live by principles of fairness and to do what is right even when it’s unpopular.