While Howard University is recognized as historically Black, founded for African-Americans in a post-slavery United States, many of its founders were white abolitionists sympathetic to this newly freed people’s need for a proper education.

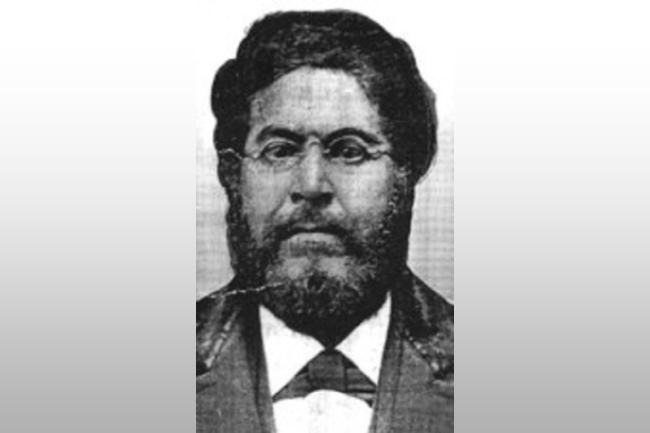

Among these founders stood George Boyer Vashon, an African-American attorney, scholar, and poet who would support the University’s opening in 1867, becoming Howard’s first Black professor and playing an essential part in establishing the Howard University School of Law.

By the time of Howard’s chartering, Vashon had amassed a list of accomplishments that would be impressive at any moment in American history. Yet his genius would not be insulated from his race and the more prejudicial policies of the era.

Born in Pennsylvania to an abolitionist father, Vashon was a high achiever from an early age, matriculating to Oberlin College in Ohio at 16 and becoming the first African American to graduate from the institution in 1844. Vashon was also class valedictorian.

Vashon understood the power of education in liberating the race and used his position at Oberlin to enroll more Black students at the college, says his great-great grandson and family historian Paul Thornell.

“He had a pretty critical role in bringing a number of Blacks who were in the area around Oberlin, among them John Mercer Langston, who was elected to Congress,” Thornell says. “He had a strong commitment in helping bring in younger Blacks to whatever educational institution he worked with.”

After Oberlin, Vashon apprenticed under Walter Forward, a Pittsburgh-area judge and former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, in preparation for Pennsylvania’s bar examination. Despite his impressive credentials, Vashon was denied admission because of his “Negro descent,” a setback Thornell posits was disheartening, even embarrassing, for his great-great grandfather.

“When it came down to it, he was treated just like any other Black person who had not gone to college, who had not studied with a former treasury secretary and sitting judge, who had not done anything,” Thornell says. “I’m confident a big part of where his mind went after it was, ‘There’s really no hope for me in this country.’”

Vashon would subsequently depart the Pennsylvania region; he first stopped in New York, passing their bar examination in 1848 and becoming the first-ever Black lawyer in the state, before decamping for Haiti, where he would sojourn for nearly two-and-a-half years as a professor of Latin, Greek, and English. According to Thornell, Vashon, whose middle name is the surname of Haitian Revolution leader Jean-Pierre Boyer, chose the island because of its own recent history.

“A lot of [Black Americans] at the time looked to Haiti as almost this monument to what an organized group of Black people could do, with the Haitian Revolution of 1799,” Thornell says. “It was very much one set of people taking on an imperial power, an example of what was possible.”

Still, with diminishing prospects in Haiti, and a plethora of personal and professional issues to manage domestically, Vashon returned to New York in 1850 where he opened a law practice in Syracuse and took guardianship of his sister’s four children after her death.

In 1854, Vashon joined the faculty at New York Central College, earning just the third professorial post for an African American at any college or university in the nation. One year later, Vashon became the first Black person to seek a New York statewide office in an unsuccessful bid for attorney general. Throughout this time, Vashon was a key player behind-the-scenes, attending national anti-slavery conventions as a corresponding secretary and writing articles for Frederick Douglass’ newspaper “The North Star” under the initials ‘ERN’.

“He obviously didn’t get the notoriety of a Frederick Douglass or Martin Delany or Benjamin Lundy or William Lloyd Garrison, but he was doing the work,” Thornell says. “He may not have been the one reading the speeches, but he was in those rooms writing them.”

Look at how many graduates of the institutions that he was connected with, how many people who descend from slaves that he helped on the Underground Railroad.”

Thornell says that Vashon met General Oliver Otis Howard while working at the Freedmen’s Bureau around 1866, and the two formed a relationship from there. In addition to teaching mathematics and English at Howard, Thornell says Vashon temporarily administered a night school for the University that allowed those with daytime employment to pursue their studies after hours.

“Whether it was certain institutions of education or enterprises that were founded to focus on the interests of Black people, in many cases they were started by whites or had whites as part of the founding, which is an important thing to lift up in our history,” Thornell says. “But, as I’ve understood, he was the first Black professor, and was integral to the founding of [Howard].”

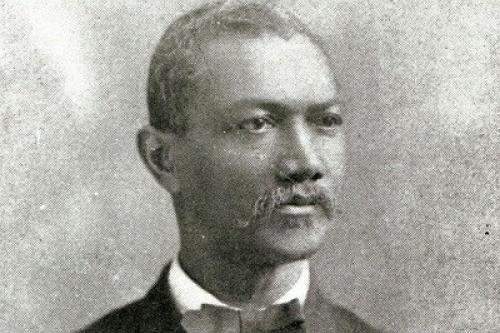

Vashon pursued a variety of positions in the D.C. area while at Howard, but after another string of disappointments, he departed for Mississippi and fellow HBCU Alcorn College (now Alcorn State University). Hiram Revels, the school’s president and the first Black U.S. congressman, personally recruited Vashon to join its faculty. Vashon would ultimately fall victim to the 1878 Mississippi Valley yellow fever epidemic, dying at age 54.

“The multiplicity of what he did is so powerful,” Thornell says. “All of the firsts, all of the extraordinary ways that he excelled, so much what he tried to do was thwarted because of the color of his skin. But he kept going and persisting and contributing.”

“I think if you had to define or quantify how what he did what he did in his life translates into results, it would be an incomplete picture if you just looked in the years that he lived,” Thornell continues. “Look at how many graduates of the institutions that he was connected with, how many people who descend from slaves that he helped on the Underground Railroad. I think there’s no doubt that he was not typical, but in many of ways, his story is also [one] that we’ve seen throughout American history.”

As Vashon’s family prepares to commemorate his 200th birthday this summer at various stops that reflect his life and career, Thornell hopes to recognize the contributions of his revered ancestor at Howard University. In his own day-to-day, Thornell aspires to advance the Vashon legacy in ways that most definitely owe to the University’s core values.

“We reap the benefits every day of what he did, but at least for me, how am I in the course of a day, in the course of my life, continuing to find important ways to move the ball forward?” Thornell asks rhetorically.

“It’s both education and service – I kind of hold those two things together,” Thornell resolves. “It’s the idea of doing service in a way that brings other people along.”