Elizabeth Catlett was more than an artist — she was a revolutionary force in the world of sculpture, drawing, and printmaking. Through bold, expressive forms and socially charged imagery, she captured the strength, resilience, and struggles of Black and working-class people in the United States and Mexico. From her early years at Howard University to her life in political exile, Catlett remained steadfast in her belief that art was not just for galleries, but rather for the people. The National Gallery of Art now features an exhibition called "Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist," slated to be shown through July. On April 5, 2025, the Howard art department will celebrate with activities and open showings of her art in this exhibit's honor.

Early Life and Howard University

Born in Washington, D.C., in 1915, Catlett grew up in a world defined by racial barriers. Despite her talent, she was rejected from the Carnegie Institute of Technology due to her race. At the suggestion of her mother, she enrolled at Howard University.

At Howard, Catlett studied under influential Black artists and scholars, including Loïs Mailou Jones, James A. Porter, and James Lesesne Wells. She embraced a rigorous curriculum that emphasized both artistic technique and the responsibility of Black artists to depict their community’s experiences.

Catlett was a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. She was also the business chair for the Dauber's Art Club. In 1935, she graduated cum laude with a degree in art, carrying with her a commitment to social justice that would define her career.

Breaking Barriers in Art

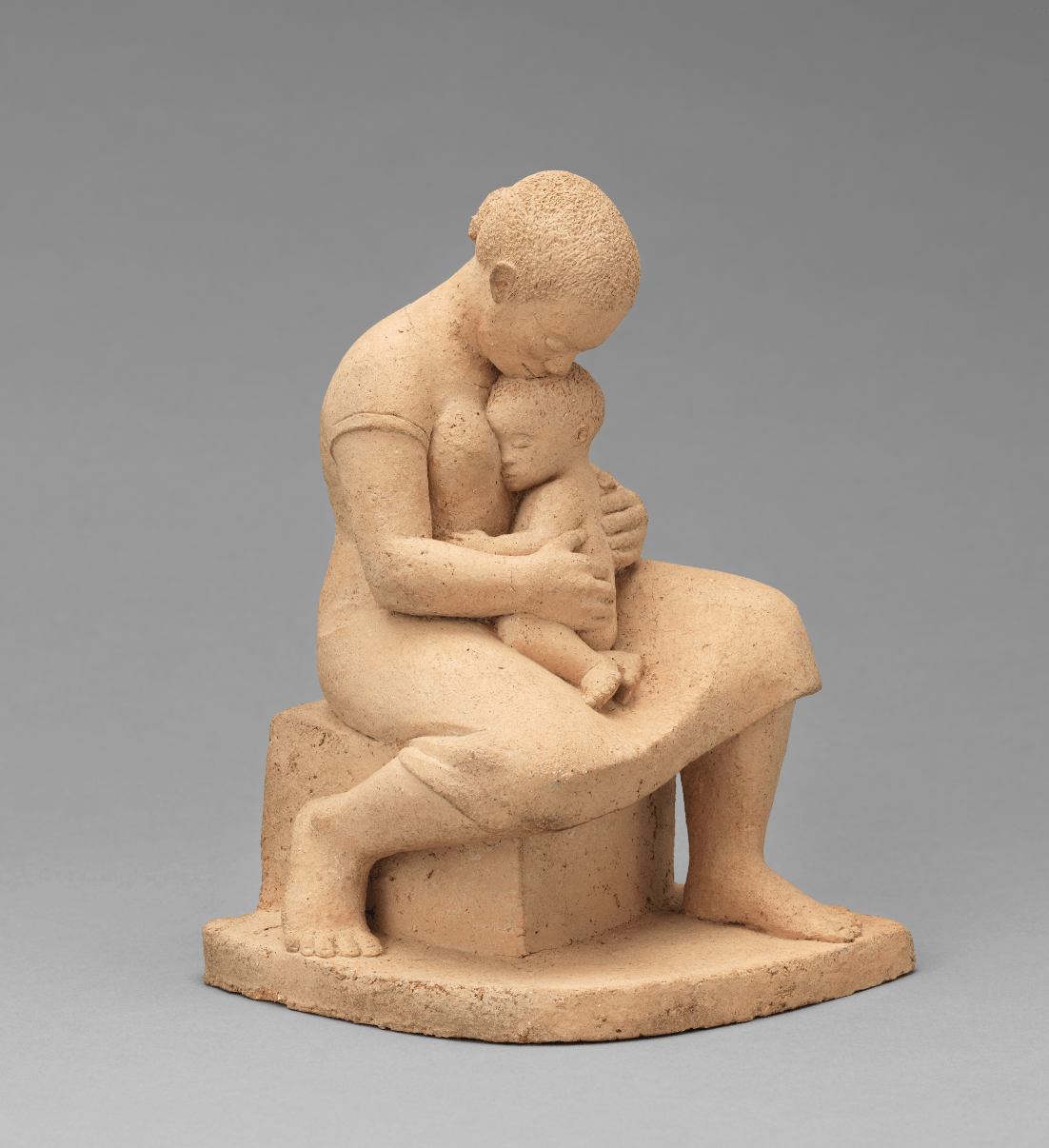

Catlett continued her education at the University of Iowa, where she became the first Black woman to earn an Masters of Fine Arts in sculpture in 1940. Studying under Grant Wood, she was encouraged to focus on subjects from her own heritage. This led to "Negro Mother and Child" (1940), a limestone sculpture that embodied the quiet dignity and resilience of Black motherhood.

“Artist activist work is about continually reminding people of their humanity, and reminding people that we need to pursue humanity in an equal way that gives compassion and justice to all,” said Dr. Melanee Harvey, associate professor, coordinator for art history, and chair of the James A. Porter Colloquium on African American Art at the Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts.

Her early career was marked by obstacles. As a Black woman in the 1940s art world, she struggled to gain recognition, often working multiple teaching jobs to sustain herself. She taught at Dillard University in Louisiana and later at the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago, where she connected with artists like Charles White, whom she later married.

“She wasn’t an artist who worked in just one material — she excelled as a printmaker, as a sculptor, and her work could speak to the masses through an art form that is often considered high art,” said Dr. Gwendolyn H. Everett, interim dean of the Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts.

Activism and Exile in Mexico

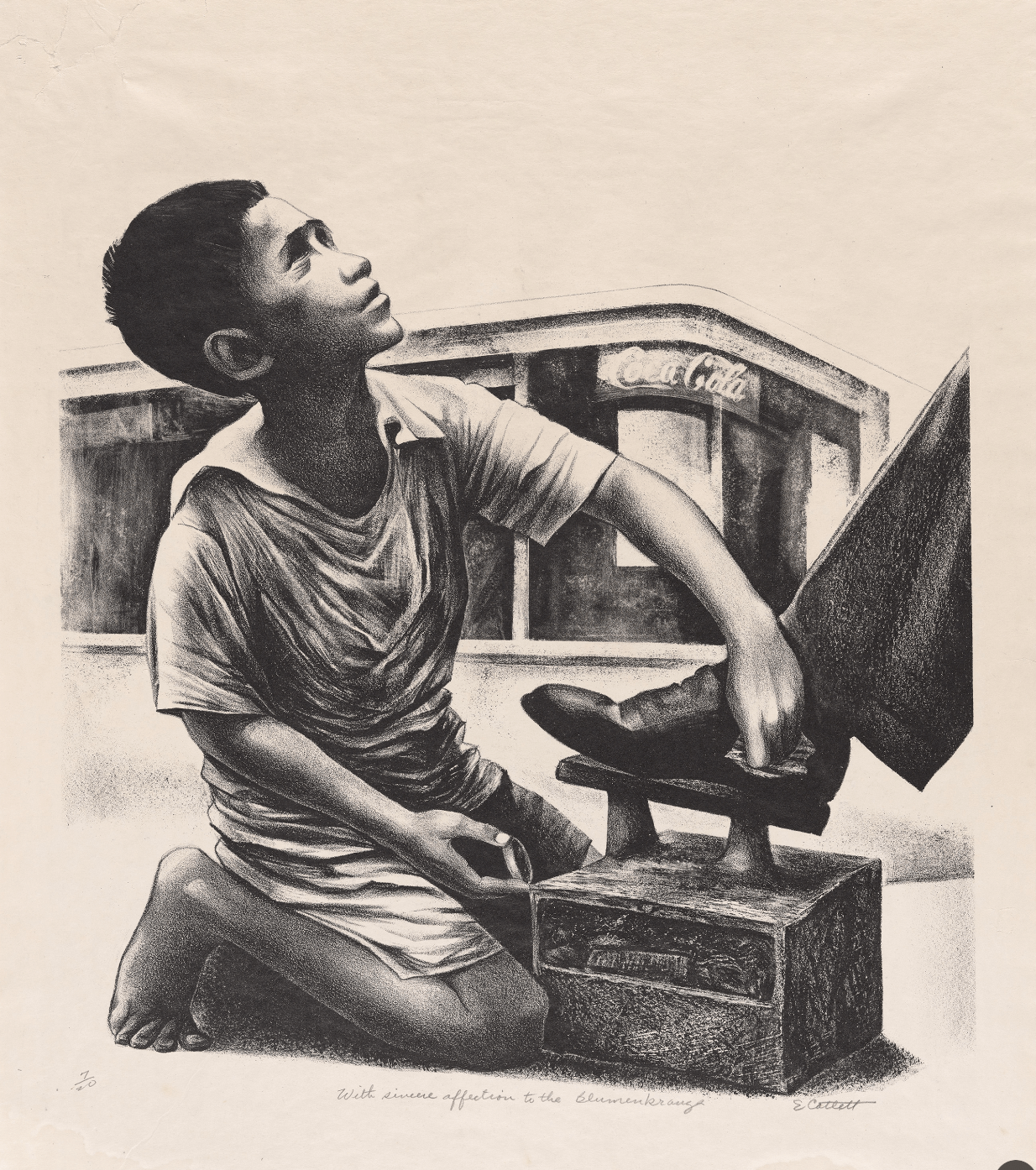

In 1946, Catlett received a prestigious Rosenwald Fellowship, which allowed her to travel to Mexico City. There, she joined the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP), a collective of artists committed to using printmaking for social justice. Her time at TGP shaped her politically and artistically, leading to some of her most famous works, including "Sharecropper"(1952), a linocut that portrays a weathered yet defiant Black woman in a straw hat, embodying the endurance of agricultural workers.

During the McCarthy era, Catlett’s activism drew the attention of the U.S. government, which labeled her a communist sympathizer. In 1959, she was barred from returning to the United States, and in 1962, she renounced her U.S. citizenship to become a Mexican citizen. Despite this forced exile, she continued creating, producing works that uplifted marginalized voices across borders.

A Legacy in Sculpture and Printmaking

Catlett’s art was deeply personal and political. Her "Negro Woman" series (1946-1947) told a visual story of Black women’s struggles and triumphs, featuring figures like Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. The series included pieces such as "I Have Special Reservations" (1946), which depicted the indignities of segregation, and "Survivor" (1983), a striking bronze sculpture of a woman standing strong against adversity.

She also turned to monumental public art. In 1976, she completed a 10-foot bronze sculpture of jazz legend Louis Armstrong for New Orleans. Another major work, Students Aspire (1978), was installed at Howard University, a nod to the institution that shaped her artistic journey.

“She must have had a major impact,” said Everett. “Every time I mention her name, a student who came to study at Howard would say, ‘Oh, you know, Miss Catlett was one of my inspirations,’ and they’d light up.”

Recognition and Lasting Influence

Though she spent much of her life in Mexico, Catlett was eventually welcomed back to the United States. In 2002, her U.S. citizenship was reinstated, and she received numerous accolades, including an honorary doctorate from Howard University in 1996. Her work continues to be celebrated in major institutions such as the Smithsonian, the Museum of Modern Art, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

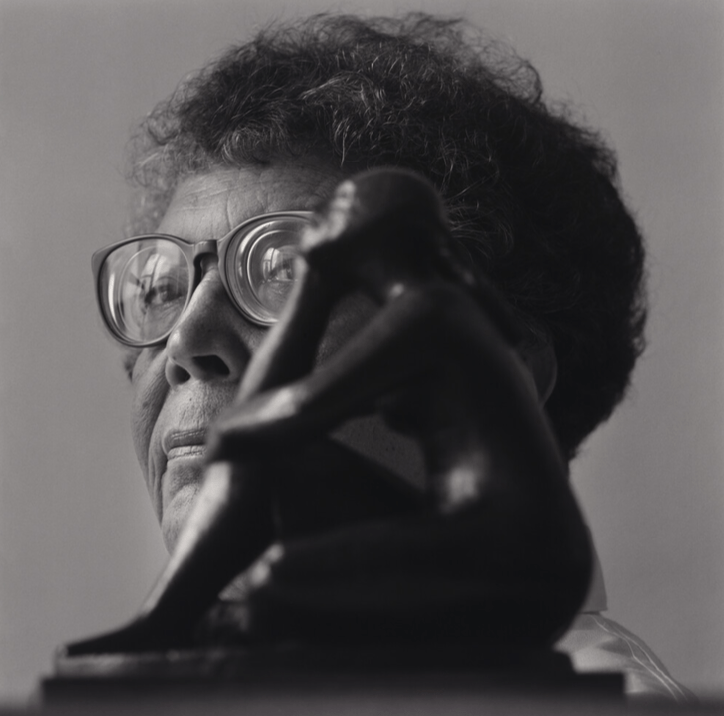

“If we sit before one of her sculptures, be it stone or wood, we really think about the kind of physical labor required to carve a form from just a block of wood, and that this was a woman that kind of had determination in all aspects of her life,” said Harvey.

Catlett passed away in 2012 at the age of 96, leaving behind a legacy of artistic excellence and activism. Her work remains a powerful reminder that art is not just for aesthetics — it is a force for change. “Music and art transcend time,” a fellow artist once said. “And if the person who conveys that message can reach generations beyond their own, that’s when it becomes important.”

“Her work speaks across generations, gender, and nationalities. She wasn’t confined to one decade or one issue — her messages continue to resonate with people today,” said Dean Everett.

Through her fearless vision, Catlett ensured that the struggles and triumphs of Black and working-class people would never be forgotten.

More on Dr. Harvey

Melanee C. Harvey is associate professor of art history in the Department of Art in the Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts at Howard University. She earned a Bachelor of Arts from Spelman College and pursued graduate study at Boston University where she received her Masters of Arts and doctorate in American art and architectural history. In addition to serving as coordinator for the art history area of study at Howard, she has served as programming chair for the James A. Porter Colloquium on African American Art and Art of the African Diaspora at the university since 2016. She has published on architectural iconography in African American art, Black Arts Movement artists, religious art of Black liberation theology and ecowomanist art practices. Melanee was in residence as the Paul Mellon Guest Scholar at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art during the 2020-2021 academic year. In 2023, she was awarded the Genevieve Young Fellowship in Writing by the Gordon Parks Foundation. Melanee is currently writing her first book, entitled, "Patterns of Permanence: African Methodist Episcopal Architecture and Visual Culture."