Photos by Simone Boyd.

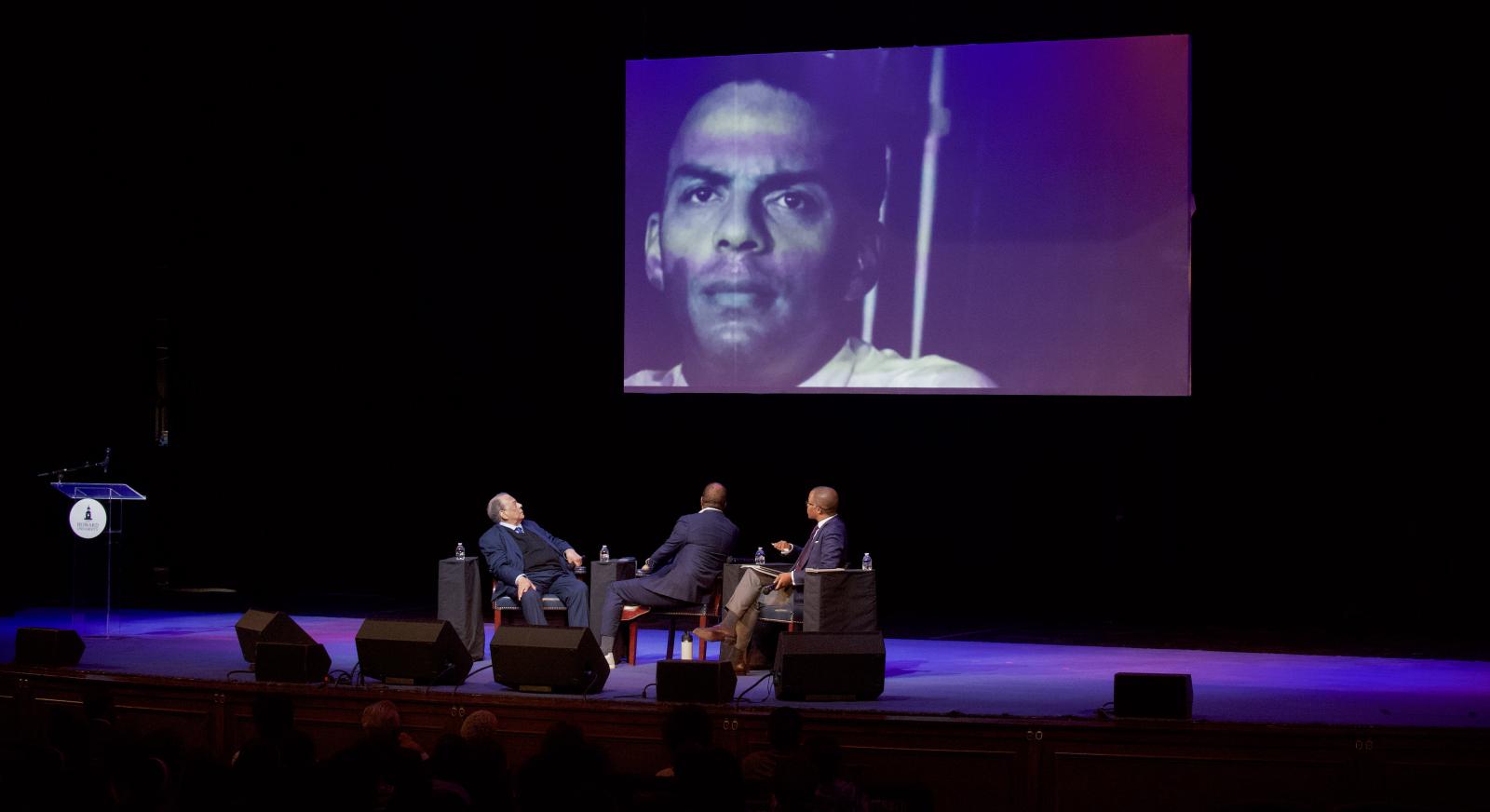

On Thursday, Oct. 9, Howard University welcomed one of its most distinguished alumni, Andrew Young (B.S.'51, LL.D. '77), for a fireside chat and tribute in Cramton Auditorium ahead of the premiere of his MSNBC documentary, “Andrew Young: The Dirty Work.” Young is an iconic American leader — champion of the Civil Rights Movement, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, member of Congress, mayor of Atlanta, and co-chair of the 1996 Summer Olympic Games. Moderated by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jonathan Capehart and joined by entrepreneur and civic leader John Hope Bryant, the program traced Young’s journey from his days as a Howard student to his global role as a human rights leader, and distilled lessons in leadership and moral courage for a new generation of Bison.

Moments like this continue to give proof to the fact that we remain at the center of the national and global conversations that continue to shape history.

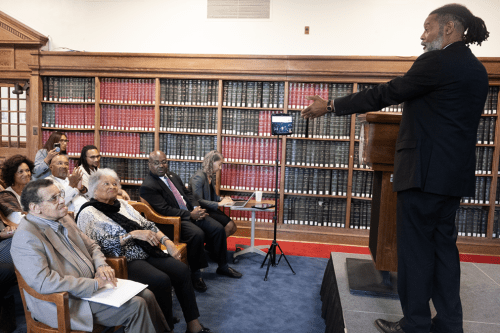

Opening the program, Wayne A. I. Frederick (B.S. ’92, M.D. ’94, MBA ’11), interim president, president emeritus, and Charles R. Drew Professor of Surgery, situated Young’s legacy within Howard’s enduring mission. Recalling personal moments with the ambassador, including witnessing Young receive an honorary degree in South Africa, Frederick underscored how Young’s life exemplifies leadership grounded in service.

Young’s visit, Frederick said, was a chance for students to “connect with living history” and to see Howard’s values at work on the international stage.

“Our campus has served as a bastion of truth and service for 158 years,” Frederick said. “Moments like this continue to give proof to the fact that we remain at the center of the national and global conversations that continue to shape history.”

The ‘Dirty Work’ That Changed History

Capehart opened by asking Young about the documentary’s title: the “dirty work” that others avoid but must be done if progress is to take root.

Young, who arrived at Howard at age 16, said he gravitated toward the unglamorous, necessary tasks: mimeographing flyers, answering Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s abundant correspondence, and mediating the internal disputes that kept the movement organized and effective.

“If there was something that I saw needed doing, it didn’t matter what it was,” Young said. “If nobody else wanted to do it, that was my job.”

That ethic was shaped by a maxim from his father and fellow Howard alumnus (Class of 1921) Andrew Sr., a lesson that became Young’s north star, “Don’t get mad — get smart.” Growing up in New Orleans amid racial tensions and open bigotry, Young learned to keep his composure and, instead of rage, let reason drive his actions.

“If you lose your temper, you lose the fight,” he recalled.

The mantra would become a signature of his negotiations with opponents in the South and, later, with heads of state.

St. Augustine and the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Among the afternoon’s most gripping moments was Young’s retelling of his earliest travels to St. Augustine, Florida, a major turning point in the fight for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

With the U.S. Senate locked in a filibuster, King worried that escalating demonstrations could spark violence and derail the bill. Young went to counsel restraint but instead was brutally attacked by Ku Klux Klan members as he tried to steer demonstrators back to safety. Klansmen later tried once more provoking Black community members to aggression, but their nonviolent discipline shifted national sentiment and created a moral backdrop for President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the landmark legislation.

In a documentary clip, Young quipped that it was “the most successful” beating he ever took, a painful yet pivotal sacrifice in service of a greater victory.

“If I had to take a few licks to get a Civil Rights Act, I’d do it any day of the week,” Young said.

Throughout the afternoon, Bryant regularly pressed Young to abandon his humility while describing his behind-the-scenes role in King’s orbit. For instance, Bryant divulged that while others were arrested as acts of witness, King often insisted Young remain free to translate between factions, soothe tempers, and carry messages from the jailhouse to the boardroom.

In a frank recollection, Young noted that King told him he needed someone “on the right” to hold the line so King could ultimately be the progressive force that the movement demanded.

“I need somebody to be reasonable and to balance out the emotions,” King told Young. “Unfortunately, that’s your job.”

If there was something that I saw needed doing, it didn’t matter what it was. If nobody else wanted to do it, that was my job.”