On Wednesday, Oct. 1, Howard theatre majors made a small but remarkable contribution to literary history in Founders Library. During the second day of the International Black Writers Festival, the students performed a stage reading of famed Ghanaian playwright Ama Ata Adoo’s 1964 “The Dilemma of a Ghost,” marking the second time the play has ever been performed in the United States.

A domestic satire revolving around the conflicts that arise when a Ghanaian graduate returns home with an unannounced Black American wife, the play explores the complicated tensions and the moments of deep understanding between the West and Africa and across generations, cultures, and gender.

“It was such a rich new experience, reading the text, pulling it apart, getting to know what it’s about,” said sophomore Alexandria Woods, who played the American wife, Eulalie Rush. “For me personally, diving into Eulalie was about finding the empathy and compassion, what her perspective is. It was about finding those moments where she’s strong and also where she allows herself to be incredibly gentle.”

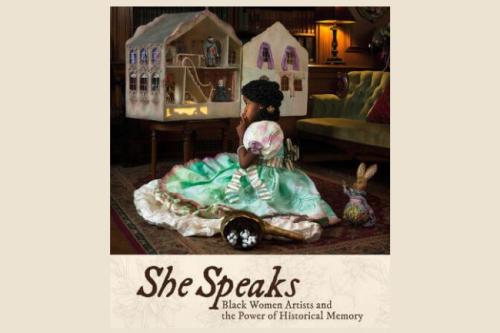

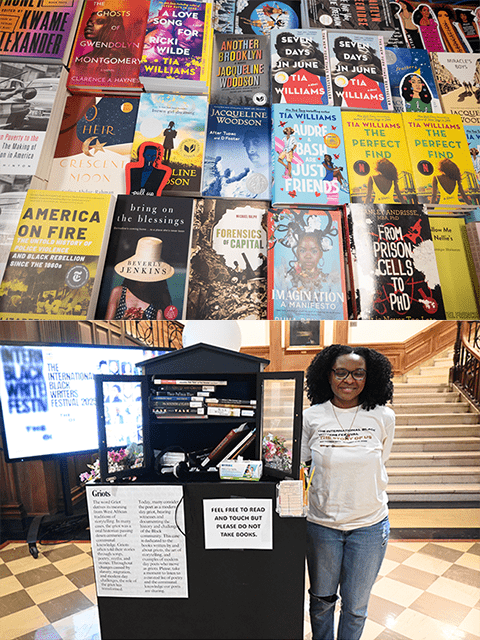

The performance perfectly encapsulated the festival’s theme of “The Story of Us,” meant to explore “how storytelling shapes identity, history, and imagination across generations and geographies.” Organized by the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, across three days writers, artists, and scholars delved into the history of Black literature as a preserver of memory, while also looking toward the future of Black storytelling. Along with writing workshops and a bookfair coordinated with Sankofa Café, Carpe Librum Bookstore, and D.C. Public Library’s Shaw Library, the celebration features panels touching on everything from the legacies of artists such as poet and photographer Gordon Parks to mass incarceration, AI, and Black authors' place within and outside the Western canon.

The Power of Framing

A powerful theme running through the festival was the way Black storytellers are able to challenge societal narratives and framings that dehumanize the underserved. In the presentation “A Poet and His Camera,” academic, police abolitionist, and curator Nicole Fleetwood explored how Gordon Parks’ photography was able to challenge mainstream narratives on inner city crime, even when accompanying those narratives on the page. Commissioned in 1957 by Life Magazine to take photos on the “rise in crime,” Parks’ approach told a far different story than the one written by a white reporter.

Rather than sensational depictions of vandalism, arrests, and shots that frame Black people and communities as inherently criminal, Parks focused on the police. Through photos that capture, for example, officers kicking down a door, patrolling a neighborhood in the dark, or watching inmates within a jail, the photographer tells a story behind the story of over policing, surveillance, and communities under threat of state violence.

“What he was doing with his camera was such an important form of storytelling that disrupts dominant narratives of criminality and the criminalization of Black people,” Fleetwood said.

Pushing against narratives that dehumanize was also a core focus of “The Story of Mass Incarceration.” The panel discussion, which included historian and author Elizabeth Hinton, American University anthropology professor Orisanmi Burton, and endocrinologist and Howard College of Medicine professor Stanley Andrisse, revolved around the use of evidence, personal story, and historical context when discussing perspectives on mass incarceration.

“I found myself in my early 20s in a courtroom looking at 20 years to life in prison, and having this prosecutor paint this picture of this dangerous threat to society,” said Andrisse, who described his experiences with the carceral state as a child and young man and the real-world power narratives can have over human lives. “Why would a human being want to send another human being to life in prison? How do you convince a judge to do that? You convince them that they are not human.”

During the panel, Burton brought up the writing of the late activist and revolutionary Assata Shakur, a figure who challenged the narratives that justify incarceration.

I want to introduce that there are different genealogies to understanding what prisons are, and one of the most important routes to understanding what they are is as a response to our Black revolutionary history.

“One of the things she writes is that Black people in the Western Hemisphere have always been prisoners. It’s easy to think of that as hyperbole, but she was being quite serious,” he said, citing the historical designation of enslaved Africans as prisoners of war being used as justification to continue slavery even after the slave trade was abolished. “I want to introduce that there are different genealogies to understanding what prisons are, and one of the most important routes to understanding what they are is as a response to our Black revolutionary history.”

Black Love, Resistance, and Expanding the Horizon of Black Literature

This rejection of assumed, simplifying narratives around Black lives wasn’t limited to nonfiction; throughout nearly every panel, authors across genres emphasized the need to expand our view of what Black literature has meant and can mean.

Prolific romance and historical fiction writer Beverly Jenkins described herself as a “kitchen table historian” during the “Black Love is Resistance” panel. Author of more than 60 books, she describes pulling from history on everything from the Great Exodus of 1879 to the history of Black female doctors in the 19th century, placing authenticity at the center of her stories.

“I don’t have to make it up,” she said. “When I first started, a lot of people would go ‘Oh did Black people really do this, did Black people really do that,’ so you get a bibliography in the backs of my books, so I don’t have to be questioned on my authenticity.”

Jenkins admits that uncovering these little-known histories takes a toll on her; but views it as essential to her craft.

“A lot of times I cry so my readers don’t have to,” she said. “Cause a lot of it’s painful. But we wouldn’t be here without the joy that also goes with it.”

Jenkins pulls heavily from Black historians for her work, citing Dorothy Sterling and John Hope Franklin, and emphasizes the need to source from a Black gaze.

“I knew our history, I grew up with Black history in the home, but the intricate details? That needed a Black gaze,” she said.

Beyond her practice as a writer, Jenkins also spoke of the need to not pigeonhole Black romance books as fundamentally separate from other romance books. The topic of segregating Black works and limiting the scope of what they can be was also the central topic of “Breaking the Canon: A New Era of Black Fiction,” moderated by Leslie Ann Murray, founder of Brown Girl Book Lover.

If we think about American mythology, if we think about Black people, Black people have upended Western-ness

Murray opened the event with a memory of graduate school, reading Gloria Naylor’s novel “The Women of Brewster Place.” The book, which follows the interconnected lives of seven Black women in housing projects in an unnamed city, was structurally bold and experimental, and has gone on to change the way authors approach short story writing. However, Murray notes, the publishing industry did not treat the book as such.

“Tayari Jones, my professor at the time, lamented that Black fiction writers were not celebrated for their structural and creative and creative innovations, and are segregated to social issues,” she explained. “Race, income, equality, gender, etc. While these issues are important to discuss, they’re always deemed insular. Fifteen years later and I’m still processing Tayari’s words.”

Murray went on to lead a panel with Namwali Serpell, author of “The Furrows,” and Samiya Bashir, author of the poetry collection “I Hope This Helps,” exploring how Black writers have been ignored for their technical and stylistic contributions to the canon.

To illustrate this point, Serpell brought up everything from W.E.B. Du Bois’ under-discussed science fiction writing to the massive influence of Black voices and culture on Mark Twain’s life. She also discussed the complexity and experimentation in Howard alum Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” from the running Dick and Jane parody in the opening prologue to the larger structure of the book as a story of a young Black girl told entirely by other people.

“When people talk about ‘The Bluest Eye’ they talk about the message,” she said. “They don’t talk about incredibly formal, groundbreaking innovation. … I mean these are really radical things she’s doing, and nobody wants to talk about them.”

Bashir also pushed against the idea that Black authors are “outside” of the canon, instead arguing that they have not only always been integral to literary history but the most consistent innovators within it.

“If we think about American mythology, if we think about Black people, Black people have upended Western-ness,” she said when asked what “breaking the canon” means to her personally. “And that’s kind of our job, I think. It’s kind of like breaking a chain — it doesn’t mean I hate metal. I just don’t like chains.”

These were just a few of the incredible discussions over the course of the festival. To experience them yourself, visit the Moorland-Spingarn YouTube page, where you can find recordings of every panel from Oct. 1 and 2, or watch them below.