How many hours a day are you looking at a screen? From our laptops to our televisions and our smart phones, screen time is a nearly unavoidable fact of life, especially on the heels of a pandemic that forced many of us to do our jobs, go to school, and even hang out with friends completely virtually. While this technology has made us more productive and connected us to others around the globe, a growing body of evidence suggests that excessive screen time is harming us mentally and physically in ways that go far beyond just “doomscrolling.”

Worse yet, the most severe impacts are being seen in school-aged children.

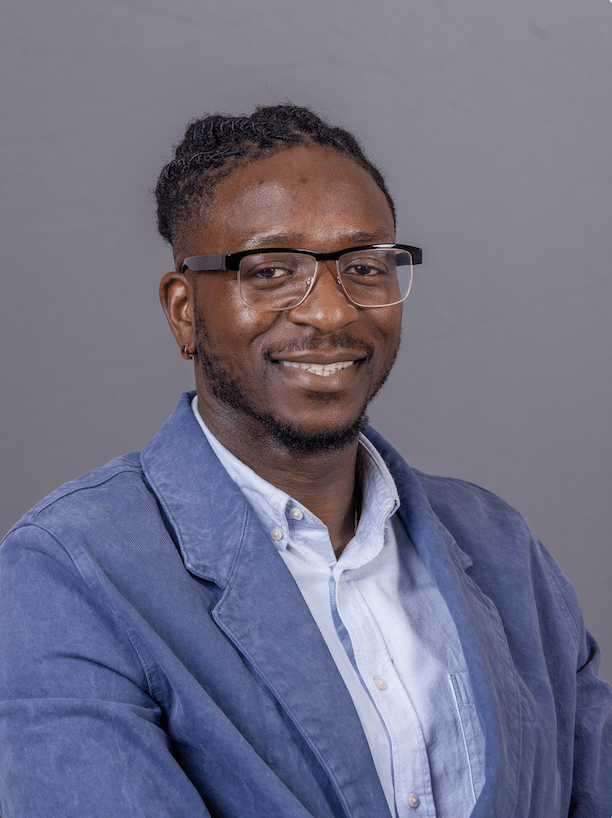

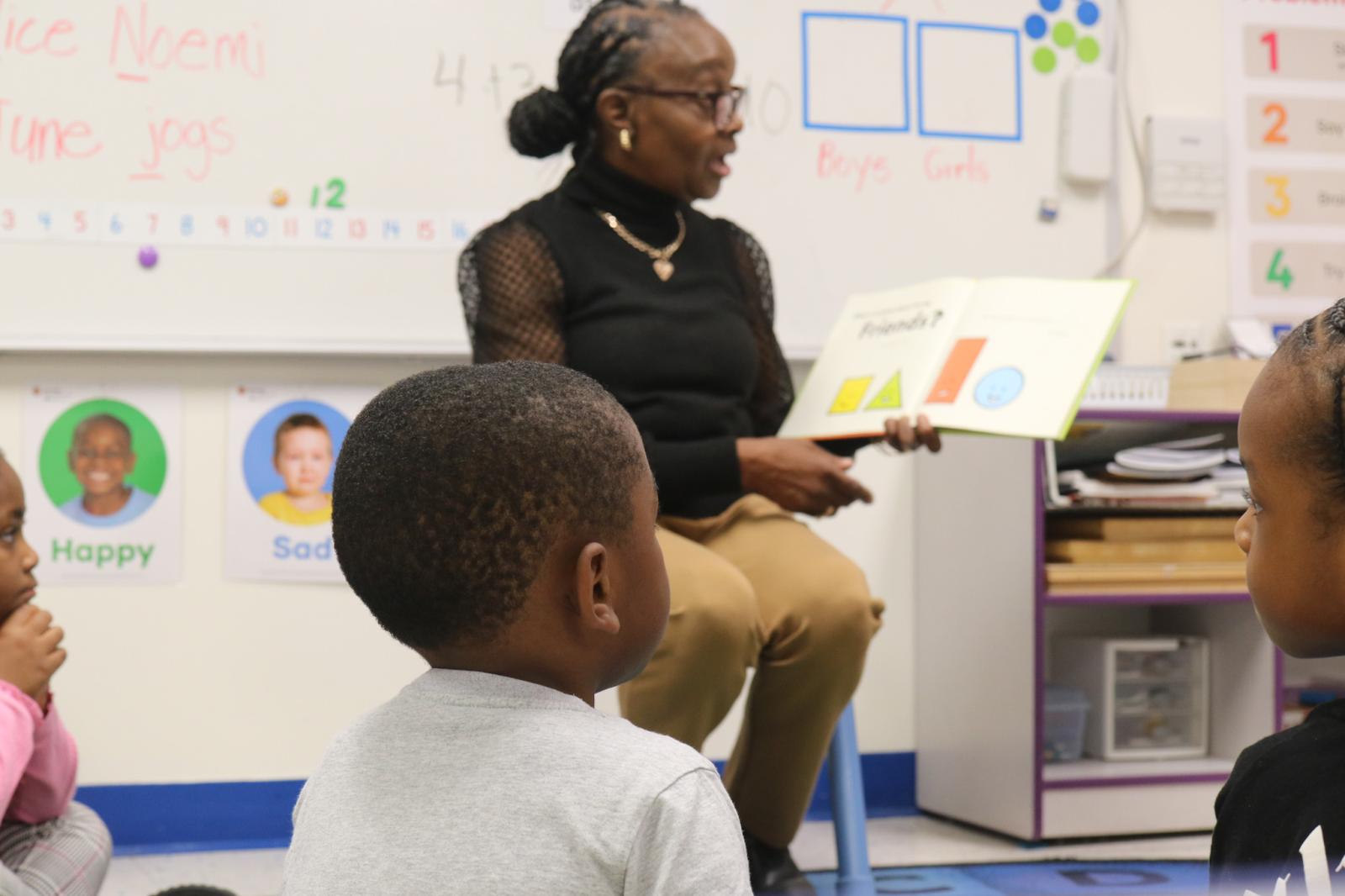

As part of our new “Get Yourself Together” series aimed at giving you tips on improving your overall health and wellness, three Howard University educators and researchers — Dr. Kisha Lee, Howard University Early Learning Program (HUELP) Director; third-year Higher Education, Leadership and Policy Studies program doctoral student Olawale Kuponipe; and psychologist and professor Dr. Kamilah Woodson — break down the scope of “screen addiction” and ways you can reduce your and your kids’ screen time.

Screen Time and Cognition Are Definitely Related … Somehow

There are many challenges to pinning down exactly how screen time affects our brains. However, it is undeniable that there is a link between screen time and mental and cognitive issues. A 2024 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study found that 50% of children aged 12-17 reported being on a screen for over four hours per day. Within that demographic, the study determined that those children were reported to have severely higher rates of depression than children with less screen time activity, in addition to more than 27% of teenagers with high screen time reporting anxiety or depression symptoms in the last two weeks during time periods between July 2021 through December 2023.

Beyond general anxiety and depression, research has also found a link between screen time and a range of disorders and cognitive problems. According to an article published in The International Journal of Eating Disorders, screen time has been identified as a risk factor for binge eating disorders. Screen time has also been linked to suicidal behaviors, suicidal ideation, and mental health outcomes in youth, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Additionally, a review on current studies published in the Cureus Journal of Medical Science concluded that screen time can have negative impacts on sleep quality, emotional regulation, language development, and executive functioning, especially in younger children.

“When children come into organized childcare, it’s difficult for them to follow instructions,” said Kisha Lee. “It’s difficult for them to focus. They’re easily distracted, some of which could come from the extra screen time that they’re getting.”

It would be a massive oversimplification to blame all of these negative outcomes on the sheer hours of screen time. The JAMA study — which tracked the mental health and screen use of more than 4,000 children over four years — emphasized that suicidality was not correlated with total screen hours but rather with addictive use based on participants’ reporting of factors such as compulsion, withdrawal, lack of control, and distress around their phone. According to Olawale Kuponipe, the pandemic only intensified this addiction.

“The withdrawal effect of coming out of the COVID-19 was instant because a lot of kids had to use technology to actually log into school, log into courses, and things of that nature,” he said. “I think now it’s at all time high just because of the fact that a lot of parents have to work [and]the workload that they have to put in to monitor their children is a lot on them mentally.”

Other studies have found that the relationship between anxiety, depression, and screen time is a messy feedback loop rather than a direct causal relationship. Teens experiencing mental health stress may be more likely to up their screen time, which in turn adds further stress.

“This is their life now, their life is screens and computers,” said Kamilah Woodson. “It’s impacted the way we rear and teach our children, so it may be that their brains, the chemistry, [and] the neuroplasticity shifts because it’s necessary, almost like evolution. I’m less inclined to go so far as to say that screens are completely dangerous, but I would say that it’s nuanced. It’s not just time; it’s about the what, when, why, and how they’re using their computer or their phone.”

Woodson emphasized that there are even benefits to screen use, and rather than a total cut-off of screen time, one approach for better “digital mental hygiene” is to ensure the content is supportive of a child’s development.

“The phone can be addictive,” she said. “I have a 9-year-old and it’s like a third appendage — he doesn’t want to do anything without his phone. At the same time, he's looking up things that are related to quantum physics, playing games where he’s learning vocabulary, and so it does matter what they’re watching and when they’re watching it.”

Keeping Kids’ Attention in a New World

Generation Alpha, born between 2013 and 2025, was affected during the most crucial years of instruction during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Many teachers are now saddled with teaching students who haven’t grasped the foundational concepts needed to matriculate successfully, according to Lee.

“We’re seeing that their scores for assessments on reading and writing are lower,” said Lee, a sentiment backed by the most recent Nation’s Report Card. “Even some with mathematics, a lot of the reasoning has decreased in children. We understand that technology is a huge tool, but for children, a lot of times it’s more important for them to develop those skills physically and to be outside. Children know how to swipe before they know how to read or write.”

Kuponipe added that a study based in Ontario, Canada noted how school administrators are "trying to practice a thing called screen hygiene, where they give children 20/20/20 breaks throughout the day.

“They allow them to actually be rewarded for things that they do at school with a 20-minute break to be on their phone because they're so addicted,” he explained.

As educators and parents feel like they’re trying to play catch-up to keep the COVID-19 generation from falling behind, new technologies are adding new difficulties.

“I think the advent of AI has also intensified technology use even more so than post-COVID because kids are very curious and their attention spans are lower now than ever,” said Kuponipe. “I think it’s a dangerous phenomenon and there's many, many sides to it.”

Educating Parents on Screen Time Practices

Lee encourages parents to facilitate play out of the home as much as possible. Despite guidelines to keep screen time for children ages 2 to 5 under one hour a day (and to avoid all screen time for children 0-2), many children have been reported to spend at least three hours a day online — that’s 21 hours a week, essentially a part-time job of looking at screens.

“We’re finding that children have less physical mobility, such as being able to run, jump, hop, ride tricycles, and things like that,” said Lee. “Children are more cautious about the world. Things like starting them with swimming lessons, starting them with soccer, and gymnastics is [helpful].”

Many parents are still learning how to balance technology with traditional home rearing, which has inspired Lee to take a more collaborative approach with parents at HUELP.

“I do Lunch & Learns with our parent community,” she said. “Starting this semester, we’re doing [up to] three Lunch & Learns. The first one is on parenting styles and then we’ll have a series of six, three per semester. One of the things we recommend is that you reduce the screen time.”

Many parents have become reliant on screen-time as a parenting tool for their children, oftentimes using it as a bargaining tool or as a distraction. This cycle can disrupt development. Lee recommends that parents ween their children (and themselves) off of screen time one hour less per day progressively. In lieu of screen time, she suggests parents should increase playtime with their children. She explains that there are many things that parents can do to enter the creative process with their children.

“What we try to do is to replace that screen time with something fun,” Lee said. “Do a cooking activity, come up with something that your child loves to do, and play with them. They may have cars, or play with magna tiles. Play with them. There’s so much you can do with science. You can order kits online for stuff for kids to do. Replace that with their face being in front of a screen.”

The Right Way to Use Screens

Since children are native to the digital age, Howard experts explain that it’s best to utilize technology as a tool rather than a bargaining chip.

“I wouldn’t use screens as a reward,” said Woodson. “Set boundaries and routines. Encourage people to identify the purpose for which they’re using the device in the moment — are you using this for information, communication, or just out of habit?” This method right-sizes online media, such as entertainment on social media and video games, to be used as a supplement to children’s lives.

Lee, Woodson, and Kuponipe advise that society should not be so engrained online that they miss out on real world experiences.

Therefore, screen hygiene is paramount to a child’s success. Woodson makes it clear that since children are impressionable, and it’s up to parents to model the type of screen hygiene they want to see.

“Maybe the screen goes off two hours before bed, maybe there are screen-free zones like no screens at the table or in bedrooms,” said Woodson.

Screens aren’t all bad, and parents can find uses for them that support their children, if they do so actively and responsibly. Neurodivergent children, for example, can benefit from watching lessons and interacting online with similar diagnoses. This can serve as a major tool for parents who need to find community when there may be limited opportunities. Additionally, parents and children can watch content together and discuss it afterward, creating a shared experience where children and parents can bond.

“We have to do our best to insulate them with all the things that make them amazing, secure, and comfortable so that when they go out into the world they’re insulated,” said Woodson.