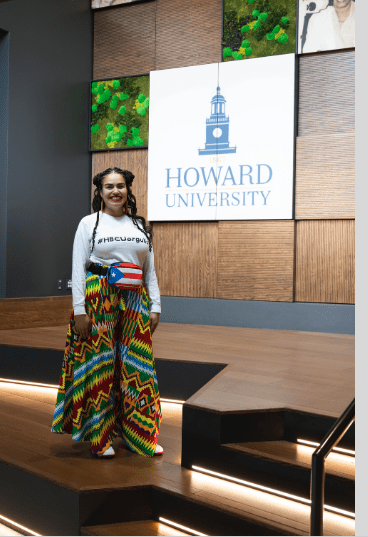

Stacey Speller calls herself an “HBCU Nuyorican” (a term used to describe Puerto Ricans located in or from New York) through and through. Born and raised in the Bronx to Puerto Rican parents with Black and Indigenous roots, Speller proudly wears her Afro-Latine identity in every room she enters. A member of Howard University’s Higher Education Leadership and Policy Studies program’s fifth cohort, she is authentic and has an infectious energy. She can often be found adorned with accessories that speak to both of her identities — a fanny pack with the Puerto Rican flag and bamboo hoop earrings.

Now, just days away from being officially named Stacey Speller, Ph.D., she is using her lived experiences to reshape the way the world thinks about race, higher education, and identity through her dissertation, “Somos Dos: Institutional Leaders’ Sensemaking of Being a Racialized Dually Designated Historically Black College or University (HBCU) & Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI).” Inspired by Robert Palmer, Ph.D.’s Minority Serving Institutions in Higher Education course, Speller’s research highlights a growing but often overlooked phenomenon in higher education. She describes it as a study that explores how institutional leaders at HBCU-HSIs make sense of their racialized dual identity — how they make sense of the opportunities/challenges of being both HBCUs and HSIs. In her words, “What does it mean to be both?”

While preparing for her dissertation defense last month, Speller said,

I dedicate this work to every Black, Afro-Latine, and/or Latine student who has been part of an HBCU or will be in the future. You are seen, you are valued, and you most certainly belong.

I had never heard of this dual designation before my first semester at Howard,” Speller shared. “When I realized that there are HBCUs with over 25% Latine student populations — enough to qualify for HSI status — I knew I had to explore it. It was speaking to every part of my identity.

Speller’s study takes a layered approach — examining this hybrid institutional identity through the voices of university presidents, vice presidents, directors, and national policy advocates.

Her goal is to understand how these leaders make sense of and operationalize an institutional identity that exists at the intersection of two distinct designations—one rooted in historical mission (HBCU) and the other driven by contemporary demographic thresholds (HSI). While both are racialized within the higher education policy landscape, they must not be conflated. HBCUs carry a legacy of systemic underfunding and resistance born from exclusion, and the HSI status reflects shifting student body populations rather than a founding mission of serving historically marginalized communities.

Through interviews with internal administrators and external stakeholders, Speller gathered insight at the macro, meso, and micro levels — analyzing everything from federal funding policy to how students, faculty, and staff experience these spaces. “It’s not just about numbers,” she emphasized. “It’s about how identity gets translated into practice, into policy, and into the lived experience.”

At the heart of Speller’s inquiry is a striking policy contradiction. Under current federal guidelines, HBCUs cannot access Title V funding allocated for HSIs — even if they qualify based on their demographics. “It’s considered ‘double-dipping,’” she explained. “But what does that say about how we value our institutions? This is another layer of injustice, another layer of anti-Blackness embedded in federal education policy.”

Her critical lens challenges traditional narratives of racial categorization and institutional exclusivity. “Society often says you can only be one thing — you’re either this or that,” said Speller. “But that’s not the reality on the ground. These institutions are already bringing communities together. My research asks: What if our policies and support systems reflected that?”

Speller’s own path to this work is just as compelling as her findings. A first-generation doctoral student, she was adamant about obtaining all of her post-secondary education from HBCUs. She earned both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Bethune-Cookman University, where she was recruited to play tennis after attending a showcase event. Despite full-ride offers from elite institutions like Williams College and UMass Amherst, Speller knew early on that an HBCU was home. “At those PWIs, the microaggressions were loud,” she recalled. “But when I visited Bethune-Cookman, I saw a diverse tennis team with members who looked like me, spoke Spanish like me, and a campus that felt like community.” She credits her Godfather (pictured), who she “cannot thank enough for introducing me to the world of HBCUs

That choice was transformational — and so was her decision to come to Howard. Moving to D.C. while her husband and three children remained in Florida during her first year was one of the most difficult sacrifices she’s ever made. But Speller remained motivated by faith, community, and her mission. Speller says before being a student, researcher, summer scholar, co-chair, advisor, mentor, thought-partner, co-conspirator, entrepreneur, and advocate, she is “a God-fearing wife and mother.” “I did this for my children (pictured). I did it for my ancestors. I did it for my HBCU and Afro-Latine communities. This research is my gift back.”

Looking ahead, Speller is building a data-driven future rooted in advocacy and storytelling. She is the founder of HBCUorgullo — a nonprofit initiative whose name means “HBCU pride” in Spanish — and is developing Orgullo Stories, a digital media project that captures the voices of Afro-Latine students, alumni, and leaders in HBCU spaces. She’s also planning new quantitative studies to help shape federal policy.

“Right now, Black and Latine communities are under attack in different but connected ways. The goal of this research is to unite us, not divide us,” she said. “We are the global majority. It’s time we start acting like it — together.”