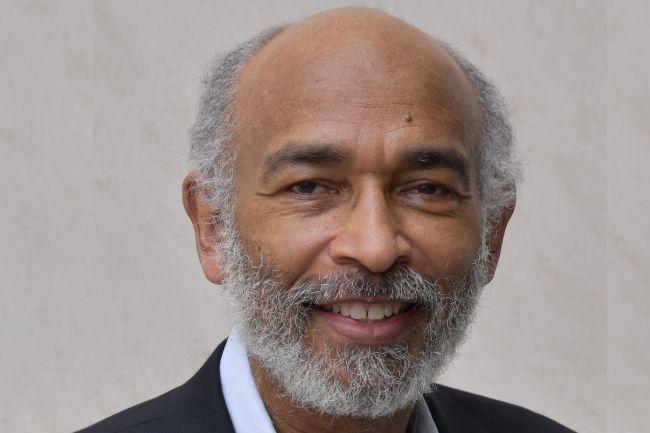

A globally recognized statistician, computational neuroscientist, and anesthesiologist, Dr. Emery Neal Brown’s groundbreaking research and statistical methods have revolutionized how we analyze neuroscientific data, leading to advances in science’s understanding of circadian rhythms and how the brain functions.

Throughout his career, he has received the National Medal of Science and a Gruber Prize in Neuroscience, and been accepted to the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine — one of only 19 scientists in the world and the first African American elected to all three academies.

A Real Doctor

Brown, who is receiving an honorary Doctor of Science degree during Howard University’s 157th Commencement Convocation, describes his primary research motivation as “the joy of problem solving.” But there is a deeper layer when it comes to his anesthesiology work.

For most of its history, anesthesia usage has focused on patient symptoms and inexact measurements. Brown’s work is shifting the focus on how anesthesia directly affects the brain, such as by lowering the oscillation rate of brain waves to induce unconsciousness. This neuroscientific approach is not only leading to more precise anesthesia use — and therefore less negative side effects and errors in dosing — but could also uncover new ways to study a range of effects in the brain, including mental illness.

“With the anesthesiology research, it was an Interesting problem. I think we can solve it; if we solve it the right way, we’re going to have an impact on an enormous amount of people across the world,” Brown explained, estimating this work could impact upwards of 300 million people.

“But it goes deeper than that. Anesthesia is another way to study the brain,” he continued. “For example, you’ve probably heard how one anesthetic, ketamine, is used to treat depression. So, if I understand in a deep way the properties of anesthetics, then we can have a better way of understanding how the ketamine is working and design new approaches to treating depression.”

The first thing I tell them is ‘you’ll be a doctor.’ I’m quite frank about it, you’ll be a real doctor,”

This direct impact on patients has been a profound driver for Brown. “Just the thought that someone's going to wake up and feel good and not be sick after anesthesia or that the anesthesia could help them maybe get over depression because you're designing new therapy,” he said. “That's quite frankly very, very gratifying.”

Brown strives to impart this motivation to the next generation of anesthesiologists. “The first thing I tell them is ‘you’ll be a doctor.’ I’m quite frank about it, you’ll be a real doctor,” he said. “If you've been on a plane and someone says, ‘is there a doctor on the plane?’ you can feel good, because that's all we do is we handle situations like that — second to second, day after day. Just that alone is huge.

“But then knowing you'll be a real doctor who's a scholar that has a deep understanding of not only how the cardiovascular system works, how the pulmonary, respiratory system works, but now how the brain works? That skillset doesn’t reside in a lot of other medical professions,” Brown said.

Brown’s pitch, while simple, is effective. His mentorship has had an enormous impact, and his former students continue to pursue important work in institutions including MIT, University of Pennsylvania, and the University of California, Berkeley.

Leveraging the Position of HBCUs

“Any time someone takes the time to read your work and tell you that it’s good, it’s quite humbling, to be honest,” Brown said about receiving an honorary degree from Howard, calling it “a tremendous honor.”

His admiration for the University stems from its history not only as a world-class research institution, but as a leader among historically Black colleges and universities. Brown is deeply familiar with the value of HBCUs, his own parents having met at North Carolina A&T, and views Howard and other HBCUs as essential to solving challenges in medical research.

“As far as medical research, an R1 university is what Howard is categorized as now, and necessarily they’re taking strong interest in issues that affect the African American community,” he said. “And we need that, because we’re so far behind in so many ways, and that is going to be a real plus for us.”

No one's going to be more interested in us than we are in ourselves.”

Brown has seen the positive impacts of both his own work and the work of HBCUs firsthand. “I had the good fortune of having students tell me, ‘I'm thinking about going to anesthesiology because I heard your lecture or I've seen what you've done,’” he said. “And I mean that's inspiring for me, quite frankly, to hear that and then to realize that the students are looking for role models. They're looking for trying to figure out what paths they can pursue.”

This impact is incredibly important to addressing the issues faced by the Black community. “I think that pulling more African Americans into medical research through STEM is going to, in the long run, benefit our community tremendously,” Brown concluded, “because no one's going to be more interested in us than we are in ourselves.”