Remember when time capsules were a thing?

For the uninitiated, groups of (mostly) students nationwide would accrue the items they felt best represented their era, stow said items in a container of some sort, and hide said container to be one day discovered by future generations as evidence of how we once did things on planet Earth.

Think of this, our SAVE THE CULTURE series, as a modernized version of the time capsule. In 2025, a quarter of the way into this pivotal century and nearly 100 years since the iconic Harlem Renaissance — an era that profoundly shaped Black artistic expression and cultural identity — this project feels especially urgent.

Throughout the summer, our editorial team will be designating 20 (or so) of the works most essential to understanding the Black American experience, in genres ranging from film and television to music and literature, and so much more in between. By spotlighting these landmark creations, we aim not only to preserve and honor the rich legacy of Black culture, but also to inspire ongoing dialogue, foster greater appreciation, and provide future generations with a vibrant record of how our culture thrived at this defining moment in history.

Black fashion and beauty are not simply “looks”; they are records of how the Black community lives — their fights, their wins, their joy. Braids, lettuce hems, sneakers, nails: each holds a story. They document history, push back on stereotypes, and make dignity visible. And even when due credit was not given, Black style kept setting how America got dressed — from the runway to the boardroom, from the choir stand to the sidewalk, and now across our social media feeds.

From the Harlem Renaissance to now, consider this an invitation to look back, look forward, and keep the receipts. You’ll find categories, individuals, items, and movements that together capture the richness of Black creativity. We built this list with Kahlana Barfield Brown (B.A. ’04), Howard alumna, fashion and beauty editor, TV correspondent, and creative/brand consultant, and Dr. Elka Marie Stevens, associate professor of visual culture and studio art at Howard, Fashion Design program coordinator, and curator of the Fashion, Textiles and Accessories Collection.

Roots, Pride, and Resistance

1) Afros

In the era of Black Power, the rounded natural silhouette turned hair into a manifesto, from campuses to catwalks, protest lines to magazine covers. “The Afro was a political statement — a declaration of pride, power, and identity,” said Barfield Brown, echoing the rallying cry of “Black is Beautiful.” Models and public figures wearing afros helped reset beauty standards well beyond the 1970s.

2) Cornrows

Centuries-old African braiding carries lineage, geometry, and skill, passed from hands to heads in patterns that speak their own language. “Cornrows are a direct link to our African roots … carrying a piece of our history on our heads,” Barfield Brown noted. From classrooms to red carpets, their endurance resists erasure and keeps heritage visible.

3) Natural Hairstyles (the policy shift)

From Black is Beautiful to Black Lives Matter, natural hair has and continues to push back on Eurocentric rules at work, in schools, and on television. Popularized during the “Black is Beautiful,” “Civil Rights,” “Black Power,” and “Black Lives Matter” movements of the 1920s, 1960-1970s, and 2010s, the wearing and acceptance of natural hairstyles has increased.

“Several states have passed the 2019 CROWN Act, which stands for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair, legislation that protects discrimination toward individuals and groups who don race-based styles such as braids, locs, twists, and knots in the workplace and public institutions,” Stevens added.

4) Dashikis and African-Inspired Attire

Adopted in the 1960s as a nod to diasporic pride and resistance, the dashiki became a wearable bridge between Africa and America. Stevens situates today’s instantly recognizable prints within 20th-century textile production — intertwined with older garment traditions — so that every tunic stitches identity to everyday dress. “Although African Americans did not invent the dashiki, they incorporated the East African-inspired garment into their daily lives during the Civil Rights and Black Power movements,” Stevens said.

5) Denim

Once tied to enslavement and prison labor, then to organizing and solidarity, denim traveled from fields and shop floors to a global wardrobe. Activists in the 1960s used it to signal class alignment and resistance; by the 1980s, designer jeans turned the fabric into status. As Stevens reminds us, every pair still holds those layered histories, even when styled for luxury.

Street Codes and Status Symbols

6) Air Force 1

Dropped in 1982 and canonized by early-2000s East Coast hip-hop culture, a crisp white pair of Air Force Ones, affectionately nicknamed “Forces” became the neutral that goes with everything and spoke volumes. “Classic, clean, universal,” Barfield Brown called them — minimal form, maximum meaning, and a code you can spot from across the block.

7) Jordans

Debuting in 1985, Jordans fused sport, status, and storytelling — mixing colorways with lore, releases with ritual, and neighborhood desire scaled to the world. The collaboration between Michael Jordan and Nike didn’t just sell sneakers; it transformed sneaker culture and vaulted sportswear into a global industry. A pair of Jordans is the perfect addition to a high-fashion outfit, an ode to culture. “Jordans became a symbol of status, style, and loyalty. Michael was OUR favorite athlete and we wore his shoes with pride. They showed how sports, fashion, and Black culture are deeply intertwined,” Barfield Brown said.

8) Designer- and Logo-Centric Fashion

Luxury houses once set the rules; Black communities rewrote them. In the 1970s and 80s, amid hip-hop’s rise and celebrity culture, logos and designer goods became street authority as much as status symbols.

“Custom wear by Dapper Dan featuring brand logos contributed to heightened desire African Americans, particularly those belonging to entertainers and celebrities, to flaunt designer and luxury branded goods. Louis Vuitton and Gucci handbags are a part of Black fashion history,” Stevens added.

9) Kangol Hats

Flat-brim and bucket silhouettes crowned the swagger of 1980s hip-hop — instantly readable, permanently cool. “From LL Cool J to Run-DMC, Kangol hats became a symbol of cool,” Barfield Brown said, a brim that still communicates with one glance.

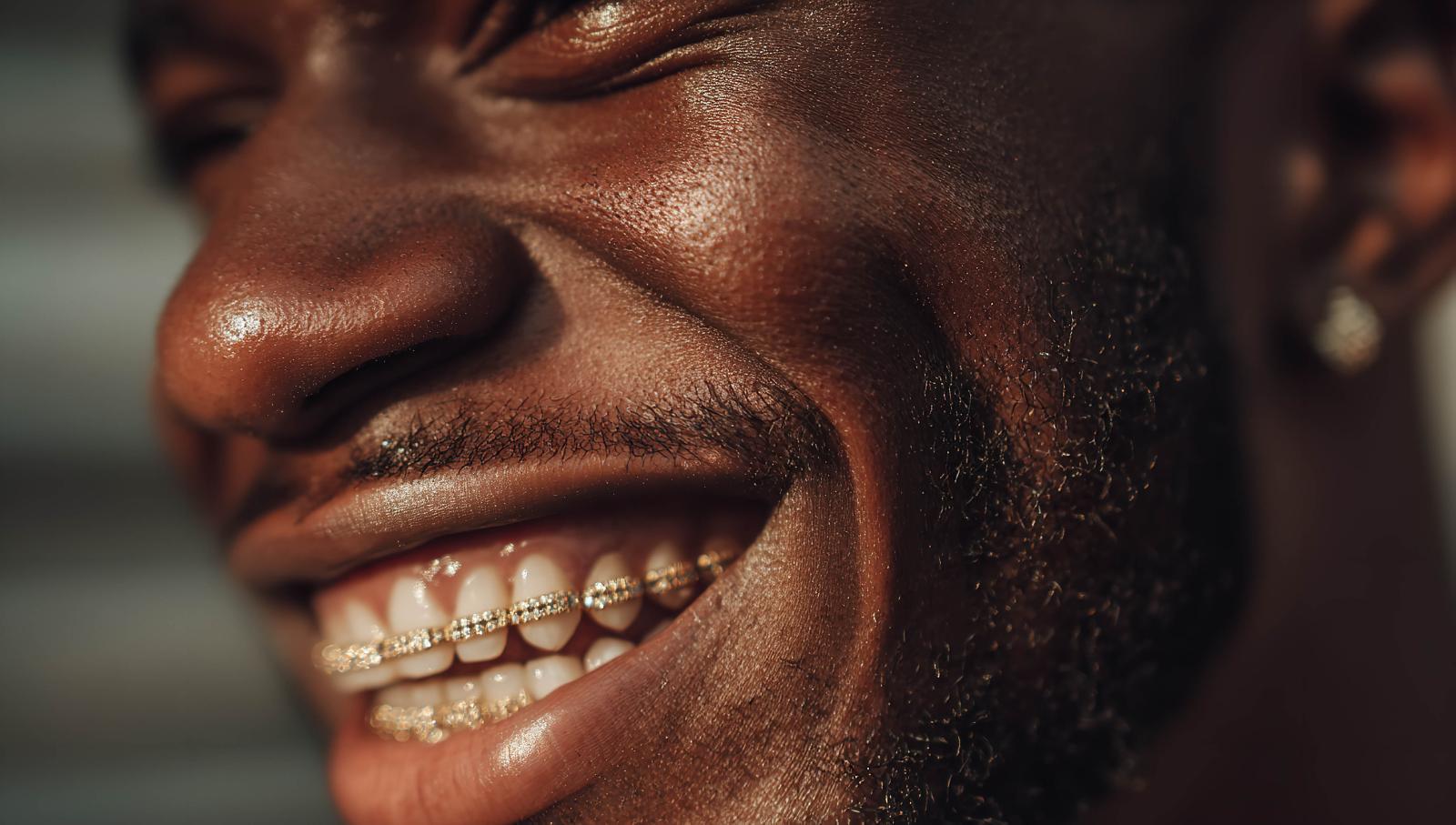

10) Gold Grills

Removable gold or diamond mouthpieces turned smiles into jewelry and self-possession into shine, especially across Southern hip-hop culture in the ’90s and 2000s.

“Grills were pure self-expression,” Barfield Brown added.

Craft, Beauty and Technique

11) Finger Waves

Harlem Renaissance elegance sculpted close to the scalp, finger waves require precision hands and frame the face like fine calligraphy. Think Josephine Baker — whose stagecraft reshaped global ideas of Black beauty — dressed at times by visionaries like Zelda Wynn Valdes, whose gowns married sensuality and elegance.

12) Nail Extensions

Nail adornment is ancient; modern acrylic systems (introduced mid-20th century in the United States) turned fingertips into portable canvases and, in Black communities, a visible marker of status, craft, and beauty. By the 1970s, Vietnamese refugee entrepreneurs were building salon ecosystems as singers like Diana Ross and Donna Summer brought glossy acrylics into mainstream glamour. The 1980s sent nail culture to an unlikely stage: Olympic champion Florence “Flo-Jo” Griffith Joyner shattered records — then expectations — with long, decorated nails, body-con uniforms, luxe hair, and full glam, setting a bar that athletes, entertainers, and everyday women still reach for.

13) Stiletto Nails

Long, pointed, and unapologetic, stiletto nails micro-architecture that announces attitude before a word is spoken. “Black women have led nail trends for decades — art, attitude, and femininity,” Barfield Brown said, and the media megaphone only magnifies that leadership.

14) The Lettuce Hem

A rippled, overcast edge gave knit garments their swing on dance floors and runways. Designer Stephen Burrows — one of the first Black Americans to sell collections internationally — helped define the look, carrying disco’s kinetic joy straight into contemporary fashion. “Brightly colored, flowing, jersey fitted disco garments from the 1970s New York dance scene were the cornerstone of his aesthetic,” Stevens stated.

15) Hoop Earrings and Gold Jewelry

With roots in Nubia — where round gold earrings carried spiritual meaning — gold hoops became everyday regalia for Black America. In the 1960s and 1970s, large, plain circles could finish any outfit; by the 1980s, bolder variations in size and finish commanded attention. Drawing on New York City streetwear, hip-hop culture elevated gold hoops from accessory to signature, a status that endures today. Even as overall U.S. demand for gold dipped in the 1980s, Black communities embraced gold as a language of presence and pride.

“Gold rings, bracelets, and necklaces displaying the wearer’s name and large chunky neck chains were also popular accessories for stylish individuals, Hip Hop celebrities, in particular,” Stevens noted.

Icons, Maintenance, and Everyday Influence

16) Do-rags

Silky ties protect waves, braids, and fresh cuts; the fabric, knot, and tail do double duty as practical care and public style. “From maintenance to statement — pride and practicality in one,” Barfield Brown said, honoring self-care as culture.

17) Bamboo Earrings

Oversized, segmented hoops born of ’80s and ’90s New York City traveled from block parties to boardrooms without losing their bite. The accessory became an archetype; the line that named it became proverb.

18) Streetwear and Athletic Wear

Streetwear — born of urban youth — braids leisure, sport, and designer sensibilities: tracksuits, tees, denim, sneakers, later spliced with surf and skate. The 1980s-90s music video era was rocket fuel. Willi Smith (WilliWear) democratized fashion and laid the groundwork for the category; without him, it’s hard to imagine a Virgil Abloh at the helm of a luxury house. Run-DMC’s “My Adidas” put sneakers on a global pedestal, pairing Kangol® hats, track suits, oversized chains, and shell toes into a uniform that jumped from block to arena. The Air Jordan partnership turned athletic wear into a lasting lifestyle — and a worldwide status language worn from office to wedding. “Athletic shoes (aka sneakers, trainers, and kicks), in particular, have become global status symbols appearing across and worn with categories of dress from office to wedding wear,” Stevens said.

19) Icons: From Baker to Beyoncé

Icons teach the world how to look. In the 1920s, Josephine Baker — politically astute and outspoken — forced global audiences to reconsider Black beauty and American identity through performance and dress. In the 1960s, Motown’s in-house designer Michael Travis helped make The Supremes a blueprint for aspirational glam, with coordinated gowns, hair, and poise that reset standards. Since the 1990s, Beyoncé has treated fashion as a visual language — from “Formation” to “Renaissance” to “Cowboy Carter” — to speak liberation, pride, and belonging, often spotlighting Black designers (with early looks crafted by Tina Knowles). These are only a few of the women whose images continue to shape how everyone presents themselves.

20) Michelle Obama

First ladies wield influence and draw scrutiny — but only one carried the representational weight of the first Black first lady. From Barack Obama’s campaign through two terms and beyond, Michelle Obama used fashion to amplify broader platforms: education, family, veterans, and food security. Frequently featured on consumer magazine covers, she modeled a vision of Black womanhood that was professional, elegant, and accessible, while deliberately championing Black designers and other designers of color. The message was as clear as the styling: Clothes can carry values, widen the frame of leadership, and make space for who gets seen.

Black fashion doesn’t live only on catwalks; it’s stitched into Sunday morning rituals and the idea of “Sunday Best,” where bold suits, coordinated sets, and sculptural hats turn sanctuaries into galleries. It’s carried by models who opened doors — like Donyale Luna, Beverly Johnson, Naomi Campbell, and Bethann Hardison — and sustained by editors like André Leon Talley, who used editorial power to champion Black expression. It’s documented by photographers who made everyday elegance unforgettable, including James Van Der Zee in Harlem and Addison Scurlock in Washington, D.C., ensuring that what might have gone uncredited became part of the historical record.

Keep Reading

-

Vanguard

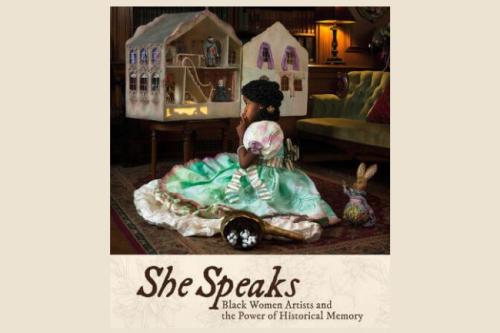

VanguardHoward University Gallery of Art Lends Elizabeth Catlett Works to Major Exhibition on Black Women’s Historical Memory

Jan 30, 2026 3 minutes -

Legacy

LegacyBuilding the Mathematical Mecca: Howard’s Half‑Century of Innovation, Scholarship, and Leadership

Jan 29, 2026 7 minutes -

Find More Stories Like This

Are You a Member of the Media?

Our public relations team can connect you with faculty experts and answer questions about Howard University news and events.

Submit a Media Inquiry