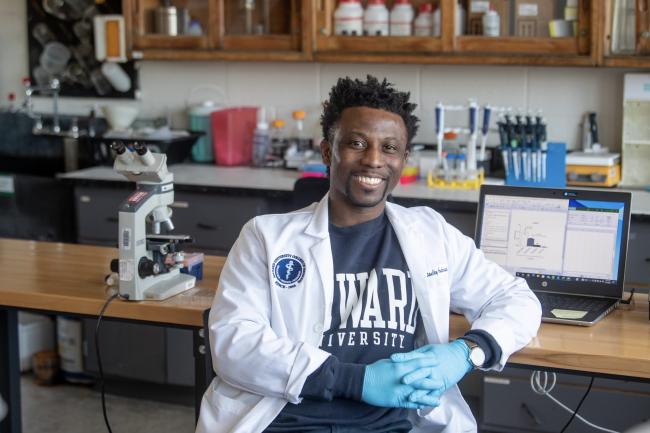

Howard University College of Medicine professor Stanley Andrisse, Ph.D., has achieved what was once unimaginable, rising from a maximum-security prison to tenured faculty at the nation’s only R1-designated HBCU. His journey stands as a powerful testament to hope, second chances, and the transformative impact of higher education.

Q: You’ve gone from a maximum-security prison to becoming a tenured professor at Howard University. What does that milestone represent to you personally?

A: My story represents both possibility and responsibility, and it’s the culmination of years of faith, mentorship, and resilience. But it’s bigger than me. It’s proof that redemption is real — that someone who was once written off as a “career criminal” can stand in front of classrooms, lead research, and shape the next generation of scientists. To my knowledge, I’m the first formerly incarcerated Black man in U.S. history to earn tenure at a medical school.

Q: You’ve spoken about growing up in Ferguson, Missouri, and being labeled a “career criminal” before age 21. How do you think those early experiences shaped the kind of educator and mentor you became?

A: Those early experiences gave me a deep sense of empathy and urgency. I know what it feels like to be dismissed, underestimated, and denied opportunity. As a mentor, I try to be the voice I needed back then. I try to be someone who believes in potential, not perfection. Many of my students are first-generation or underrepresented in science. I say to them: your background isn’t a barrier; it’s your foundation.

Q: What was the moment — or series of moments — that shifted your mindset while you were incarcerated?

A: The biggest turning point was losing my father to his battle with Type 2 diabetes. He slipped into a diabetic coma while I was incarcerated, and I never truly got to say goodbye. That loss broke me open. His battles with diabetes motivated me to read my first scientific article about diabetes. Something clicked. Even though I was physically caged, my mind was free, roaming inside the human cell, trying to understand disease. That spark became my purpose. I decided to live differently and honor my father’s life by pursuing science.

Q: How did pursuing a Ph.D. become part of your pathway out of the criminal justice system?

A: Education gave me access — access to rebuild, to contribute, and to redefine myself. Near the end of my sentence, I applied to six graduate schools. Five rejected me outright. The one that accepted me, Saint Louis University, did so because a mentor vouched for me. That one “yes” changed everything. I earned my Ph.D. in physiology and an MBA in finance, finishing in four years at the top of my class. Education didn’t just change my circumstances; it transformed my sense of self-worth.

Q: You often emphasize that “people are more than their worst mistake.” How did education help you live out that philosophy?

A: Education humanized me again. It helped me see myself not as a number or a case file, but as a thinker, a scientist, and a contributor. It’s what I now try to pass on through my teaching and through From Prison Cells to Ph.D. (P2P), a nonprofit that I co-founded — showing others that redemption is not abstract. It’s something you can live, build, and share.

Q: You founded From Prison Cells to Ph.D. What gap did you see that made you start this organization?

A: When I was released, there was no clear roadmap for someone with my background to enter higher education. Every door came with a lock and a label. I founded P2P to make sure others don’t have to navigate those barriers alone. Since then, we’ve supported more than a thousand justice-impacted scholars nationwide. The goal is simply to move people from conviction to contribution.

Q: You’ve argued that higher education should rethink how it evaluates applicants with criminal records. What do most universities get wrong about “second chances”?

A: Most institutions treat a criminal record as a permanent reflection of character rather than a snapshot of circumstance. They focus on who a person was, not who they’ve become. But overcoming incarceration requires resilience, grit, and focus — the very traits we claim to value in academia. Second chances aren’t charity. They’re smart investments in human potential.

Q: How do you respond to people who still view incarceration as a permanent marker of character rather than circumstance?

A: I tell them that accountability matters, but so does access. You can’t rebuild what you’re never allowed to touch. I don’t excuse my past. I own it. But redemption isn’t about erasing mistakes; it’s about learning from them and using that experience to make a difference. The question shouldn’t be “What did you do?” but “What are you doing now?”

Q: How do your two worlds — scientific research and criminal justice reform — intersect in your work today?

A: They intersect at the point of healing. My lab studies the molecular mechanisms of disease, especially diabetes, while my advocacy work tackles the social mechanisms of inequality. Both are about restoration — of the body and of opportunity. My lived experience makes me a more compassionate scientist, a more grounded educator, and a more relentless advocate. I’m living proof that science and justice can inform one another, that data and dignity can coexist.

###