Most of the time, when people talk about “legacy” and college, they picture generations of families sending their children to the same school, living in the same dorms, and carrying on the same traditions. For Kiona Owens (B.A. ’08), legacy means something different.

“I did not have parents who went to Howard or any HBCU,” said Owens, a D.C. native originally from the Northeast section of the city. “I’m truly the first person in my entire family who graduated from college, and I can see the difference it made in my life.”

A Howard education has also allowed her to move her children into new spaces, enroll them in better schools, and show them that a better life is possible.

Standing along Georgia Avenue during Saturday’s Homecoming Parade, Owens said she makes a point of immersing her two daughters, ages 13 and 16, in HBCU life and culture. This weekend they volunteered at the WHUT FamFest, helping set up tables and participating in different assignments.

While being a first-generation college graduate sometimes feels like carrying her family on her shoulders, Owens says she hopes her journey serves as an example.

“I hope that my perseverance and resilience over the years inspire my kids to want to be part of such a pivotal institution that played a major role in my life,” she said.

Alicia Golliday of Atlanta didn’t attend a four-year college or an HBCU. But this year she’s watched with pride as her daughter Aniya McGary, a first-year criminal justice major, adjusted to life at Howard and thrive as part of the Showtime Marching Band

“My daughter brought me this sweatshirt — a Howard University mom sweatshirt,” Golliday said. “I did not go to an HBCU. I’m actually a nurse. I went to a technical school, so this is really great. I feel proud to raise a child who’s here at Howard University, surrounded by our people.”

She added, “So many people’s children, grandchildren — everyone’s out here at Homecoming, and it’s a beautiful thing. I’m happy she gets to have this experience of being at an HBCU. This will be our family legacy now. She’s a freshman here. She’s in the marching band and plays three instruments.”

For some families, Howard University and the idea of “legacy” mean expanding their HBCU story.

For big sister Kennedy Beavers, homecoming was her first trip to Howard, but it already felt familiar. Her younger brother, Kendall, is a freshman mechanical engineering major and a member of Showtime. Their family traveled 21 hours from Dallas to see him perform in the parade.

“Both of my parents went to HBCUs — my dad to Grambling and my mom to Texas Southern,” she said. “I graduated from Texas Southern, too, so it was important to us that Kendall keep that tradition going.”

Her mother, Janice, says she always wanted her son to be “indoctrinated in the culture” and for him “to experience Black excellence at its finest.”

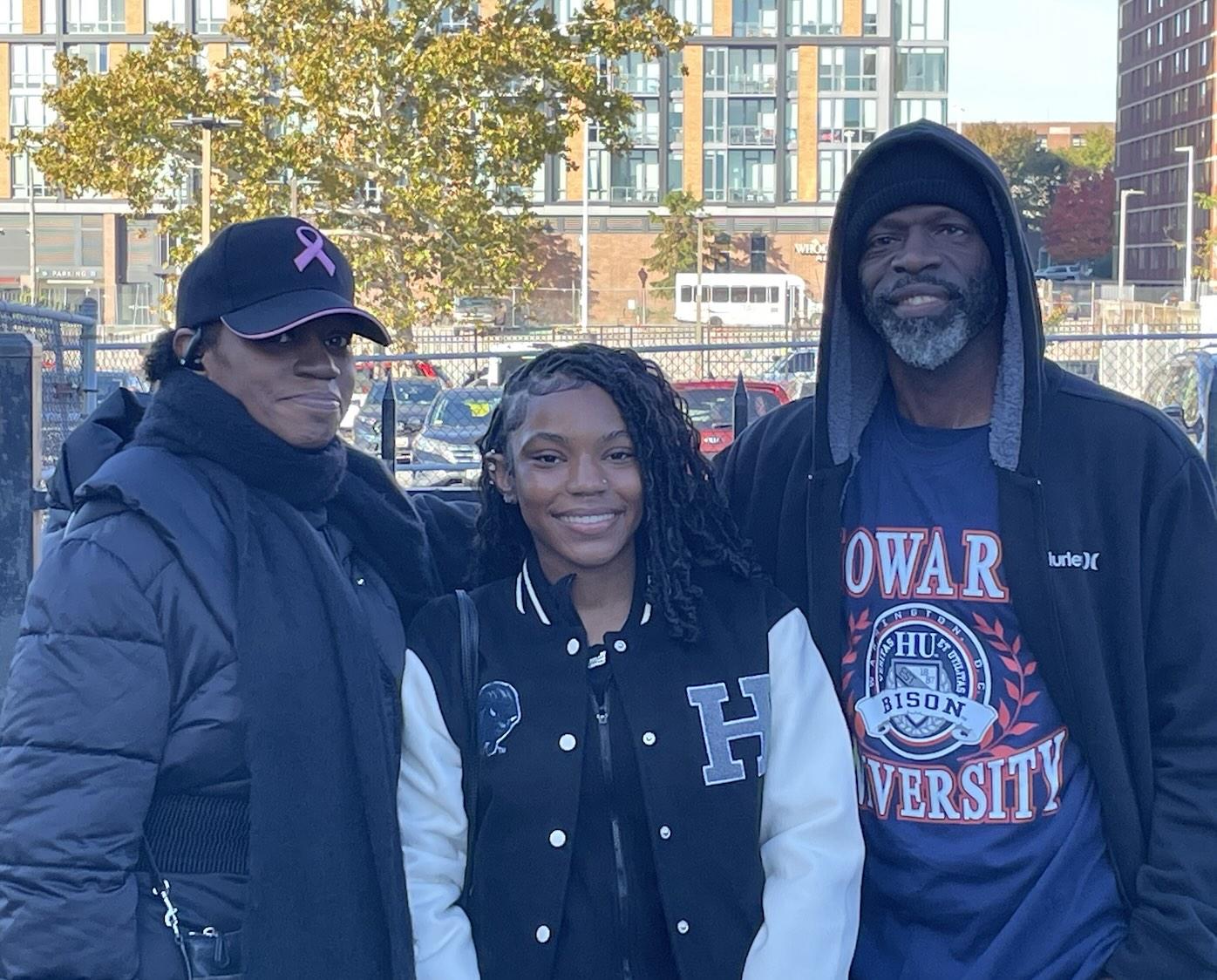

For Kiana Hayes, a first-year biology major from Jacksonville, Florida, a Howard University education means building something new for her family. She hopes to become the first medical doctor in her family.

And there’s likely no place in the world where that dream is more possible than Howard University, which has an unrivaled legacy of training physicians who go on to serve and uplift their communities. Howard also happens to be the nation’s No. 1 producer of African American students entering medical school.

Her parents, Tyson and Catherine Rayford, say they’ve been cheering her on every step of the way from home. “We rep Howard down in Florida. We’re all screaming ‘HU’ down there," Tyson said.

Catherine said their daughter’s journey represents much more than college pride.

“This is going to be the first doctor in our family,” she said. “We’ve always told her she can do whatever she wants to do.”

If Kiana decides against a medical degree, no worries. She can still become a doctor. Howard produces more Black students earning professional doctorates than any other institution in the country. Plus, Howard itself stands as the nation’s No. 1 producer of Black recipients of on-campus doctorates.

###