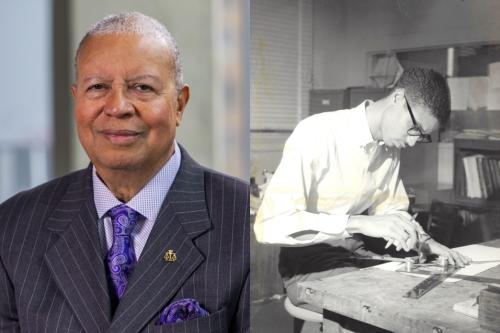

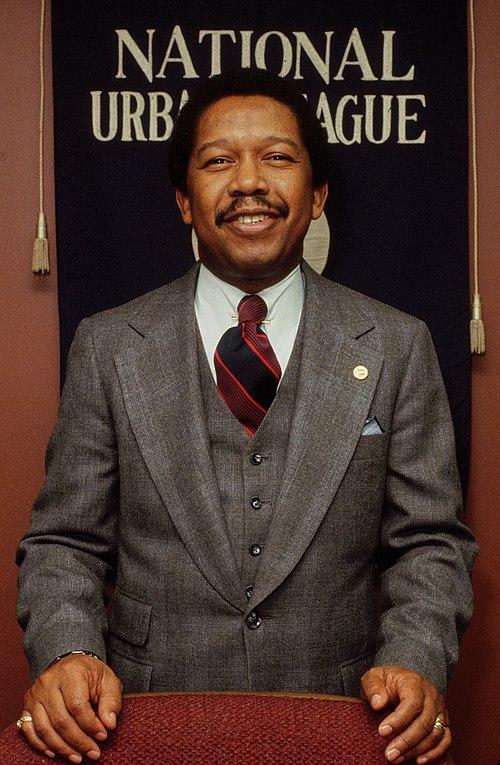

Throughout his life and esteemed career, John E. Jacob (BA ’57, MSW ’63), a former National Urban League president, Howard University alumnus, and Board of Trustees chairman emeritus, has found his greatest successes in building coalitions — and betting on himself.

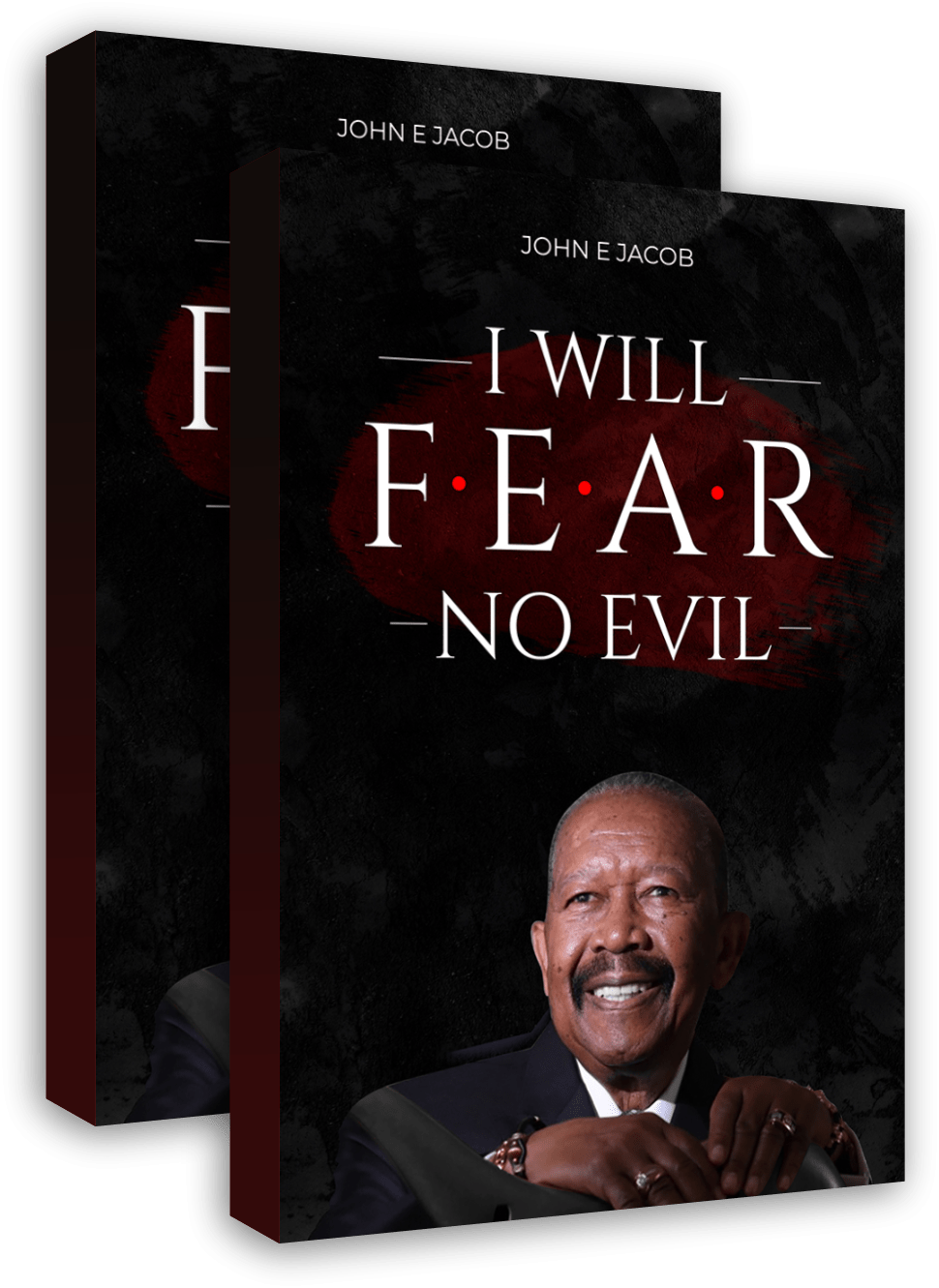

That impulse animates his new memoir, “I Will F.E.A.R. No Evil,” a chronicle of his 90-year journey through segregation, service, and stewardship. Jacob says he wrote it to remind readers, especially Black readers, that the turbulence of the present is not unprecedented.

“We live in some dangerous times,” he reflected. “But we’ve been here before. In my lifetime, I’ve seen cruelty and insensitivity. Black people need to understand that while it is rough and tough, we fought our way through it, and we can do it again.”

For years, Jacob resisted putting his story on paper. His perspective was changed by his wife’s simple plea: “Do it for your granddaughter.” The request unlocked a purpose.

“I grew up when children were seen but not heard,” he said. “I know nothing about what life was like for my parents in the early 1900s. One day, our granddaughter might want to know what life was like growing up in this America during my 90 years on this earth.”

From poverty to possibility

Jacob’s path to Howard began with a decision as pragmatic as it was defiant.

“I grew up poor,” he said. “People see my glory, but they don’t really know my story.”

In his childhood, athletic scholarships were a common ticket to college for Black boys. Jacob assessed his chances candidly — “too small for football, too short for basketball” — and chose a different route.

“I said to myself, you can work at being smart,” he said.

He studied hard with secondhand books from his segregated school and church, earning the top grade point average among the boys in his class. A local white businessman’s scholarship fund for “poor but bright” Black students opened the door, yet the resources would not cover four years at Northwestern University, the only university to which Jacob had applied.

With September approaching and panic setting in, a young counselor at the Houston YWCA, Geneva Bolton (now Geneva Bolton Johnson), sent a telegram to Howard on his behalf.

The reply was swift: “Come on.” Jacob did.

“That changed my life,” he said. “Howard took me in when I had no place else to go.”

The Mecca as a proving ground

The Howard Jacob encountered in the 1950s was, in his words, “truly the Mecca,” a place where extraordinary classmates pushed one another and where, he joked, “we referred to Harvard as the white Howard.”

ROTC sharpened his leadership, while his economics education trained his eye for systems. He commissioned as an Army officer ready to make the military a career, but a recession released many junior officers from active duty. Back in Washington and newly engaged to his Howard sweetheart Barbara (today his wife of 66 years), he scrambled for work – accepting a minimum wage post at a federal warehouse, then passing a special exam to become one of the first parcel-sorting machine operators at the U.S. Post Office.

After nearly two years, a chance conversation steered him to the Baltimore Department of Public Welfare as a case worker, a job he took with a pay cut and loss of federal health insurance with a newborn on the way.

“I couldn’t go home and tell my wife I was that stupid,” he laughed. “I had to figure out how to make this work.”

He did that by centering people. When an older welfare recipient lay down on the office floor at closing time because her check hadn’t arrived, Jacob did the same beside her and bargained for calm, promising that if she went home, he would personally bring the check the next day. Not only did he keep his promise, he also found a way to secure additional support for a granddaughter in her care. He also volunteered to process 11 uncovered caseloads (approximately 300 people) so clients would not miss payments due to staffing shortages.

Jacob’s methods drew scrutiny but, ultimately, support. His dogged approach would convince the department to facilitate his journey to graduate school, a pathway that led Jacob back to Howard for a master’s degree in social work.

Redefining social work and results

While working cases as a graduate student, Jacob received an unusual assignment: a white family whose file was stamped “Do not visit. The man is crazy.” He visited anyway. The man paced and ranted about the FBI; Jacob listened, excused himself safely, then studied the file. The man qualified for disability benefits resulting from his more than 20 years of employment at Bethlehem Steel.

“If he was that disabled,” Jacob thought, “why hasn’t anyone applied for disability benefits?” Jacob filed the claim. Months later the man returned to the office: sharply dressed, grateful, and financially stable thanks to his lump sum award.

“The man wasn’t crazy,” Jacob said. “He was stressed out. People in [social work] are not police protecting the agency. Our job is to reach deep into what’s really bothering people and find a way to help.” He began calling social workers “society’s consultants,” professionals who both diagnose problems and demonstrate solutions.

Building coalitions that change policy

That mindset and work ethic propelled Jacob into Urban League leadership after completing his master's degree — first in Washington, later in San Diego, and ultimately as president of the national federation. The National Urban League, a historic civil rights organization advocating on behalf of economic and social justice for African Americans and against racial discrimination in the United States, is the oldest and largest community-based organization of its kind in the nation.

One early Washington initiative demonstrated his coalition style. Charged with expanding the League’s footprint to Northern Virginia without staff or funding, he began with the local newspaper. An item mentioned white clergy convening in Mount Vernon to discuss “the critical issues confronting Northern Virginia.” Jacob drove to the meeting uninvited.

He challenged the group to confront a basic injustice of both race and economics. Black service members stationed at Fort Belvoir could not find housing near base. The clergy paired Jacob with a Unitarian minister and Air Force veteran, John Wells. Together they met Fort Belvoir’s commanding general and asked him to convene local property owners at the officers’ club. The general delivered a pointed message: Black soldiers defend this nation, and this region’s prosperity.

“Every year Fort Belvoir injects hundreds of millions into the Northern Virginia economy,” the general argued. “Just as we put it there, we can take it out.”

The next day, 1,500 units opened to Black families. Just months later, the Department of Defense issued a nationwide directive enforcing that housing near military installations must rent or sell to Black service members and their families. A local coalition had helped catalyze national policy.

We live in some dangerous times, but we’ve been here before. In my lifetime I’ve seen cruelty and insensitivity. Black people need to understand that while it is rough and tough, we fought our way through it, and we can do it again.”