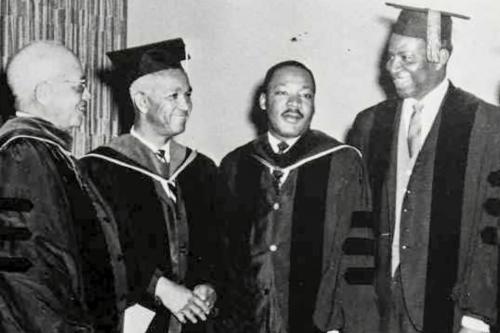

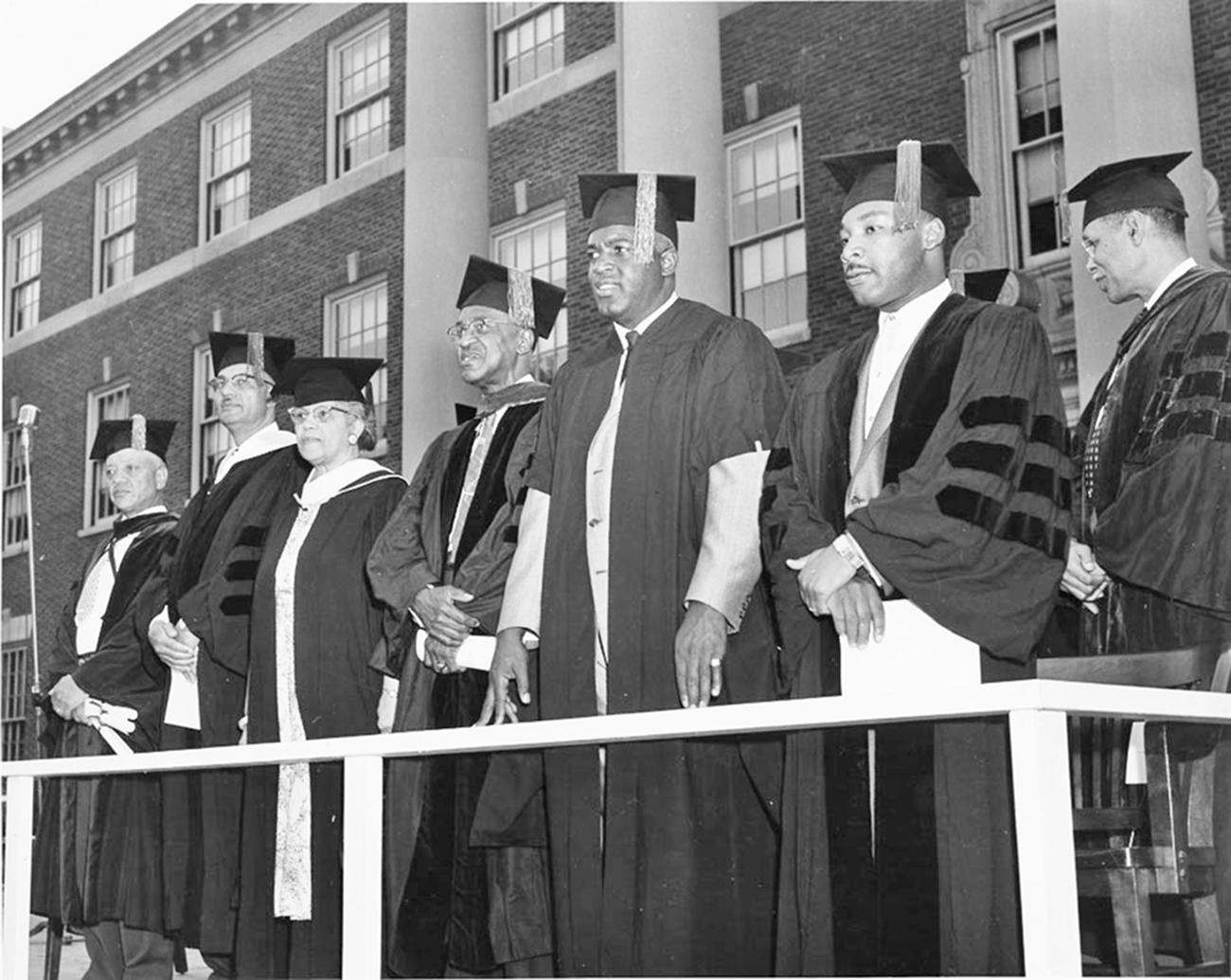

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. inspired countless others through his work with America’s disenfranchised communities. Much of Dr. King’s work energized a generation of students also coming of age during this era, as evidenced by his regular visits to historically Black colleges and universities. Dr. King made several stops at Howard University, which included delivering his first sermon at Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel in December 1956. Months later, in May 1957, Howard bestowed King with an honorary Doctor of Laws degree.

It has been more than seven decades since Dr. King first visited Howard University’s campus, and yet he continues to inspire its students, both in and out the classroom.

Members of Howard University’s Office of the Dean of the Chapel are certain Dr. King’s legacy still permeates the Yard, assisted in large part by its annual Jeremiah A. Wright Spiritual Leader Residency program. Named after Wright, the Chicago-based minister and Howard alum who delivered the University’s MLK Sunday sermon for nearly 40 years, the program is designed to host leaders who will spiritually inspire and nourish the Howard community.

This year’s Spiritual Leader-in-Residence is Teresa L. Fry Brown, Ph.D., associate dean of academic affairs and the Bandy Professor of Preaching at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. Brown’s recent sermons have incorporated contemporary themes such as surviving justice fatigue. In February 2023, Brown presented “The Power of Dreaming Out Loud” as part of a Martin Luther King Jr. lecture series at Wesley Theological Seminary.

“It is appropriate that this takes place during the time that we celebrate the prophetic legacy of Dr. Martin L. King, Jr., who, at the tender age of 26, assumed a leading role in the Civil Rights Movement,” says Dashawn Jones, a graduating senior mathematics major and co-executive director of the University’s Alternative Spring Break program. “Revolutions belong to young adults. Programs like this residency allow young adults to discern our roles in the ongoing struggle for social justice and human rights against the backdrop of political division and violent conflict around the globe.”

Dr. King’s Activism Inspires HUSL’s Legal Scholars

Inside the Howard University School of Law, these future professionals also remain encouraged by Dr. King’s dream.

Jasmine Marchbanks-Owens of Rancho Cucamonga, CA, is a third-year law student specializing in racial justice and lawyering in the social justice movement. A member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Incorporated, Marchbank-Owens wrote the sorority’s legislation that deemed racism as a public health crisis. Her proclamation was adopted by the organization’s national council.

Marchbanks-Owens, also the national vice chair for the National Black Law Students Association, views herself an acting movement lawyer and participates in HUSL’s movement lawyer clinic class. She says the importance of movement lawyering rests in centering those who are at risk, considering few of them can afford the privilege of self-advocacy.

“Movement lawyering is a different way about thinking about the law and helping people,” she says. “You are working directly with the people who are affected, and they are telling you what they want, what they need. They are using us as the legal arm of their activism.”

Marchbanks-Owens believes that Dr. King set a precedent for what lawyering can be through his work of speaking for those in the civil rights journey. She is currently creating a database that identifies every Black judge and clerks throughout the nation. Her philosophy of building larger networks speaks to King’s legacy of pushing generations forward.

"You might not be able to reap the benefit, but the people coming after you are and I think that’s faith,” Marchbanks-Owens says. “Dr. King said faith is taking the first step when you don’t see the whole staircase, and I think that’s movement lawyering is.”

Dr. King said faith is taking the first step when you don’t see the whole staircase, and I think that’s movement lawyering is.”

Fellow law student Harum Al-Hajiz is also inspired by King’s work as a freedom fighter. Al-Hajiz’s legal work focuses on international law and human rights. As it pertains to international freedom, Al-Hajiz calls King a “bridge” during the civil rights movement.

“Whichever side you’re bridging, both sides have to trust you if they’re going to get on the bridge,” Al-Hijaz said. “He may have relied on the church or other avenues, but the law can have the same level of credibility.”

Al-Hijaz recently had a chance to walk in Dr. King’s bridge-building legacy. He and a dozen other law students assisting with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Report 2023. The team examined Black cities facing similar obstacles in achieving equality and evaluated the progress of the community-based organizations and grassroots advocacy groups solving issues in Black communities. Their work was delivered in a presentation entitled “Acknowledging Black America in the Discussion for Sustainable Development Goals: HBCUs Leading the Way” in Geneva, Switzerland.

“We stood on the shoulders of many of other African Americans that attempted to do the very same thing: shine an international light on a very domestic problem,” Al-Hajiz says.

Just as Dr. King was able to highlight American racism on an international level and garner global sympathies in the process, the United Nations trip was an opportunity to broaden universal awareness – a tactic to gain liberation for all oppressed populations, and particularly to hold American systems accountable.

“It’s likely that American isn’t going to punish itself or fix itself without that international pressure,” Al-Hajiz says. “Dr. King was very adept at weaving that thread between communities, not just internationally but domestically.”

Academic Explorations of Dr. King’s Theology

The University honors Dr. King’s legacy through course offerings such as “Theology of MLK,” offered in the School of Divinity. The class curriculum includes Dr. King’s conceptions of God, his religious experiences, and his thoughts on sin and redemption. Students also interrogate the connection between Dr. King’s unwavering dedication to both Christ and his fellow American citizens.

Frederick Ware, PhD, the School of Divinity’s associate dean and a faculty member for twenty years, teaches the graduate level course. “To be a professing Christian is your commitment to being engaged in your community and with society,” Ware says. “That Christian background helped him shape ideas on what the common ground of good is.”

Ware believes today’s depiction of Dr. King has become a cultural symbol, which may alter how people understand the “length and full corpus of King’s work.”

“What I find to be very special about Dr. King, he is not only involved in social activism to deal with the problems in our society, he brings that background, the depth, that activists simply don’t have,” Ware says. “He’s taking the time to read about American history, Western intellect, world history, African history. He’s someone who's a scholar.”

To engage with King’s legacy today, Ware says people should embody King’s belief in American systems such as voting. This rings especially true today as skeptics question the functionality of American democracy during an election year in some of the nation’s most challenging times.

Ware believes affirmative action is another concept that Americans should reconsider, citing Dr. King’s Poor People’s Campaign as an example of affirmative action for equitable class and income distribution.

“King had high optimism in American democracy, to affirm the dignity and worth of human beings, that we develop law and policy to enable people to flourish and live in peace and security,” Ware says. “Given our climate of pessimism, students should be inspired by King’s optimism that you can make these institutions work.”

Given our climate of pessimism, students should be inspired by King’s optimism that you can make these institutions work.”

Bryan R. Parker enrolled in Theology of MLK during the Spring 2023 term and found the class “phenomenal.”

A third-year Master of Divinity candidate, Parker explained that the class analyzes Dr. King through the principles of systematic theology, a philosophy that studies what the Bible teaches about God and His universe by melding those biblical teachings with today’s current events.

“Dr. King was able to unpack those and deliver in very plain-spoken ways that people could understanding, the concepts that people were most gravitate too is the moral arc...that always bent toward justice,” Parker says. “Isn’t that what Jesus was teaching in the Bible?”

Parker says his favorite part of the class was understanding how King became such a “forward thinker” while aiming to build a beloved community. For Parker, Theology of MLK doesn’t challenge the singular narrative of King’s legacy, it enhances it. “We’re pushed to understand more who this man fully is,” Parker says.

It provided a deeper, multi-dimensional look behind Dr. King’s power in activism and how his identities as a Southern Black man, scholar, theologian, and freedom fighter facilitated his rise into an indomitable, international force.

“You understand his early childhood, the impact that had on him moving away and, at a young age, going to college,” Parker says. “[The class] puts a different lens on him because most folks are really aware of Dr. King’s social activism and march for social justice, but they don’t understand that there’s an underlying, systematic theology.”

Dr. King’s ability to draw allies to the civil rights struggle is another major component of his legacy. He was able to talk to all people about the struggle of Black Americans to a worldwide audience, a testament to the power of preaching. Dr. King did not simply stand in the pulpit, he stood in front of the world. Parker pointed to Dr. King’s 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail” as a moment where King, even while jailed, maintained a massive platform to preach his experience to the entire world.

“He reaches out to his fellow pastors, rabbis, ministers and imams, and at that moment he is transcending race,” Parker explains. “He had the credibility to talk across lines.”