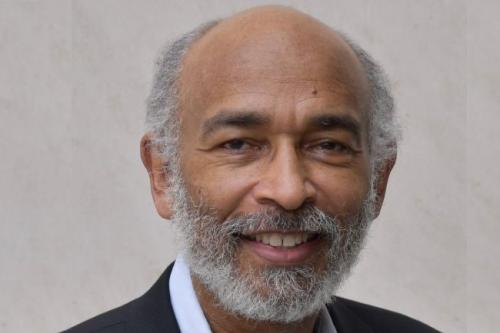

Howard University medical scientist Angel S. Byrd is leading efforts to raise awareness about a chronic skin condition that remains largely unknown to the public but has devastating effects — especially among Black women.

Byrd, M.D., Ph.D., is a tenured professor and the Director of Research in the Department of Dermatology. Byrd and her medical colleagues at Howard University are at the forefront of bringing attention to hidradenitis suppurativa, or HS.

HS is a painful and heavily stigmatized disease that causes inflammation, abscesses, and draining fluid around hair follicles, most commonly in the groin and underarm regions. People with the condition — usually women, and disproportionately Black women — may lose jobs, face rejection from sexual partners, and suffer from a range of psychological burdens. June 1–7 marks Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS) Awareness Week.

“In terms of who gets the disease most, it’s African American women,” said Byrd. “It’s affecting our people, but there is a gap in the field when it comes to Black women and research.”

For Byrd, the urgent and painful experiences of women with HS are anything but abstract. Her research, she said, is driven by the harsh realities Black women face while living with the disease.

“Just imagine being a young woman of reproductive age — how is she supposed to find a mate?” Byrd said. “Some people have dreams of having kids, or just simply would like to wear a sundress or sleeveless shirt in the summer. It’s almost impossible for these women.”

Byrd’s research on the disease was prominently featured in the journal Science Translational Medicine in 2019 and the Journal of Investigative Dermatology in 2025. She served as co–first author on these articles and continues to play a pivotal role in the medical community’s efforts to expand the scientific understanding of hidradenitis suppurativa. She says much of the disease still remains a mystery.

“We do not know why these patients are getting this disease,” Byrd said. “The whole goal is to figure out the why behind this disease. When you understand it, then you can figure out better treatment options.”

Byrd also noted that much of the early research on the disease was conducted overseas, in regions with few Black patients, resulting in limited representation in both clinical trials and basic science studies on HS.

Byrd earned her undergraduate degree from Tougaloo College in Mississippi in 2004. She went on to complete both her M.D. and Ph.D. at Brown University. In 2018, she completed a two-year Ethnic Skin Fellowship in the Department of Dermatology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

When Ginette A. Okoye, M.D. — Byrd’s former fellowship director and longtime research collaborator — left Johns Hopkins for Howard University in 2018, Byrd soon followed. Okoye has been studying hidradenitis suppurativa for more than 15 years, and Byrd joined her research team in 2016. Addressing skin conditions that disproportionately affect Black women has long been a priority for Howard’s Department of Dermatology and the College of Medicine — a commitment underscored earlier this month when Savannah James announced a partnership with the college to test her new skincare line, Reframe.

“Our overarching goal in the Department of Dermatology is to make Howard University the leading resource for training and research in skin diseases that disproportionately affect people with skin of color,” said Okoye.

According to Byrd, HS usually starts around puberty and tapers off around menopause. Current research is examining hormonal influences on the disease, as well as other risk factors such as poverty, obesity, and smoking.

Byrd emphasizes that much more research is needed to fully understand the disease before more effective treatments can be developed. She also notes that the scientific community still has a long way to go in uncovering why Black women are disproportionately affected.

A key goal of Byrd’s research is to increase the number of samples collected from Black women — an effort she says is essential to closing gaps in representation and advancing understanding of a disease that disproportionately affects this group.

“Increasing the number of samples from Black women is the only way to ensure better representation in the science — and with that, we can deepen our understanding and improve how we treat the skin conditions this group is more likely to develop,” Byrd said. “We have a tremendous opportunity to transform the lives of these patients through precision medicine.”

Byrd said there’s still a long way to go.

“If the work is not being done, how can we truly understand it — and how can we effectively treat it?” she said.

###