Howard's annual Research Symposium is the true highlight of the University's Research Month. The research presented by 500 students spanned disciplines, from lunar exploration to biomedical research to the preservation of indigenous and African languages. Despite how varied their focuses were, the researchers shared a common thread — a desire to conduct research with real-world impact, reflecting a dedication to truth and service.

The below students reflecting on their work represent just a fraction of Howard’s next generation of researchers, who are driven to make a positive, tangible impact on the world.

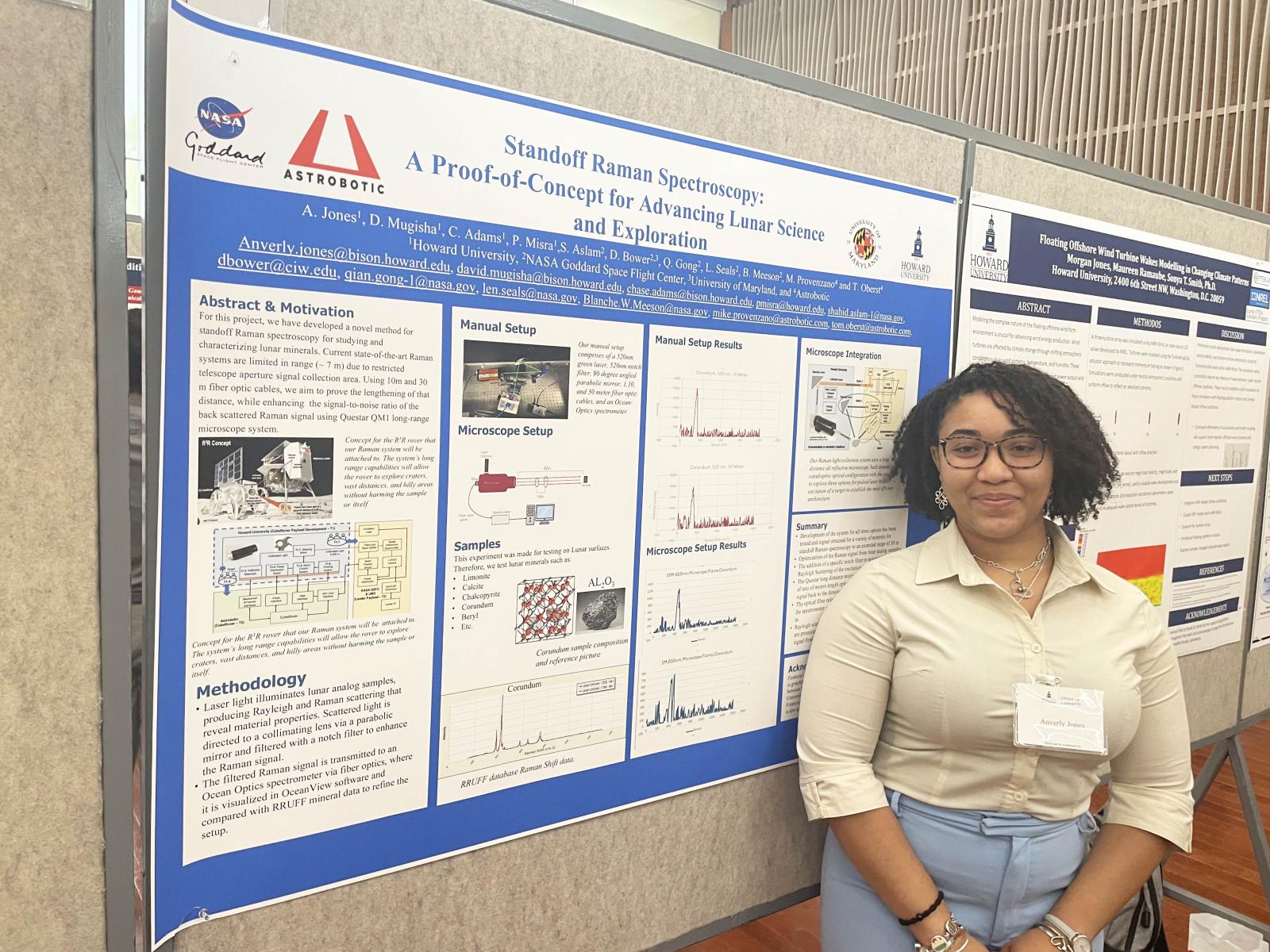

Standoff Raman Spectroscopy: A Proof-of-Concept for Advancing Lunar Science and Exploration

Since high school, junior computer science major Anverly Jones knew she wanted to work for NASA. “Looking for schools, I googled ‘NASA projects with Howard’ and emailed the first contact that popped up.” She’s now spent the past three years working on improving the laser equipment scientists use to collect lunar data. Current methods, known as Raman spectroscopy, have a range of about 7 meters. Jones’ lab is working to prove that distance could be expanded tenfold, greatly increasing the amount of lunar data that can be collected.

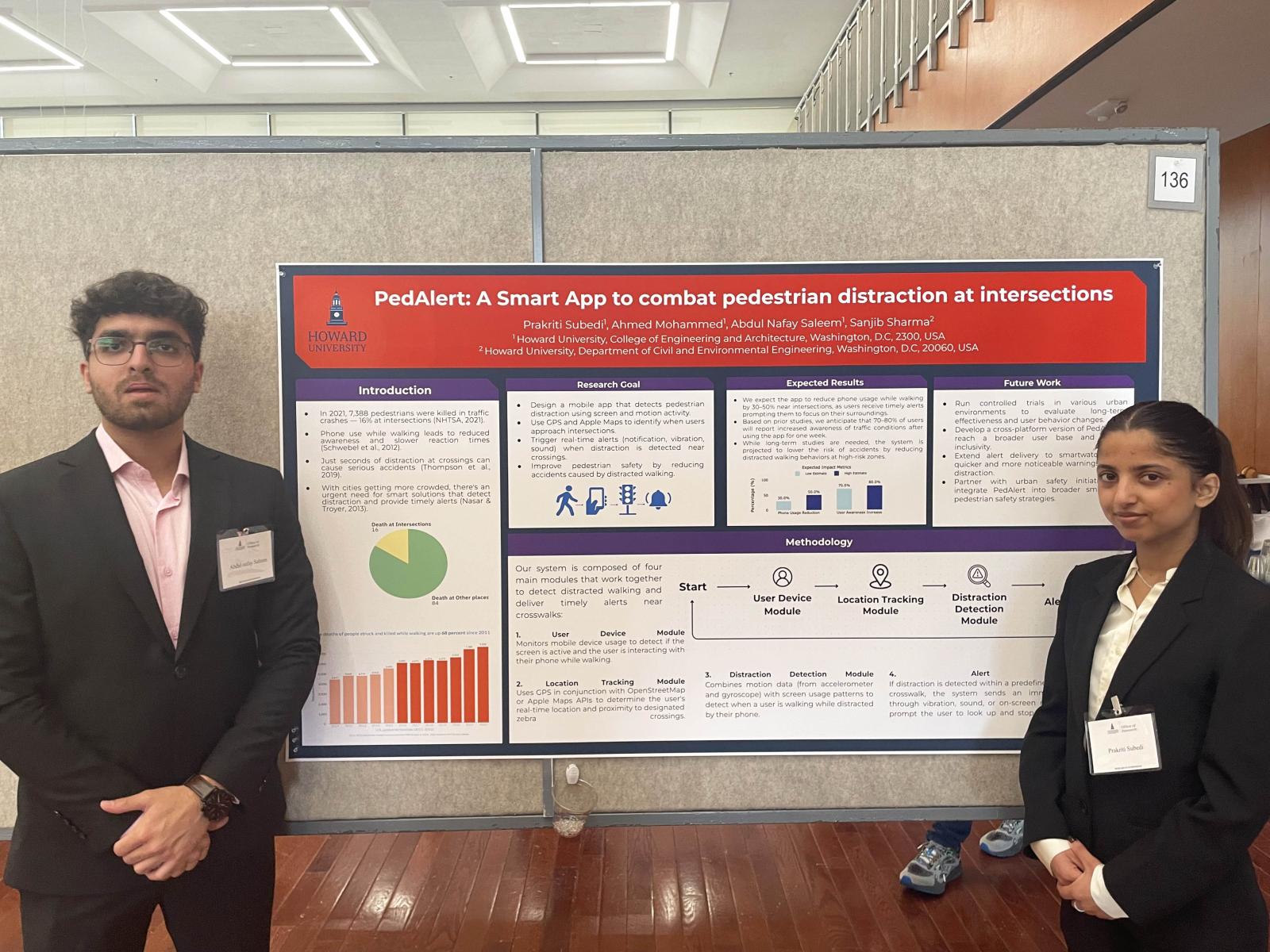

PedAlert: A Smart App to Combat Pedestrian Distraction at Intersections

The inspiration for computer science majors Abdul Nafay Saleem and Prakriti Subedi was a bit closer to home. “We live on campus at Howard, and there’s this intersection at Georgia Avenue and it is filled with cars and it’s very busy,” Saleem explained. “There’s a lot of pedestrians there, and on a daily basis we see near accidents.”

To help prevent the over 7,000 pedestrian deaths per year, they designed PedAlert, an app to alert users who may be distracted by their phone when they are approaching a busy intersection. “If we can bring that number down even just by 500, we’re essentially saving 500 lives.”

Haptic Feedback for Tonal Language Learning: A Culturally Responsive Approach to Preserving Linguistic Diversity

Sophomore computer science major Kamili Campbell was driven to limit biases in AI and language processing tools after studying how underrepresented African American English is in the field. Even further, these tools focus on only a small fraction of the world’s languages, a gap that not only leads to inequities in using these technologies but makes it more difficult to preserve smaller or tonal languages, such as the West African Yoruba language.

“Historical memories and cultural significance, words of wisdom, prayers, songs, games, all of that can only really be passed on if you know the mother tongue,” explained Campbell. In her research, she and her colleagues attempted to simulate the tonal rhythms of Yoruba through haptic feedback in a regular video game controller, potentially creating an immersive way to learn and preserve the language.

Breaking Stereotypes: How Gender and Racial Bias Shape Caregiving and Childrearing Expectations

School of Education doctoral student Zipporah Lewis focused her research on racial and gender biases that shape childrearing and caregiving, looking at the stereotypes and learned behaviors that lead fathers to have negative feelings toward caregiving roles and make them less likely to seek support. Lewis was first inspired to study this issue as a child, when her father played a highly active, supportive role after her diagnosis with dyslexia, and she noticed how many people did not share her experience.

She hopes her research will help serve as a call to action to spark discussions in schools, communities, and workplaces about the portrayal of caregiver roles, and support policies that provide support for all caregivers, emphasizing the need to start small and locally.

“Are there social support groups? Are there Facebook support groups? A lot of doctors actually give referrals for support groups for families, saying ‘hey, this might be helpful for when you’re going through certain things,’” Lewis shared. “It’s so important to make sure that the things that are being put out are targeted to specific groups, not to say that overarching support isn’t helpful, but when I see someone that looks like me in a support group it helps me feel more comfortable with being able to return.”

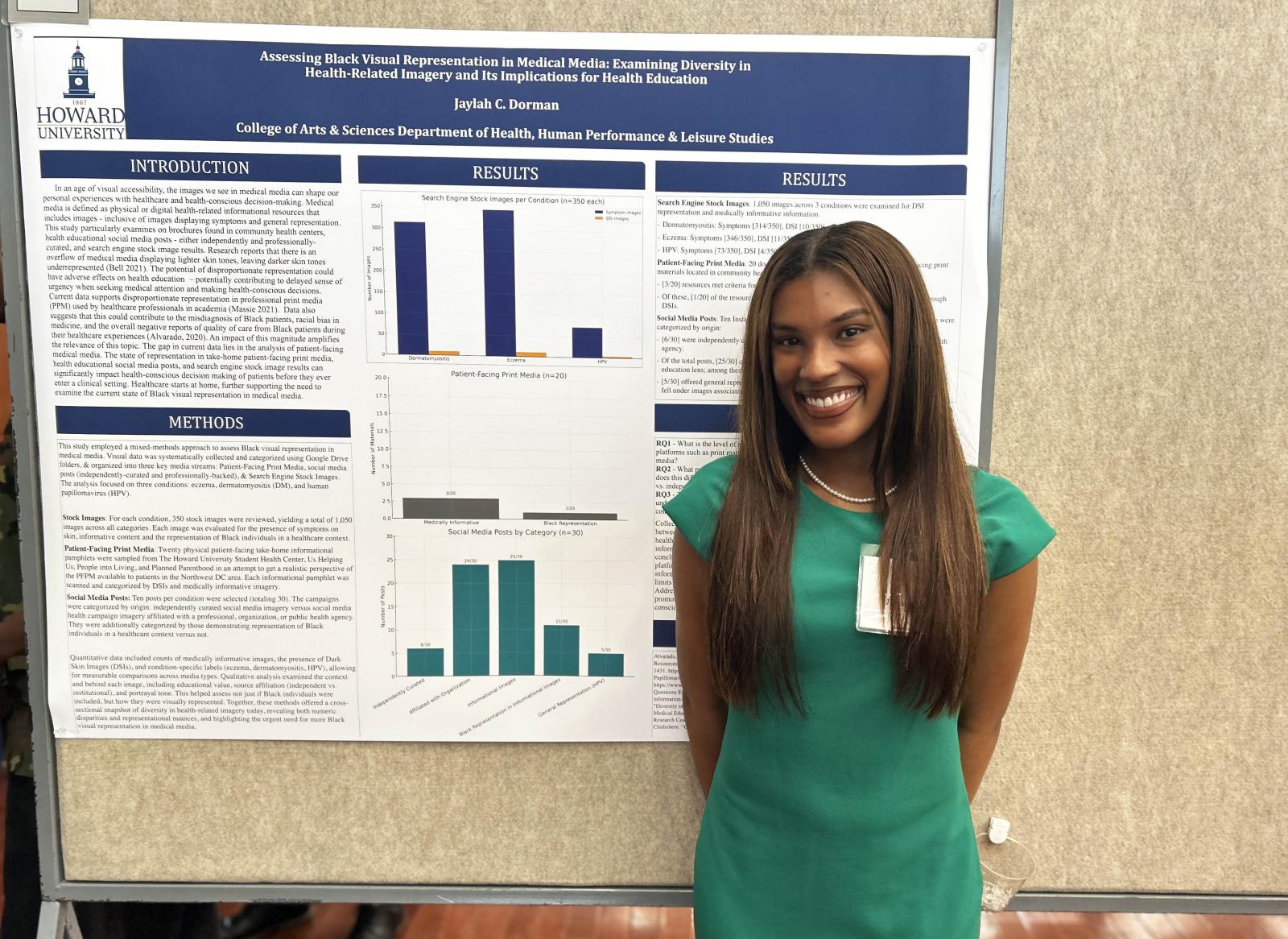

Assessing Black Visual Representation in Medical Media: Examining Diversity in Health-Related Imagery and Its Implications for Health Education

“My research acknowledges that there are gaps in the data surrounding medical media. We see a lot of what is being produced as far as the impact it has on physicians being able to diagnose properly, and unfortunately, it’s not very favorable,” said Jaylah Dorman, a graduating senior health education major with a concentration in community health and a minor in chemistry.

Defining medical media as any imagery that you see in a healthcare context, Dorman’s research examined the implications of a lack of representation of those with darken skin (referred to as “Dark Skin Images” or “DSIs”) on health education and included examining the number of medically informative images available across three platforms. She looked at available stock imagery online via Google, patient-facing print media from the Howard student health center, and social media posts via Instagram, focusing on images related to eczema, dermatomyositis, and HPV. She found that Black representations, even for conditions that had adequate general imagery, fell flat or below that of other communities across the three mediums. “We need resources that are physically helping us and being reflective of who we are and what we’re going through in a healthcare setting.”

That said, Dorman was surprised to find more informative DSI representation via social media, indicating that the community is stepping up to make sure they are seen in this context. “There’s a lot of impact happening through social media,” she said. “Twenty percent of the medical media on social media was independently curated, which means that people were reclaiming their power for what they saw on Google and through print media and decided to curate their own content.”

Social media also proved to include more informative imagery featuring the Black community, further demonstrating its usefulness as a tool to increase Black visual representation in medical media. “As far as Black representation, over 30% of the images represented Black people in an informative way, versus the less than 1% and 5% for medical media and Google.”