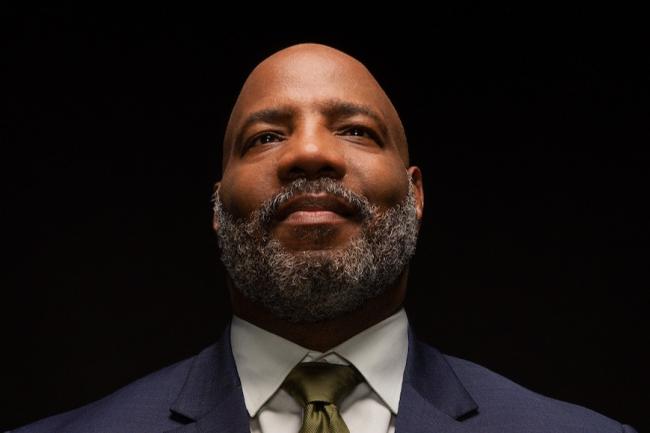

During this year’s Charter Day exercises, Howard University will honor Jelani Cobb, Ph.D. (B.A. ’94) with its annual Alumni Award for Distinguished Postgraduate Achievement, in recognition of a journalism career built on intellectual rigor, cultural fluency, and an unwavering belief in a collective truth.

Cobb’s résumé is as illustrious as it is varied: a writer who has helped the nation make sense of race, politics, and power; a documentarian who brought the stakes of voting access into homes and classrooms nationwide; a scholar who moves deftly from Reconstruction to hip-hop; and, since 2022, the dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, one of the most prestigious placements in American if not global media. He has also authored critically acclaimed works, including 2007’s “To the Break of Dawn: A Freestyle on the Hip Hop Aesthetic,” 2010’s “The Substance of Hope: Barack Obama and the Paradox of Progress,” and 2025’s “Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here: 2012-2025.”

But Cobb’s approach to journalism was forged much earlier, right here at The Mecca. If you ask him where the foundation was poured, he does not hesitate.

“With the exception of my family,” Cobb said, “no other institution has had as much of an impact on who I am as Howard. It’s my parents, my siblings, and then Howard.”

Becoming Jelani

Cobb arrived at Howard in 1987 and was immediately immersed in a campus environment that would sharpen his worldview. He described those early days as a prompt reorientation to history from a vantage point he had not previously been taught.

“What I learned very quickly,” Cobb recalled, “was the importance of the viewpoint that had been left out; that you only know half the story.” The version that rises to the surface, he added, is often “politically beneficial to the victors or the people who wrote it.”

He especially credited a course titled “Black Diaspora,” taught by the late Howard professor Adell Patton Jr.

“Professor Patton really set me on my course,” Cobb said. “The things that I’m doing now are largely a product of his influence and that class I took when I was 18 years old.”

He also cited Dr. Elizabeth Clark-Lewis, another influential member of Howard’s history faculty, as a valued mentor. Reflecting on their guidance, Cobb spoke lovingly of their belief in him that extended beyond encouragement, an almost prophetic sense of who he could one day become.

“It’s very important that you have people in your life who can see things in you before you can see them,” Cobb said. “When I would do things in my career, I’d be shocked, and my mentors weren’t because they saw that for me long before I could see that for me. I think that the best part of the story is that I get to do that for other people now.”

While that initial foundational shift was academic, it was also deeply personal. During his time at Howard, Cobb changed his middle name from Anthony to Jelani, which translates to “full of strength” in Swahili. He would also join his classmates in occupying administrative buildings to protest apartheid and the appointment of politico Lee Atwater as a university trustee.

If those years sharpened Cobb’s instincts, they also clarified his commitments. Howard did not teach him to chase proximity to power — instead, he had learned to scrutinize it.

“What I took from Howard was the importance of being able to tell the story of your community, how you experienced history, and what your impact had been on shaping that history,” Cobb said.

A Writer Shaped By Culture

Cobb’s understanding of voice, rhythm, and narrative began with hip-hop. He grew up steeped in the culture as it was taking shape across New York City in the 1970s and 1980s.

“I learned to write by writing raps,” he said matter-of-factly. “That was my path into writing. Long before I was writing books or essays or columns, I was writing rhymes.”

For Cobb, the supposed juxtaposition of hip-hop scholar and dean of Columbia’s journalism school doesn’t feel contradictory. If anything, he sees hip-hop as a case study in invention under constraint: what happens when communities are denied resources and still create new practices. He recalled how music programs were cut from New York schools, and how critics once dismissed the emerging sound as “not music.”

“That is what music would sound like for people who you denied the ability to learn how to play instruments,” Cobb said. “We’re going to take that and turn it into high art. That is genius. We never grapple with the level of artistic and creative brilliance required to do that.”

Long before I was writing books or essays or columns, I was writing rhymes.”

Cobb’s professional career followed a similar origin story, rooted in Black institutions. Before joining The New Yorker as a staff writer in 2015, he wrote for “lots of small publications, lots of Black publications.” He traces a critical beginning to an internship at ONE magazine, a local D.C. publication founded by Howard alumnus Eric Easter (B.A. ’83).

“I had been learning how to cover politics, how to give context to current events by using history, and those had been the laboratories where I really started developing those skills,” Cobb said.

When he began contributing to The New Yorker in 2012, his first topic — amidst Barack Obama’s presidential reelection campaign, no less — was Trayvon Martin. Looking back, Cobb sees Martin’s death as a spark that accelerated what followed. By the time Cobb became a staff writer, the moment demanded not just commentary, but historical clarity.

“We couldn’t know it at the time, but in many ways, Trayvon Martin’s death became the impetus for all of the things that came after, in terms of Black Lives Matter, social justice movements, all the things that really culminated with what you saw with George Floyd,” Cobb recalled. “That was why it was important to be doing that work at that moment.”

A similar impulse animated the inception of his 2020 Peabody-winning PBS Frontline documentary, “Whose Vote Counts.” In the wake of judicial revisions that weakened the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Cobb suggested to colleagues at Columbia that they cover “access to the ballot box” during the 2020 presidential election, particularly in locations where results may be close or contested.

Then, without warning, the COVID-19 pandemic struck. While the new restrictions forced an inconvenient pivot in how they completed the film, the pandemic fortuitously became a crucial portion of the narrative arc. The film, Cobb explained, became particularly urgent because of how these forces converged at once.

“It wasn’t until later that we realized that the pandemic was part of the documentary, because it might provide a rationale for people to create policies that inhibited communities, particularly Black and Brown communities, from being able to get to the polling places,” he said.

“All of those things came together as we were working on the project, and we knew it was going to be important because of the timing of it.”