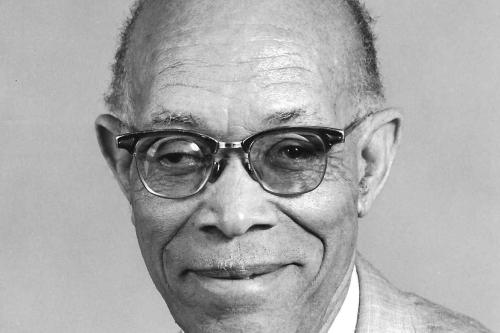

In a 2012 feature story written by the Washington Post’s John Kelly, an 88-year-old Roland Maurice Jefferson (B.S. ’50), a D.C. native, remembered a fond childhood memory. Eighty years ago, his father took on a a trip to the National Mall to see the cherry blossoms for the very first time at the age of eight years. It became an annual trip, a sweet reminder that satisfied his need to know more.

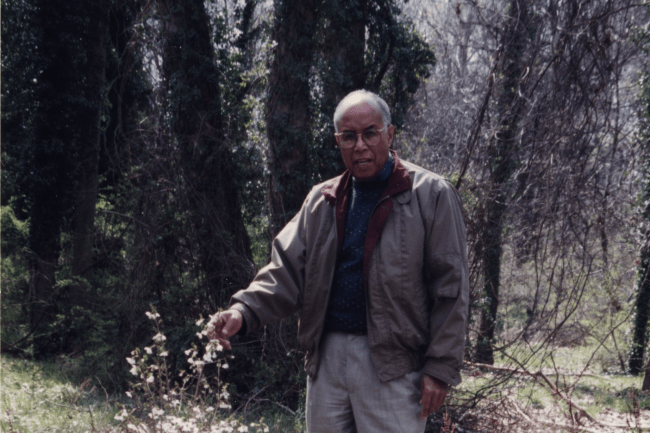

It marked the beginning of a lifelong journey of achievement, innovation and success for Jefferson. He’d go on to become the National Arboretum’s first Black botanist as he created innovative strategies to sustain the beloved flowers gifted from Japan.

His main work prioritized creating innovative methods to ensure the right propagation of cherry trees, a method to breed plants naturally. According to the National Agricultural Library, Jefferson’s findings span from 1961 to 2006.

In 1909, Tokyo’s Mayor Yukio Ozaki and First Lady of the United States, Helen Herron Taft agreed on a cultural donation of 2,000 cherry trees from Japan to the U.S. However, the trees wilted on U.S. soil since the officials were not equipped with the best practices of sustaining the cherry trees. A second set of approximately 3,000 trees were replanted in 1912. Scientists were appointed to the United States National Arboretum to avoid destruction.

After graduating from Dunbar High School and serving in the United States Air Force, Jefferson attended Howard University on the GI Bill. He earned a Bachelor of Science in botany from Howard University in 1950.

In 1956, Jefferson officially became the first Black botanist to develop advancements for the trees within the ever-changing climate of the nation’s capital. His main work prioritized creating innovative methods to ensure the right propagation of cherry trees, a method to breed plants naturally. According to the National Agricultural Library, Jefferson’s findings span from 1961 to 2006.

Jefferson complied historical, scientific data about the replanted Japanese cherry trees in Potomac Park. He published the “Japanese flowering cherry trees of Washington, D.C.” research in 1977, detailing his findings of his work which maintained the growth and health of trees nearly 80 years after their replanting.

The impact of his work stretches beyond the US. In 1978, Jefferson participated in a year-long trip to Holland, England, and Germany to study cherry and crabapple trees. In 1981, he adapted his research findings into lectures about cherry trees for the Japanese government, eventually conducting more research in collecting and evaluating hundreds of tree species throughout Japan.

Outside of the research room, Jefferson spearheaded programs between Japan and the U.S. centered on the wellbeing and cultural significance of the trees. In 1982, Jefferson created a seed exchange program between Japanese and American school children. In partnership with the Flower Association of Japan, over 500,000 American dogwood seeds and Japanese cherry seeds were swapped during the year-long program with thousands of elementary school students from New Jersey, Missouri, Texas, North Carolina, and Virginia participating in the project.

Among his programs, innovation, research and international studies, Jefferson fortified his position as an international authority on flower trees and retired from the United States National Arboretum in 1987, though he lectured on his findings until 1998.

Many of his innovative findings are archived in the National Agricultural Library in “The Roland Maurice Jefferson Collection.” Though the beloved cherry trees face modern climate issues, Jefferson’s historic findings in propagation innovations are still implemented today. On November 27 2020, Jefferson died at the age of 97.

As the nation's capital prepares for this Spring’s iconic National Cherry Blossom Festival, remember: this is a Bison’s work to be embraced by the world.