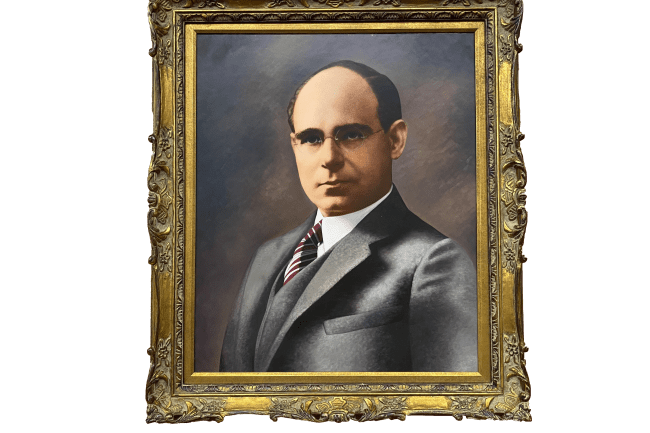

Johnson, meanwhile, feared that a Black president at Howard University was bound to suffer due to what he described as “internal difficulty which threatened the life of the institution.” Despite his feelings, a unanimous trustee vote for Johnson’s presidency convinced him to accept the position. The unwitting first Black president of Howard University brought the institution into national prominence.

Born in Paris, Tennessee on January 4, 1890, Johnson was known as a prankster during his early years. Wanting their son to receive his education at a Baptist institution, Johnson’s parents sent him to Atlanta Baptist College, now Morehouse College, for his high school and college education. Johnson’s grades were consistently outstanding, but he got into so much trouble that John Hope, the first Black acting president of Atlanta Baptist College, wrote a letter to Johnson’s father. Johnson cleaned up his act until his junior year of college, at which point he was suspended for playing cards—a major infraction that was prohibited at missionary-founded schools for Black students.

Following his suspension, Johnson returned to his studies and graduated with high honors. He was hired at Atlanta Baptist College, where he served as an instructor for five years. Afterward, he taught at the University of Chicago, where he earned a second Bachelor of Arts degree.

By the time Johnson was tapped for the position of Howard University president, he had also earned a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Rochester Theological Seminary, a Doctor of Divinity from Harvard Divinity School, and a second, honorary Doctor of Divinity awarded to him by Howard University in 1923. Part of Johnson’s reluctance to become Howard University’s president was a result of the honors he received under Durkee’s leadership; in addition to the honorary D.D., Johnson was the principal speaker during the annual Week of Prayer at Howard University for five years in a row.

Johnson’s vision for the University emphasized the need for Black lawyers and educators. He referred to sociology, economics, social philosophy, history, biology, anthropology, and religion as the necessary intellectual resources for the advancement of Black Americans and the United States as a whole. In keeping with that vision, Johnson strengthened the University’s facilities and faculty, seeking to build up the University to compare favorably to any liberal arts university in America.

Improving the University’s financial status was Johnson’s first order of business as president. Since 1879, Congress provided subsidies to the University, but the amount of money provided was neither adequate nor annually guaranteed. Encouraged by Johnson’s leadership, representative Louis C. Cramton and other lawmakers pushed a law through Congress that provided annual support. In recognition of this monumental 1928 act, the NAACP awarded Johnson with its highest honor, the Spingarn Medal.

Under his 34-year administration, Congressional appropriations to the University increased to $6,000,000 annually, the number of faculty tripled, faculty salaries doubled, and the quality of each school in the University improved.

Notably, Howard University’s College of Medicine, one of two medical schools in the country that accepted Black students, obtained a $250,000 grant for a new building, plus $180,000 for equipment. The School of Law went from a night school to the premier training grounds for Black civil rights attorneys and law professors, including future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. National honor societies, such as Phi Beta Kappa, were established on Howard University campus. Enrollment increased exponentially.

Johnson continued to be an active public figure following his retirement in 1960. He spoke out against United States militarism during the Cold War and advocated for economic aid and political development in Third World nations. By the end of his life, Johnson, the son of a former slave and a domestic worker, found his way from little Paris, Tennessee, to the nation’s capital, becoming a prominent and sometimes controversial public figure who inspired Martin Luther King, Jr., and was praised by then-senator John F. Kennedy. Johnson’s impact on the University remains palpable today—a fitting legacy for the first Black president of Howard University.