“I don't believe in magic, ghosts, or demons. Just power.”

— Smoke (played by Michael B. Jordan)

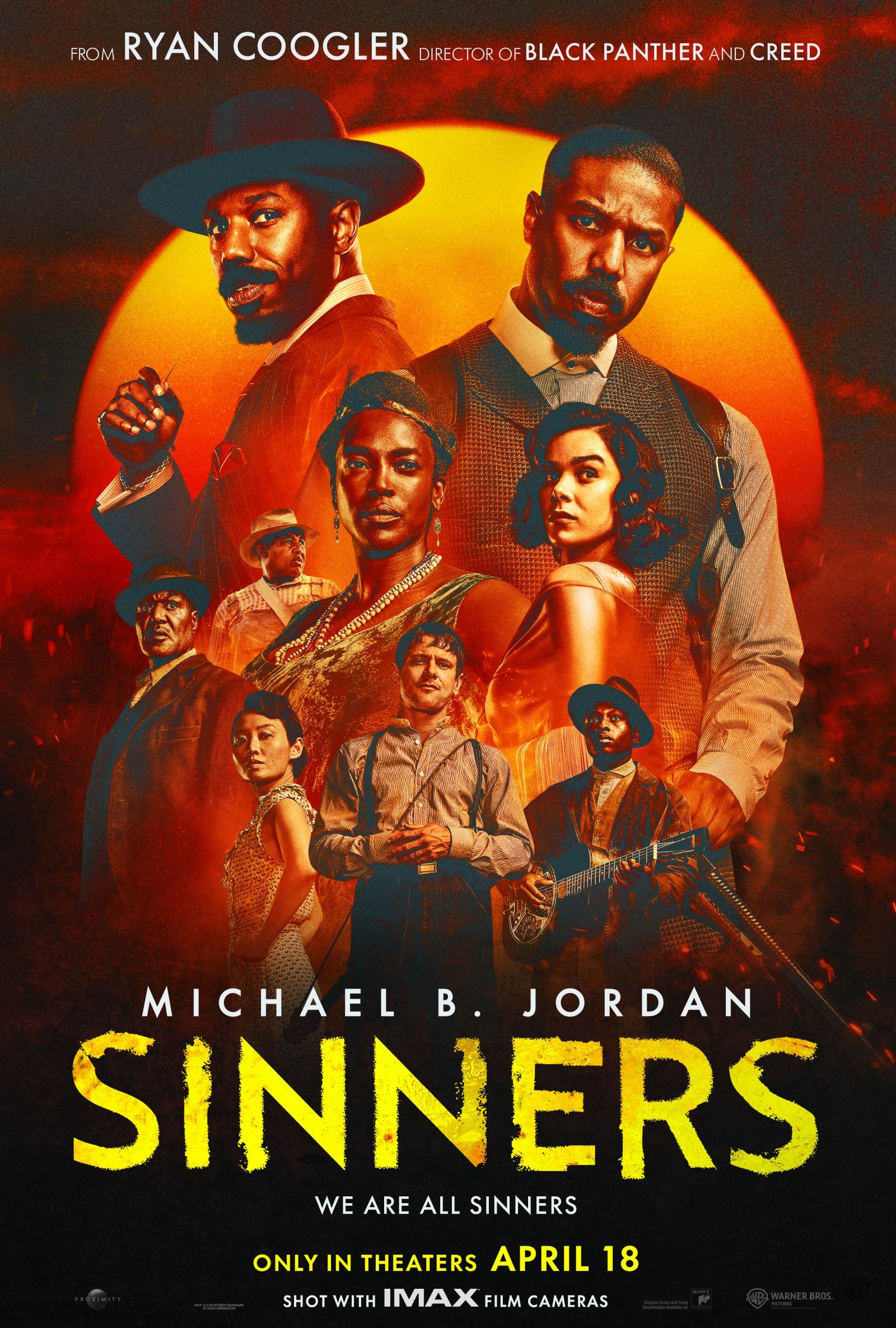

At first glance, Smoke’s declaration sounds like a rejection of both Christianity and hoodoo. But perhaps the true “power” in “Sinners” is not supernatural at all, it’s the humanization of a region too often caricatured or dismissed. The Deep South, despite its rich cultural legacy, is frequently viewed as an embarrassment — a place where progress stalls, dreams die, and history is remembered only for its violence toward Black folk and other marginalized groups. In “Sinners,” set in Jim Crow-era 1930s Mississippi, Ryan Coogler takes us beyond that narrative. Through a supernatural lens, he tells a story where the real magic is survival itself, and that despite everything, Black southerners persisted. And, well, sinners have souls too.

I grew up in the Lowcountry, along the stretch of I-95 South that hugs the Atlantic coast. It’s known for Gullah Geechee sweetgrass baskets, fresh seafood, saltwater marshes, and the prized “Carolina Gold” rice. But it's also known as the “Corridor of Shame,” a term born from the run-down and underperforming schools in the area that often function more as holding pens than places of learning, preparing kids not for college but for prison (a la the school-to-prison pipeline), or for premature death, memorialized on air-brushed t-shirts. All of this exists alongside still-standing plantation homes, slave shacks, and never-ending winding country backroads where strange fruit once hung from trees.

It’s the kind of place people imagine when they think of the “old South,” a region many outsiders see as frozen in time for all eternity, backwards, ignorant, and out of step with the rest of the country.

That’s what made “Sinners” such a revelation.

The Southern gothic horror movie takes place in 1930s Mississippi, an era immediately following the “Roaring 20s” when instead of jazz and showtunes, Black people were singing the blues. As a self-proclaimed critic of Hollywood and its obsession with remakes and Eurocentric mythology, I admittedly didn’t pay much attention to the film at first. It wasn’t until I read the synopsis that something clicked, and I felt seen, as well as heard. A horror movie set in the Deep South, hoodoo, saints, “haints,” and Michael B. Jordan? You know the vibes!

I grew up hearing stories about “the hag” warned she’d take me on a ride if I misbehaved. I was raised in a double-wide trailer painted “haint blue,” destroyed by a thunderstorm last semester (shades of the scene where Smoke asks Annie why her magic didn’t protect their baby). My mother, deeply religious, once prayed I wouldn't be born on Halloween, “the devil’s holiday.” (She eventually gave in and let me trick-or-treat; maybe her prayers worked, because I came 10 days early.) In short, this film wasn’t just entertainment, it was a story that spoke to me.

Now I was very interested — even if only to see if Coogler, hailing from the California Bay Area, could really capture the soul of the South without falling into the usual traps. Would this be yet another portrayal of “country cousins” used for comic relief? Another “South bad, North good” trope so much of Hollywood (and society) falls into? You know the trope I mean; the “ignorant,” “‘po,” and simple cousins go up North or travel West for a family reunion or Grandma’s passing, as that’s the only time the other side of the family engages with ‘em because they’re so far removed from the Southern roots that grew their tree — from recipes that were preserved to the customs and traditions we still hold onto.

Here were characters who looked like me, sounded like me, and came from a background that mirrors my own.

To my surprise and genuine emotion, it wasn’t.

From the opening scenes, I was locked in. Here were characters who looked like me, sounded like me, and came from a background that mirrors my own. A world I recognized, not as stereotypes, but as fully realized people and human beings. Not just slaves or servants, but complex Black men and women trying to live, not just survive. People who carried grief, loss, anger, and oppression, yes; but also, joy. They danced. They mourned. They were people who had strong ties to Christianity but still held onto their Africanisms as it took new forms in hoodoo, root work, or the more popular and well-known vodou. They enjoyed letting loose — or, as they said back then, “cuttin’ a rug” — at the juke joint that was just as hot as the grease Annie fried her fish in.

Far too often, when movies take place in the South, beautiful landscapes such as the iconic Southern magnolia trees and coastal beach landscapes serve as merely a backdrop to the story. And it’s a story that tends to stem from the misrepresentation of the region and the people who call the South home. Ever heard of Gullah Gullah Island? To many, it was a tropical paradise in some far away, exotic land. But for me, it was only a hop, skip, and a jump away on St. Helena Island, a cultural hub nestled in the rural neck of South Carolina. The idea that the South is inherently deficient — pretty on paper but a mess in-between the lines, meaning the only way to become “rich and famous” or successful is to leave and never look back — isn’t exclusive to the white filmmakers and screenwriters of Hollywood. In fact, one of my favorite movies, “Daughters of the Dust,” directed by Julie Dash and filmed on St. Helena Island, features fictional Black characters that moved to New York City, only to turn their noses up at their kin back home. Again, “Sinners” bucked these stereotypes.

In the film, Mississippi is not just a site of pain, but of culture and resilience. The same state tied to the Confederacy, the disenfranchisement of African Americans during and after slavery, the Indian Removal Act, and endless stereotypes about illiteracy and ignorance, becomes something richer, more profound. The film reveals a powerful truth: There is magic in being Black and Southern, and in the rich ecosystem of the Mississippi Delta. There’s magic in the food, the music, the land, and the spirituality. It's an ecosystem of survival, and despite everything, we persisted.

And yet ironically, despite all of this, Clarksdale, Mississippi, where the movie takes place, doesn’t even have a movie theatre to see the story inspired by them, residents having to fight for access to the film.

So much for “by us, for us,” right?

But still, “Sinners” exist. It dares to imagine a version of the South where dignity coexists with wickedness, where the horrors of history don’t eclipse the beauty of Black life, and where the so-called “sinners” turn out to have the most powerful souls of all.