Since 1994, the Howard University Alternative Spring Break program has been a prominent – and growing – presence on campus, offering students another means of reenergizing themselves ahead of the final month of the semester. To be sure, HUASB can be physically exhausting, with hours spent traveling and early wake-up times to get students out of bed before 6 a.m. But the program is designed to be just as restorative, if not more so, than a relaxing vacation or a week spent lounging at home.

“Service is good for your mental health,” says Sandra Crewe, dean of Howard’s School of Social Work. She has been involved with HUASB for more than 20 years and has traveled with students through the program to places like New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. She talks about the importance of serving in a manner that feels authentic and uplifting, not only for the people receiving support, but also for those who are giving it.

“If service becomes a burden, then that’s no longer service,” Crewe says. “Service is given with a free spirit of wanting to help and wanting to make a difference in one’s life.”

HUASB and other service projects organized by the Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel are oriented around the rhythms of the academic year and in accordance with the students’ needs at those particular times. Howard University Day of Service (HUDOS), for instance, is held annually in August at the beginning of the Fall semester. “The intention is to expose incoming students to Howard’s tradition of service. This service-learning experience allows Howard University students to discover the power of ethical leadership and civic responsibility. HUDOS is held in collaboration with over 80 sites across the district and exposes students to the communities that surround Howard,” says Andreya Davis (B.A. ’14, M.A. ’23), assistant dean for faith-based and community initiatives. There are also service projects during Homecoming and around the holiday season. “We really have a well-oiled machine [that effectively introduces] students to Howard’s tradition of service.”

Howard’s motto, “Truth and Service,” is emblazoned throughout campus, constantly reminding students of these foundational principles upon which the University was built. While Davis appreciated those words when she first encountered them at Howard, “Alternative Spring Break is the program that helped give those words meaning,” she says. “[It] took them off a sheet of paper and really actualized what the motto means.”

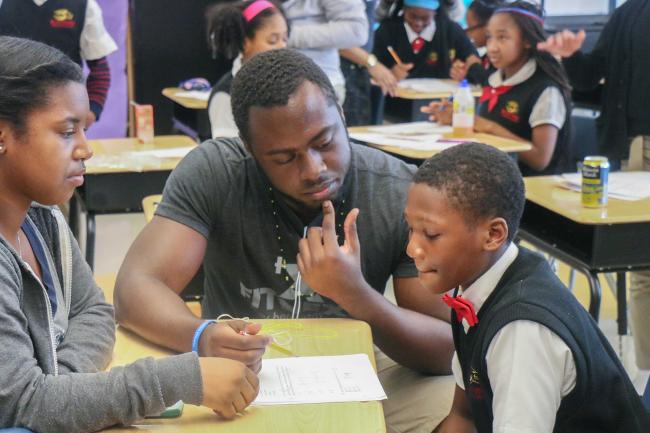

As a freshman, Davis was a team leader for an initiative in her hometown of Detroit, where they worked to improve literacy in the Black communities and help Black students with college preparedness, including admissions essays. From very early on in her Howard experience, she was exposed to what made HUASB such a special program. As an entirely student-run operation, the students have the opportunity to select the communities they will help, to decide on the service projects and organize the logistics on the ground. While the program itself takes place during Spring Break, it is truly a year-long project for those most intimately involved.

Bernard Richardson, Ph.D., dean of the Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel, often references a quote from Benjamin E. Mays, who helped lay the groundwork for the civil rights movement, in the context of student leadership: “Don’t seek greatness; seek to serve, and if you seek to serve, you will bump into greatness along the way.”

Part of what distinguishes HUASB from similar programs at other institutions of higher education has to do with the leadership development component. Alternative Spring Break is not just designed to empower students to do good and feel good. It is training them for a life of leadership and service.

Davis says she knows students that have been so affected by their HUASB experience that they emerge from the program completely transformed. “A lot of our students have changed their career pathways as a result of Alternative Spring Break. We’ve had students who chose to dedicate their life to teaching because [during HUASB] they were in the classrooms for a week and saw that there were more Black teachers, who were also dedicated, empathetic and engaged, needed in the communities we were serving,” she says. “One of our students decided to move to Ghana because he was able to travel there for the first time [during] Alternative Spring Break, and it changed his life and the lens through which he looked at the world.”

For students at Howard, there is an element of gratitude and responsibility to their service. Crewe calls it a “Sankofa moment,” a word that comes from the Akan people of Ghana meaning “to go back and get it.” The term is often associated with the symbol of a bird who is flying forward with its head turned to look behind it.

“We are always looking backward. [I’m] not just looking [forward] to what I can achieve, but [back to those] who paved the way for me to be here. Because there was a social injustice done to someone, I have an opportunity and a responsibility [to serve them],” Crewe says. “Service at Howard often has a social justice lens to it. [We] identify communities, not just in need, but communities who have had a history of oppression and marginalization. So, I think Howard service tends to bend toward the arc of injustice. … That’s in [our] DNA.”