It’s the second week of Black Music Month, and music professor Carroll V. Dashiell Jr. isn’t just reflecting on rhythm and melody — he’s reflecting on memory, history, and sound, and how enslaved people bent and twisted notes as a means of survival.

Dashiell, chair of Howard University’s Department of Music, is a seasoned jazz bassist and lifelong educator. His father walked the campus and played baseball at Howard University in the 1950s. The younger Dashiell followed. In the late ’70s and early ’80s, earning Howard degrees in music, music education and jazz studies.

He’s been back at Howard for the past two years as department chair, bringing with him more than three decades of experience from East Carolina University. In a recent conversation, he explored the deep roots of Black music and Howard’s historic role in nurturing it, reminding us that Black music isn’t just something we hear but something we inherit.

In your view, why does Black Music Month matter?

Dashiell:

I think Black Music Month is a great idea. I appreciate it because it really highlights the contributions of African Americans to the music industry — and that’s not just limited to one genre. We tend to think of Black music as hip-hop or Motown, and then before that, jazz as the predecessor.

Black music is a combination of all those things. What I’d personally like to see more of is tracing the history — the lineage and the connections of the different genres within Black music. And then you start asking what Black music really is, you realize it goes even deeper than that — of what is Black music.

What is Black music?

Dashiell: Black music is a music that is based on the heritage of the African American. It goes all the way back to the origins in Africa — the drum being one of the very first instruments, other than the voice — and it’s really about communication.

Black music is all about communication. I think you’ll find that the arts are about communication, but specifically, Black music is about communication. When you think about the drum, when you think about the music that wasn’t even considered a music form — the field holler — when we were dealing with the slaves. The slaves would actually have a person who would recite something. This was done through what I call the bending and twisting of notes.

You might have slave-field one and slave-field two connected to each other, but a mile apart or whatever. When they were planning the escape, they would use the bending and twisting of notes."

You might have slave-field one and slave-field two connected to each other, but a mile apart or whatever. When they were planning the escape, they would use the bending and twisting of notes. One would recite something, and the rest of the field would respond — we call that call and response. The thing that’s so cool about that, and going back to communication, is what was being said and sung were actually directions, as far as: "We’re leaving tonight. We are going north, and we are going to take 50 people with us." The master and the field boss were standing right there, and they didn’t know what was happening. We were communicating with each other.

You go further in the history of our music, and you think about the Blues. The Blues was all about communicating. And the spiritual — the spiritual was about communicating: "Go Down, Moses, way down in Egypt land." Those things that are very important.

When you bring it up to today and talk about hip-hop — hip-hop was all about communication. Talking about what was happening, or what is happening, in our neighborhoods, in our environment. A lot of times putting it in a form or format where you knew what we were talking about. Or, when you talk about Chuck Brown, for instance: MasterCard and Visa, American Express — I don’t have no credit card, but the cash is the best. To quote a lyric — that is something that is very communicable.

A lot of people hear “Black Music Month” and think Motown or hip-hop. You’ve said there’s so much more. What do we miss when we limit the definition?

Dashiell:

Lots of characteristics of our African American heritage have filtered into all parts of life and aspects of society. The same is absolutely true about African-American musical roots — from the grooves to the placement of the notes to the placement of the beats.

Dashiell, over the course of his career, has performed with a wide range of artists across genres, including Bobby Watson and Horizon on Blue Note Records, Stephanie Mills, and The Yellowjackets. He also launched his own record label and production company, further expanding his footprint in the music industry.

In addition to his work as a performer, Dashiell taught at the University of the District of Columbia and St. Mary’s College of Maryland. He later became the first Black professor in the School of Music at East Carolina University — a milestone that marked the beginning of a 34-year tenure in higher education.

And Howard? What role has Howard University played in cultivating those roots?

Dashiell:

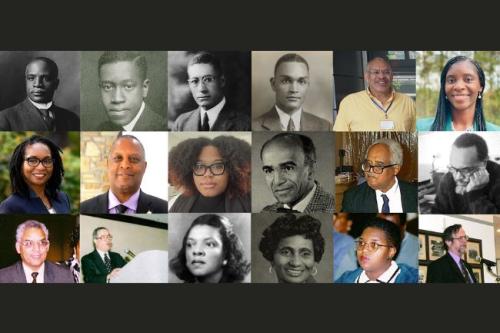

At Howard University, we have such a rich legacy of African American influences in music. You look at great artists that have come out of Howard University, the music department. You have Benny Golson, for instance, the jazz legend. Then you’ve got Jessye Norman. She was an incredible classical opera star, sought out all over the world. Jazz fusion, if you want to call it, or R&B groups that were tied directly into jazz.

You had Donald Byrd, a professor in the College of Fine Arts and the Department of Music, and he had the group The Blackbyrds. You have that lineage and legacy that goes on. With The Blackbyrds, you have tunes like “Rock Creek Park,” “Walking in Rhythm,” things like that.

Then you have, more recently, Roberta Flack — how many people don’t know "Killing Me Softly with His Song?" You have Donny Hathaway, who actually got put out of the music department on the third floor at one point because he was doing more contemporary sounds in developing his music. Because at that time, the music department only allowed classical music.

Then you take it a step further into gospel. You’ve got Richard Smallwood — what church could you go into in the world now that doesn’t do “Total Praise”? You have all of those things. We also had, for instance, Michael Bearden, who was musical director and producer for Michael Jackson. All came directly out of the music department at Howard. That’s that lineage, and we don’t talk about it often enough. We talk about the other things in the college, which are great. But those are some very significant people and events from the music department at Howard.

You mentioned being on the road with Ray Charles at just 18. How did that experience shape you?

Dashiell:

Ray taught me that music is honesty. No matter how complex the arrangement, it had to feel true. I was young, still figuring things out. But watching him perform, you could feel the whole room breathe with him. That shaped me more than any class could. He made every note count.

What would you say to young artists or students today who want to tap into this legacy?

Dashiell:

We are continually on this journey to find what is next. That is what is so important and is a focal point that the music department at Howard is offering to all of our students. “What is next?” I always ask all of my students, when they win their first grammy, when they get up there and say thank you for this whoever they are thanking. I will be the first person jumping up and down, screaming and hollering and applauding for you. As soon as you finish that last word, I’m going to ask you “What’s next? What you got next? What you got for me now?” That’s the thing — that exploration and pushing the envelope forward.

A prime example is my daughter, my baby girl (Christie Dashiell). She’s a first-time Grammy nominee this year. I had the pleasure of accompanying her out to the Grammys. She’s also a professor in the Department of Music, teaching jazz vocals. That’s a true indication of the lineage, the legacy, and also pushing it forward.

What’s next for the Department of Music at Howard?

Dashiell:

We’re leaning into that legacy. We want to strengthen our pipeline, grow our partnerships, and push more of our students into both performance and scholarship. There are too many stories yet to be told—by us, about us, for the world to hear.

###