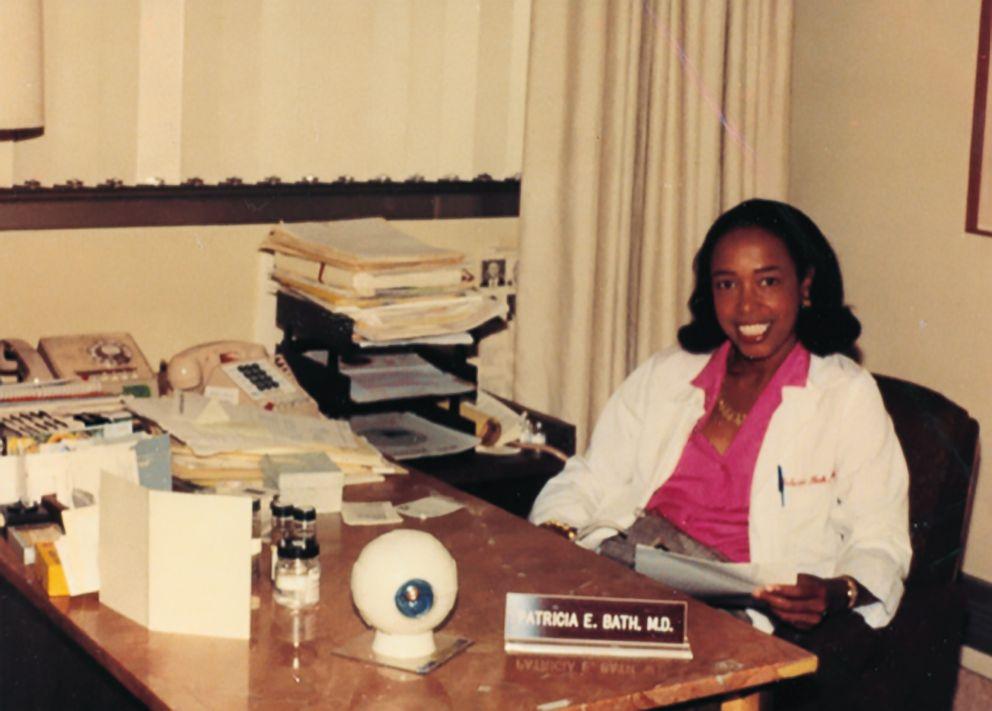

It’s not often that a single individual accomplishes as many “firsts” as Howard University alumna Patricia Bath (MD ‘68). In the decades following her graduation from the Howard University College of Medicine, Bath became the first Black woman to complete a residency in ophthalmology at New York University, the first woman to chair an ophthalmology residency program in the United States, and the first Black woman doctor to receive a medical patent in the U.S. for her invention of laser cataract surgery.

In the face of systemic racism and sexism, Bath excelled as a doctor, researcher and inventor, opening doors for generations to come. After completing her M.D. degree at Howard, Bath returned to New York, where she was born and raised, to intern at Harlem Hospital and complete a fellowship in ophthalmology at Columbia University.

Bath created a new discipline called community ophthalmology, in which volunteers are trained as eye care workers to provide primary eye care to chronically underserved populations.

Bath noticed clear racial and economic disparities between the eye clinic at Harlem, where half the patients were blind or visually impaired, and the eye clinic at Columbia, where very few patients were dealing with blindness or visual impairment. She conducted a retrospective epidemiological study and determined that blindness among the Black patient population was double that of the white patients. In response to her findings, Bath created a new discipline called community ophthalmology, in which volunteers are trained as eye care workers to provide primary eye care to chronically underserved populations. Community ophthalmology is now practiced around the world.

In 1981, Bath envisioned a technology that would revolutionize cataract surgery: a laser probe that vaporizes cataracts. UCLA lacked the laser technology needed to bring her idea to fruition, and she found that she had hit a “glass ceiling” in the U.S., so Bath moved her work to Germany to test her design using the most advanced laser technology in the world at the time. In 1988, she received a patent for the device, which she called the Laserphaco probe.