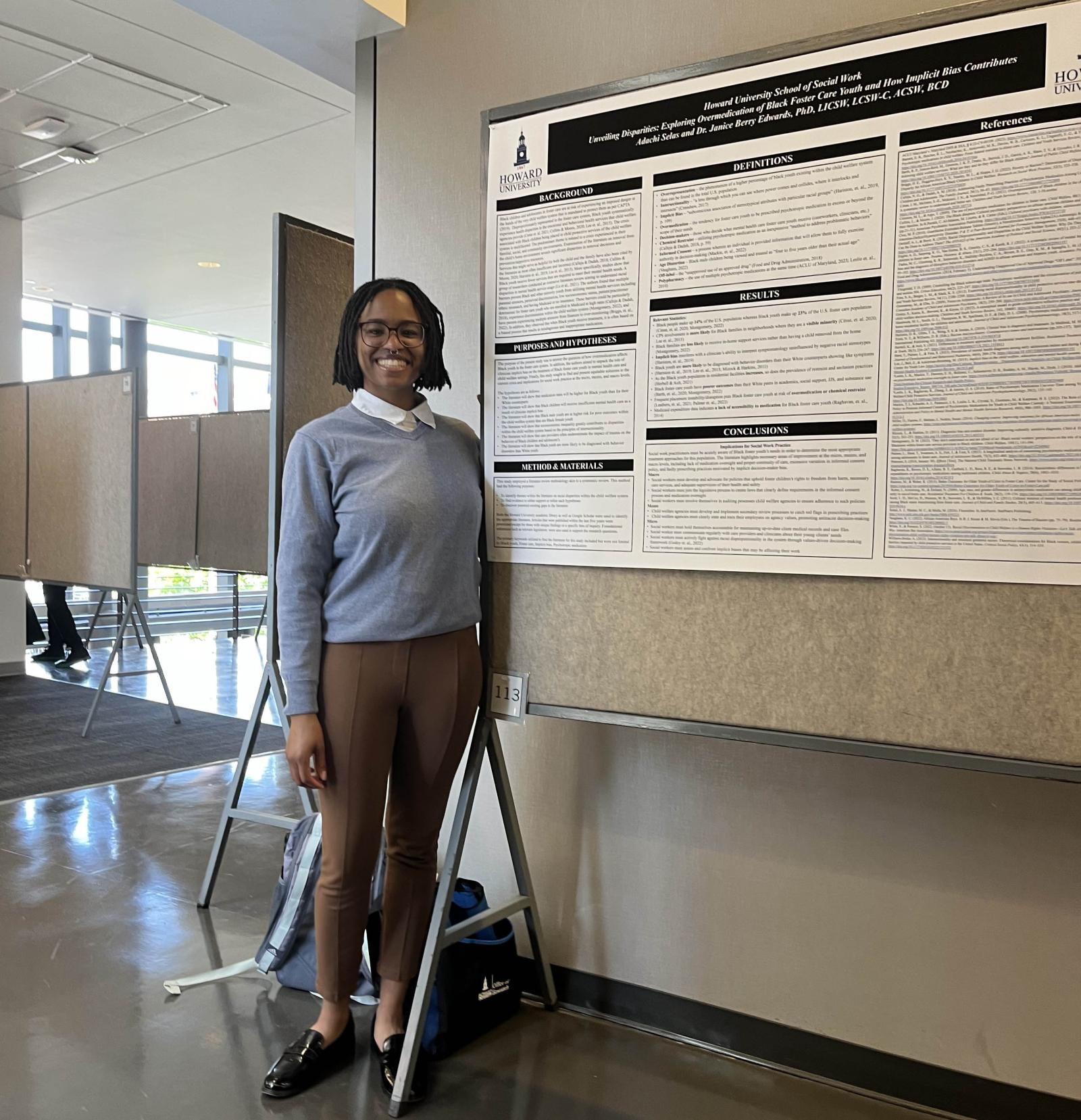

As Howard University celebrates Research Month and prepares to send off another graduating class, the School of Social Work proudly highlights the transformative work of graduate student Adachi Selas, whose research and advocacy center the urgent needs of one of America’s most vulnerable populations: Black foster care youth.

Selas’s journey to Howard was, in many ways, destiny fulfilled. “I had always really wanted to come to Howard,” she shared. “Even though I was homeschooled, my parents instilled a strong pro-Black education in us. So, attending an HBCU was always important to me.”

While she didn’t land at Howard for her undergraduate studies, she found the perfect match for her graduate journey in the university’s renowned School of Social Work. Drawn by its emphasis on culturally grounded practice and community care, Selas knew she was in the right place.

What she didn’t expect, however, was to develop a deep passion for the very area of social work she had once shied away from — child welfare. “I initially thought I wouldn’t go into child welfare work,” she admitted. “There’s high burnout, and I wasn’t sure I was up for the challenge.”

But her first-year internship at Washington, D.C.’s Child and Family Services Agency quickly shifted her perspective. There, Selas encountered the real stories behind the statistics, working directly with teens, parents, and social workers who illuminated both the heart and complexity of the system.

One case in particular, involving a 13-year-old boy prescribed medications not approved for his age or diagnosis, became the spark for a larger inquiry. “That case was very concerning to me,” she said. “And when I started asking more questions, I learned this wasn’t an isolated situation.”

This experience would evolve into her 2024 research paper, “Unveiling Disparities: Exploring Overmedication of Black Foster Care Youth and How Implicit Bias Contributes,” co-authored with Janice Berry Edwards, Ph.D. (MSW ’78), chair of direct practice at the School of Social Work. The paper explores how Black youth in foster care — already overrepresented in the system — are more likely to be prescribed strong medications such as antipsychotics without thorough evaluation or appropriate diagnosis.

“Black youth are often given behavioral disorder diagnoses rather than mood disorders,” Selas explained. “These behavioral diagnoses are more likely to lead to stronger medications and also increase the chances of juvenile justice involvement.”

What’s driving this disparity? Selas points to implicit bias, both systemic and individual. “Providers may view Black children’s behaviors as more dangerous or more in need of control,” she said. “That leads to stronger medications being prescribed rather than engaging with the underlying issues, often trauma or depression.”

Her work doesn’t stop at identifying problems; it offers actionable solutions. One of the more troubling findings in Selas’s research was the lack of informed consent and limited collaboration between social workers, parents, and prescribers. “Many social workers aren’t required to learn psychopharmacology, so they don’t always know enough to advocate effectively,” she noted. “And when parents aren’t being fully informed, children fall through the cracks.”

To counter this, Selas advocates for mandatory psychopharmacology training for social workers and better interdisciplinary communication across care teams. She also calls for policy-level changes, including stricter informed consent laws and requirements for full medical evaluations before prescribing psychiatric medications to foster youth.

It means asking questions, inviting families into decision-making, and recognizing that what might be pathologized in one culture could be entirely normal in another.”

Central to Selas’s philosophy is the concept of culturally intelligent interventions – a recurring theme throughout her research. “Culturally intelligent practice means not taking a universalist approach,” she said. “It means asking questions, inviting families into decision-making, and recognizing that what might be pathologized in one culture could be entirely normal in another.”

These interventions also lean into community-based care, which Selas sees as essential to countering the systemic removal of Black children from their homes. “Instead of extracting children to provide services, we should be bringing services into the community and helping families stay together whenever possible,” she said.

Selas’s perspective is deeply intersectional. “Gender and race both matter. Black mothers are more likely to be surveilled and have their children removed. Black boys are more likely to receive behavioral diagnoses and be pushed into the carceral system,” she said. “We can’t just look at one aspect of identity.”

Looking forward, Selas’s commitment to health equity and culturally grounded care continues post-graduation, when she will join only the second cohort of behavioral health fellows with Unity Health Care. Though the position is not directly connected to foster care, Selas sees a clear throughline.

“I’ll be working with majority Black and Latino patients, and I want to bring my culturally intelligent lens to that work,” she said. “Mental health looks different in different communities, and I want to help people feel seen and heard in ways they may not have before.”

Her biggest takeaway from her time at Howard? Research isn’t just about data, it’s about impact. “My hope is that this research doesn't just sit on a shelf,” Selas said. “I want it to inform real changes in practice, education, and policy — changes that protect and uplift Black children, their families, and their futures.”

As she completes her Long Walk this May, Selas represents not only the power of personal transformation but also the promise of a profession made better by culturally aware, rigorously trained, and justice-minded leaders. Her work is a reminder that Howard University’s legacy of excellence isn’t just academic. It’s also deeply human.