On December 13, 1928, the United States Congress amended Section 8 of Howard University’s Act of Incorporation to include the authorization of the institution's annual appropriations. Initially established under Howard’s first Black president, Mordecai Wyatt Johnson, these appropriations have continued to aid in the construction, development, improvement, and maintenance of the University for nearly 95 years.

At the start of his 34-year tenure, President Johnson prioritized a resolution concerning the financial standing of the University. At the time, the University would receive subsidies for annual appeals to Congress, ranging from $10,000 in 1879 to $200,000 in 1926. According to the Journal for Blacks in Higher Education, "These grants were never adequate to enable the school to operate at a level commensurate with the standards of a full-fledged university. In the absence of statutory authority for the appropriations, the fiscal health of the university would remain tenuous unless the situation changed."

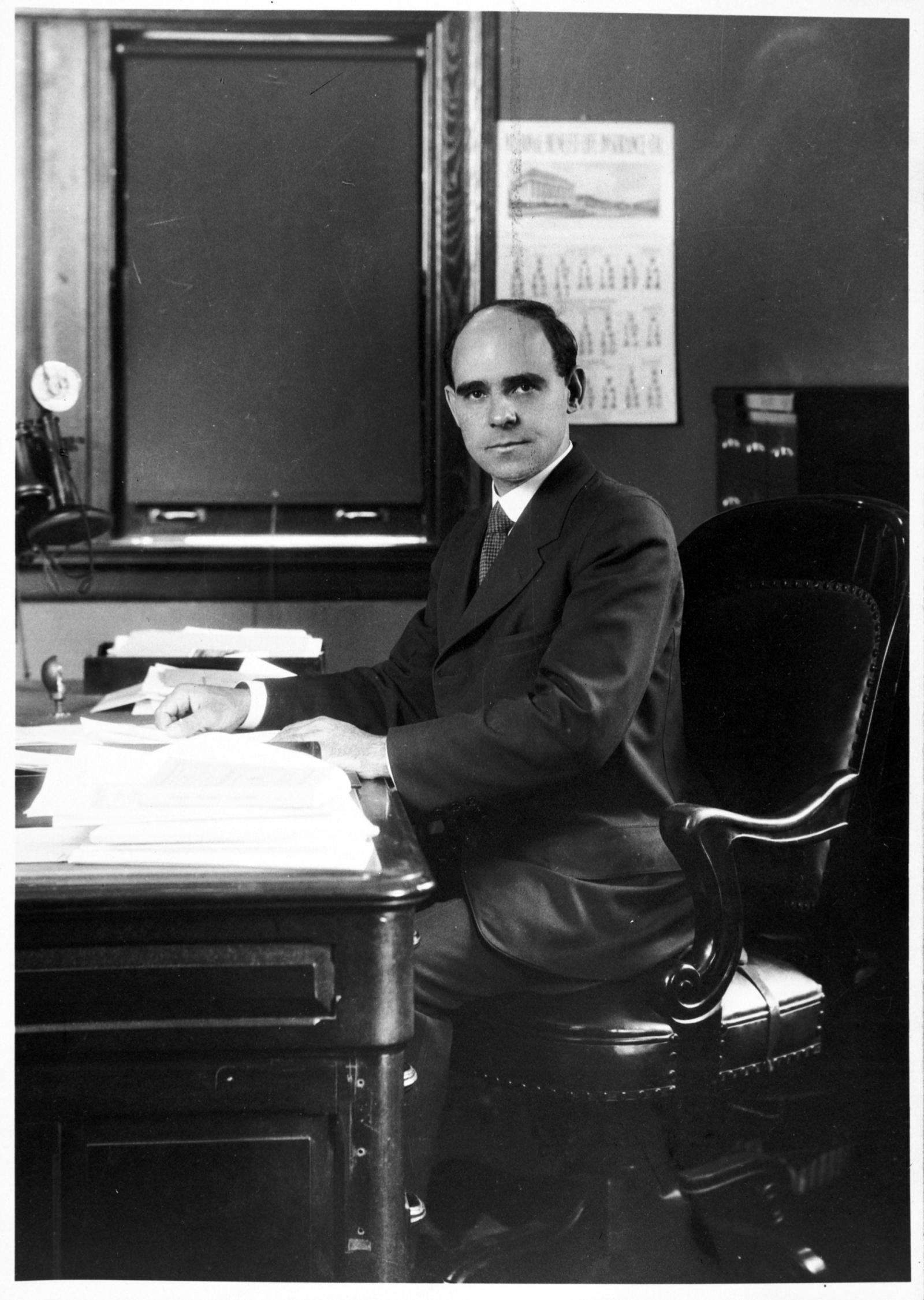

Thus, Johnson began his push for an amendment authorizing an initiative that would propel the University forward. His efforts were strongly backed by Louis C. Cramton and Daniel Alden Reed, who initially introduced the bill. While many proponents of the amendment existed, its propositions still were met with staunch opposition from all angles.

One of the most vocal skeptics was Representative B. G. Lowrey from Blue Mountain, Mississippi, who, according to "Howard University: the First Hundred Years, 1867-1967," asserted that "… the Negro race through the South where I live is more abundantly provided for as to college education and college opportunities according to their needs than the white race." This was not the only widely spewed falsehood of its nature. Other representatives continued to challenge the amendment under the pretense that it would give Black institutions an unfair advantage on the playing field of higher education, going as far as to say that white people in the south "are the negros best friends."

Reed worked to provide statistics that historically proved this had not been the case. Not only was there a disproportionate ratio of Black students in schools nationally based on population, but historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) were severely underfunded compared to their white counterparts. Cramton supplemented these arguments with his own statistics, stating, "It is this discrimination that creates this national need for a great colored university."

In response to the frequent and fervent retortions, Cramton also declared Howard University "a national school to meet a national need." In emphasizing the excerpt from the amendment that states, "The University shall at all times be open to inspection by the Bureau of Education and shall be inspected by the said bureau at least once each year. An annual report making a full exhibit of the affairs of the University shall be presented to Congress each year in the report of the Bureau of Education," Cramton proved the University would only receive appropriations if Congress deemed it necessary, and saw appropriate allocation of the funds each year.

The House approved the bill on March 29, 1926, "by a tally vote of 226 yeas, ninety-four nays, two 'present' and 112 not voting."

Now, nearly 95 years later, the appropriation amendment provides a framework that allows Howard to adhere to the goal of HBCUs around the country: To foster excellence in the Black community, and promote equity in higher education.

"Historically Black Colleges and Universities, like Howard, provide students of diverse backgrounds with a world-class higher education and foster an academic learning experience that helps students grow into our leaders of tomorrow," said U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin. Sen. Baldwin also serves as the chair of the Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health, and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies, which manages the appropriation amendment today.

"Supporting our HBCUs and their mission is essential to increasing equity in our communities, but especially in higher education and the workplace," Sen. Baldwin continued. "By providing HBCUs with robust funding to support their academic programs, research, support services and infrastructure, we can give more students the opportunity to succeed during college and beyond.”