At Howard, it is often said that we stand on the shoulders of giants. But sometimes, these titanic figures can be too big to fully take in, their aggrandized bodies so mammoth that our eyes convince our brains that we are standing on hills or mountains rather than on the shoulders of one who worked so hard to rise up in order to grant us these new heights.

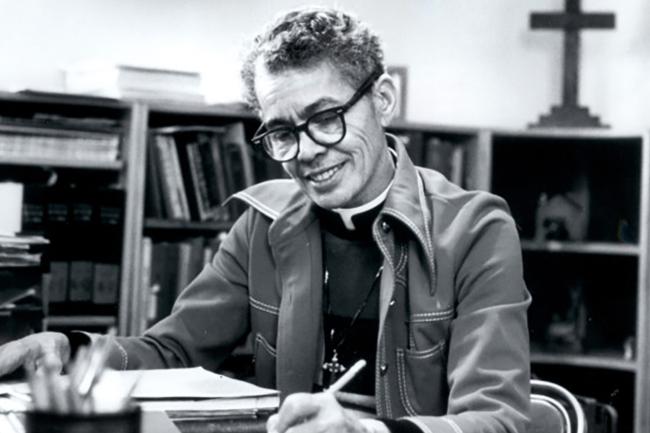

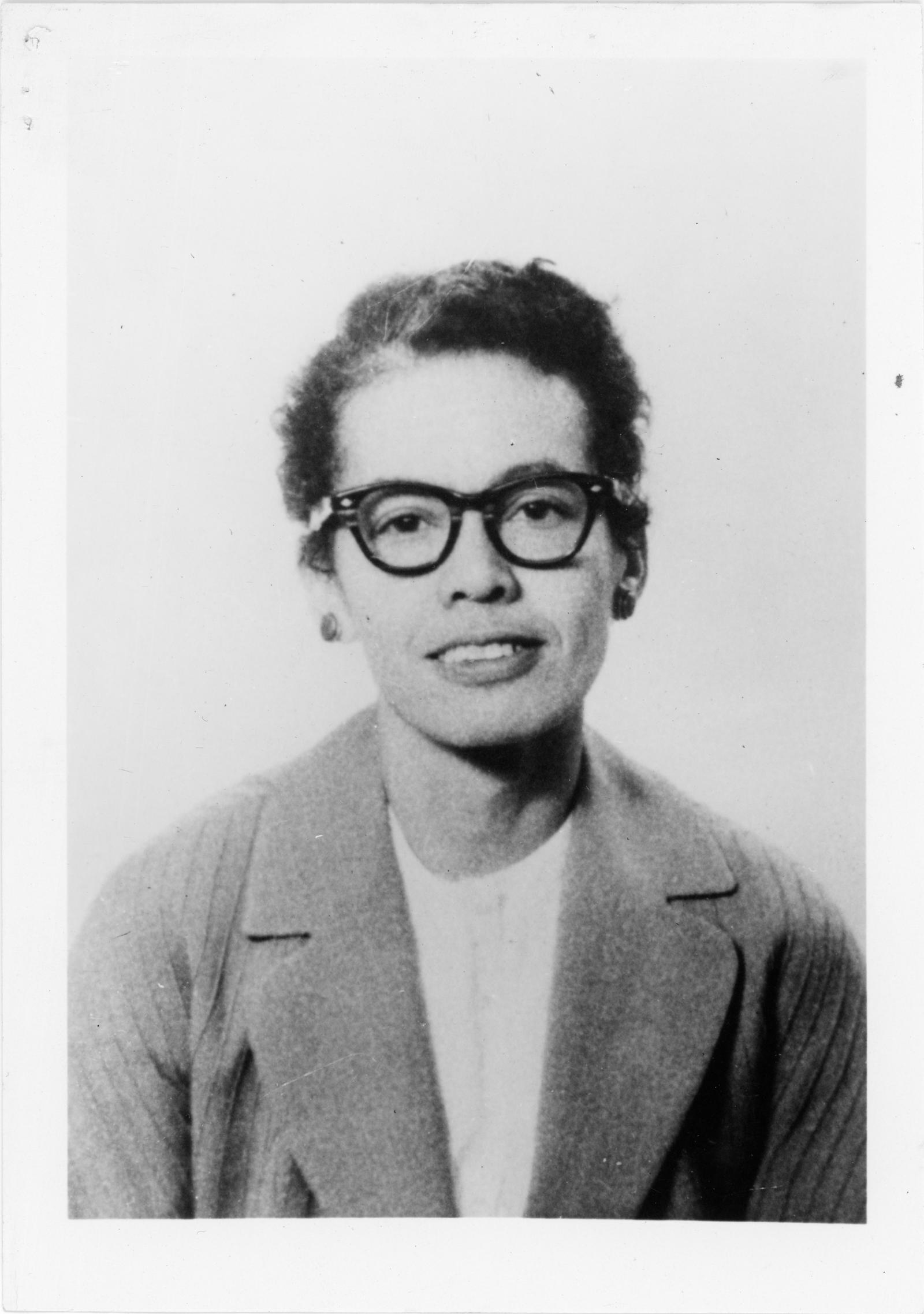

So was the case with Pauli Murray (J.D. ’44, H. ’17), a figure of monumental importance who, at least in the public consciousness, for so long languished in relative obscurity. However, in recent years, Murray has been receiving a long overdue revival and much-deserved recognition, culminating with the just-released Amazon Studios documentary “My Name is Pauli Murray.”

In many ways, Murray was a person ahead of their time. Murray was a civil rights lawyer, whose legal thinking influenced Ruth Bader Ginsburg to argue against discrimination on the basis of sex and the prevailing legal team behind Brown vs. Board of Education to argue that separate was inherently unequal. Murray was a writer and a poet, who used their pen to speak truth to power and lament the injustices perpetrated against Black Americans and women. Murray was an Episcopal priest, widely regarded as the first woman to ever be ordained in the order. But Murray was also someone who struggled with gender identity; during their lifetime, Murray sought, and was denied from receiving, gender-affirming medical care. While Murray did not use these terms, today Murray is widely considered to be gender nonbinary or gender fluid.

Murray was certainly cognizant of the public legacy they would leave behind; Murray wrote an autobiography and determined that their personal files and archives should be housed in Schlesinger Library at Harvard University. But Murray did not speak or write publicly about their gender identity or sexual orientation, despite chronicling these matters privately in great detail.

Born Anna Pauline Murray, Murray chose to go by “Pauli,” a name that was more gender-neutral and in-keeping with what Murray described as their “he/she personality.” But while Murray had to struggle privately with their gender identity, they also had to suffer publicly from the dual discrimination of being seen as both Black and female, coining the term “Jane Crow” to capture the plight of Black women.

Even on Howard’s campus, where Murray graduated from the School of Law in 1944, Murray has long been known, but perhaps not in full, and perhaps not to the same extent as some other esteemed alumni. Where Kamala Harris attributed her desire to come to Howard in order to model herself after Thurgood Marshall, someone like Pauli Murray might have had a more subtle pull. Howard students, faculty and staff were likely attracted to the University because of Murray’s ideas, even if they never knew Murray’s name.

Lisa Crooms (B.A. ’84) has found herself following in Pauli Murray’s footsteps throughout her educational and professional career, first as a Howard undergraduate student and then as a law professor at Howard – though it took some time to discover who was leaving those giant-sized imprints in the ground upon which she tread.

Crooms was interested in the legal theories supporting feminism and human rights, when one day, a few years after she started teaching at Howard’s School of Law in the mid-1990s, J. Clay Smith Jr., former dean of the School of Law and well-regarded legal historian, recommended that she look into Pauli Murray. At that time, Crooms had never heard of Murray. But shortly thereafter, Murray started showing up wherever Crooms looked.

“[Murray is] everywhere,” Crooms says. “The way [Murray] put things together [from a legal perspective] made a lot of sense. It was a precursor to what is now talked about as intersectionality and critical race theory.”

For someone whose ideas were unavoidable, it was remarkable how invisible she could be.

Crooms theorizes that part of Murray’s burgeoning recognition today has to do with Ginsburg’s own meteoric rise in popular culture. Prior to her death last year, Ginsburg regularly cited Murray as one of her primary and most important influences. Greater popular recognition of Ginsburg has led to similar results for Murray.

But in addition, Crooms believes there are aspects of who Pauli Murray is as an individual that resonate strongly with our culture today.

“In some ways, Murray is an every person,” says Crooms. No matter one’s race, gender identity or sexual orientation, “there’s something [about Pauli Murray] that looks familiar” and is relatable.

Crooms now teaches a class about Pauli Murray, where she explores the idea of equality. So, what does equality mean according to Murray?

“Ultimate freedom for everyone [means that] all aspects of everybody’s humanity [is] recognized and not denigrated,” Crooms says. People shouldn’t have to be “stuffed into a box” to receive equality under the law.

Certainly, Murray did not live in a world where Murray’s full self was recognized, validated and appreciated, where Murray felt free to match their public persona to their private one. And while Crooms believes Murray would consider our society to still be falling short of this standard, perhaps Murray’s newfound recognition is acknowledgement of the progress we have made and the direction we are heading.