As Howard University celebrates 75 years of desegregation in the military, the University’s own contribution to supporting the U.S. armed forces dates back more than 100 years.

Through the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), students receive a college education paid for by the U.S. Military. The students, called cadets, serve in the military after graduation.

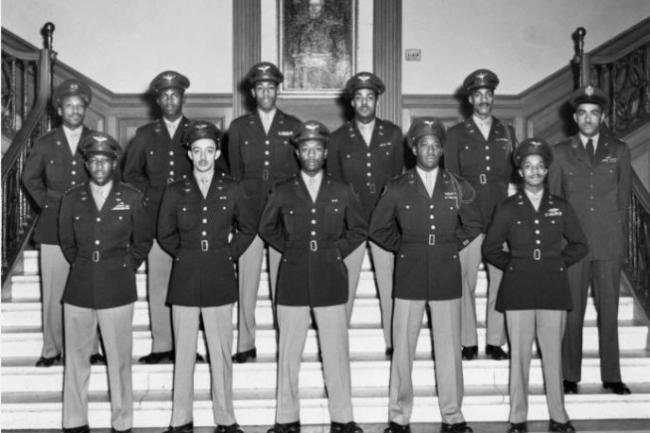

Howard began organized military training of Black officers in 1917 and created an official ROTC detachment in 1918. The goal was to ensure Black military members were more than just infantrymen. Howard Army ROTC has commissioned more than 1,000 officers since its inception, many of whom went on to become generals. Howard is one of the largest producers of Black candidates for the Army and the Air Force.

“The idea to bring military education to Howard started with at the urging of Howard trustee Joel Spingarn. He spoke with students at a rally in Rankin Chapel and he said that they should really lead the effort to get African Americans involved in World War I and they took that charge and formed the Committee of Concerned College Men,” said Lopez Matthews, PhD, author of “Howard University in the World Wars” in an episode of “@Howard” produced by WHUT.

In 1947, the Air Force was split from the Army as its own branch, and Howard also created a separate Air Force ROTC program. The Howard Air Force program ensured it produced qualified soldiers. In 1948, the program won the award for Air Supply – only a year into the new program, beating out traditional military schools like the Citadel. In the same year, President Truman issued the executive orders to desegregate the federal government workforce and the military.

“Being in the ROTC at Howard is a pretty unique experience because it represents the future of our military, but not necessarily what it looks like today.”

Initially, ROTC was mandatory for all male students at Howard who were deemed physically fit. In 1967-1968, students began protesting the mandatory status of ROTC with sit-ins. Secretary Lewis Blaine Hershey, head of the selective service board, was keynote speaker for graduation in 1968 where graduates protested the compulsory ROTC program and burned an effigy of him from the tree in front of Douglass Hall. “They said…. we don’t want to be forced to fight for a nation that does not support Black people,” Matthews said. The students’ protests succeeded, and the requirement was removed.

In the 1950’s and ’60s, the ROTC program wanted to include women, and Miss Coed Cadet became a representative voted in by the Howard student body. She donned a uniform and took photos, but it wasn’t until 1970 that women were allowed into the ROTC program.

In the late 1980’s, the ROTC program became a consortium program where all ROTC students in the District of Columbia receive their training at Howard even if they were students of other universities.

Fifty years since the ROTC’s gender inclusion, Kendall Franklin, a rising senior psychology student from Atlanta is part of a panel discussion celebrating the 75th anniversary of desegregation. She was awarded the HBCU high school scholarship which provided her with a full ride scholarship to Howard University within the ROTC program.

Ahead of her final year the Howard, Franklin is part of the University ROTC Air Force class and is the number one cadet in Howard’s Air Force 400 Class.