Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), an aggressive cancer that originates in the bone marrow and affects the blood and immune system, has proven a more deadly illness in African American patients – and particularly younger individuals – than compared to their white counterparts. Research indicates that among Black AML patients, 11% died within 30 days of beginning treatment, compared with 2% of white patients. Five-year survival was 32% for Black patients compared with 46% for white patients.

Further studies have revealed that younger Black patients with AML have not benefited as much as white patients from recent progress in AML treatment in the United States. Among Black patients between the ages of 18 and 29, the rate of early death was 16%, compared with only 3% for white patients in the same age group.

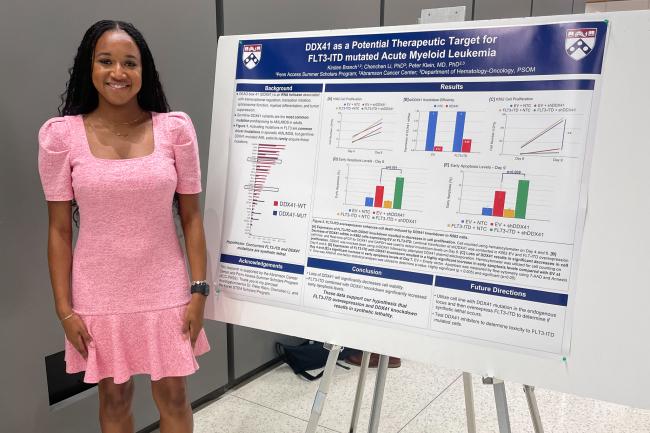

Addressing these disparities has required a multifaceted approach. In this context, emergent scientists and researchers like Kirsten Branch play a vital role. A previous recipient of scholarship funds raised during Charter Day, Branch, a graduating senior biology major with minors in chemistry and psychology, has conducted AML research for the past two summers.

A member of the fifth cohort of the University’s prestigious Karsh STEM Scholars program, she found a passion for science as a high schooler inspired by the story of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose cancer cells originated the first immortalized cell line.

“Around the same time of COVID happening, I learned so much about disparities in medicine and wanted to be the kind of person to fix that,” Branch said, adding that these reflections led her to discover more about historically Black colleges and universities and Howard, more specifically.

“Being able to tie in almost every aspect of what I love – biology, caring about people, policy – I knew that I could do that through my career path,” she said. “That’s why I decided on biology for a major at Howard.”

Even just being in that space where we are underrepresented is very important.”

Despite its mortality rate among Black patients, AML research in that area continues to lag. Branch acknowledges she first wanted to study neurology, a topic she found more pertinent to her community, and was unsure whether her pivot to AML was warranted.

A conversation with a mentor helped shift her perspective. “I was telling them that I didn’t know about the research I was doing because I didn’t know if it would positively impact Black people directly,” Branch said. “They told me, ‘No, I have a family member who has AML, and I know it’s not talked about a lot in the Black community because there are other diseases that we experience, but AML is still something that affects a lot of people who look like us.’”

That exchange continues to shape Branch's approach and provided her a greater appreciation for representation across medical research. “Even things like AML, if you don’t have someone who is African American or Black behind-the-scenes doing the clinical trials, people are going to be less likely to want to participate in them,” she said. “Even just being in that space where we are underrepresented is very important.”

Post-graduation, Branch intends to continue her research this summer at the University of Pennsylvania before pursuing a dual MD/PhD, with the goals of becoming a medical doctor and healthcare policy advocate. Despite uncertainties around future research funding, she remains optimistic about the future of her field, bolstered by much of what she has learned as a Howard student.

“For a lot of people in the research world, it’s a very scary time, but I have a lot of solace in knowing this isn’t the first time we’ve been through scary times,” she said. “I’m just trying to navigate them and put my best foot forward, because I know I have the résumé and the skills to be successful in this space.”