The term “environment” is most often used to describe the natural world – the air we breathe, the water we drink. But architects like Bradford Grant, M.Arch, professor in the Howard University Department of Architecture, believe that the pursuit of environmental justice must encompass the “built environment” as well, meaning the homes and buildings where we live, work and play.

“The environmental impacts of climate change impact communities of color and low-income communities at much greater rates,” Grant says. “[Architecture] has become a really major factor in [environmental justice].”

A building’s construction and architecture represent about 40 percent of greenhouse gases that are emitted.”

“Architecture consists of everything,” says Nea Maloo, AIA, lecturer in the College of Engineering and Architecture. “Our buildings should be safe. I think it’s an architect’s job to save the planet.”

When we think of the primary contributors to global warming and climate change, we often think of machinery unearthing fossil fuels and factories coughing out black smoke. But those images overlook the impact of non-manufacturing facilities that populate our cities and suburbs.

“A building’s construction and architecture represent about 40 percent of greenhouse gases that are emitted,” Grant says. By designing more energy efficient buildings, it’s possible to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate the effects of climate change that disproportionately harm communities of color.

There are other ways architecture and the way we build our cities impact under-resourced and disadvantaged communities.

According to Grant, there are important questions architects must ask about the materials they use in their buildings. “Where [do the materials] come from? Where are those materials made? How are they made? And who is making them?”

The same way that people will talk about fair labor practice with regards to who’s picking their coffee beans, Grant says, architects talk about fair labor practice regarding the manufacturing of their building materials.

In St. Gabriel, Louisiana, near baton rouge, there is an area known as Cancer Alley, where chemical plants in predominately Black communities are used in the manufacturing of building construction materials. The materials may be toxic and more hazardous. So not only are they harming mostly Black people who live near and work in the manufacturing plants, but they are disproportionately harming people of color who live in communities that rely more heavily on the manufacturing of these toxic materials.

In another similarity to the food and produce industry, Grant also stresses the importance of building using local materials. The energy required to ship materials over long distances further adds to the carbon footprint of a building. The shorter the distance the materials must travel, the fewer greenhouse emissions are required to construct the building.

Maloo recently collaborated with Stanford University’s engineering department to create a Summer course on building decarbonization or limiting buildings’ carbon footprint. By combining her architecture expertise with her Stanford counterpart’s engineering knowledge, they were able to explore new ways to make buildings more energy efficient. While architects can create the designs for the buildings, it is the engineers who will create the products and systems that implement the architect’s vision.

“We complemented each other to teach this course,” Maloo says. “And I think that’s how environmental justice can happen. We need to work together to help save the climate.”

I believe in making our students the leaders of the future.”

Maloo was recently announced as the winner of the 2022 Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Course Development Prize issued in collaboration with the Columbia University’s Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture. Her winning course proposal, Environmental Justice (EJ) + Health + Decarbonization, will be offered beginning in Spring 2023.

Grant previously won the same award for his course Public Issues, Climate Justice and Architecture, which was offered for the first time in Spring 2021.

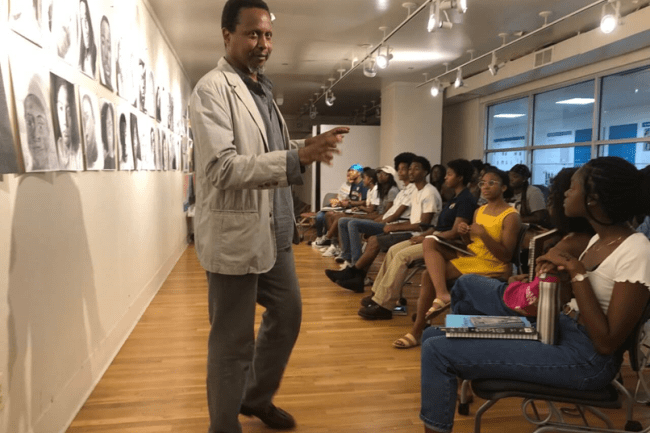

“As an architect, our primary job is to put buildings together. But also to go beyond that,” Grant says. “The general focus of the course is trying to teach some of these environmental justice principles and policies with an experiential take.”

Prior to the onset of the pandemic and virtual learning, Grant would regularly take his students out of the classroom. They would visit architectural locations, like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater. But just as often, they would go to public hearings “to advocate for a more inclusive and equitable building process.”

In addition to working at Howard, Maloo and Grant are also members of the Healthy Building Network, a group that advocates for nontoxic building materials as well as other healthy product options that go into buildings, like carpeting and insulation. Grant was also appointed to serve on a D.C. advisory neighborhood commission zoning, preservation and development board, a local governing body that reviews many of the new project proposals in its district. In this capacity, Grant works to negate the detrimental effects of gentrification as well as to advocate for the idea of equity and fairness, especially with regards to affordability, cultural preservation, and the displacement of low-income communities.

Architecture at Howard often emphasizes more than just technical skills; the focus is on training and developing ethical architects who design buildings through an environmental justice lens.

As important as she believes her work is as an architect, Maloo believes her greatest impact will come from teaching. “There are not many people of color leading sustainability out there in industry,” Maloo says. “I can only do so much [as an architect.] But if I can train [hundreds of students], how [much bigger] is the change? The reason I keep coming back to [teaching and curriculum change is because] I believe in making our students the leaders of the future.”