For example, Amazon’s bestselling medical training book ‘Netter's Atlas of Human Anatomy,’ includes about 180 figures where the sketches of each person indicate their skin color.

Out of nearly 180 figures that indicate skin color, only one shows a 'darker' woman and another shows a 'darker' man.

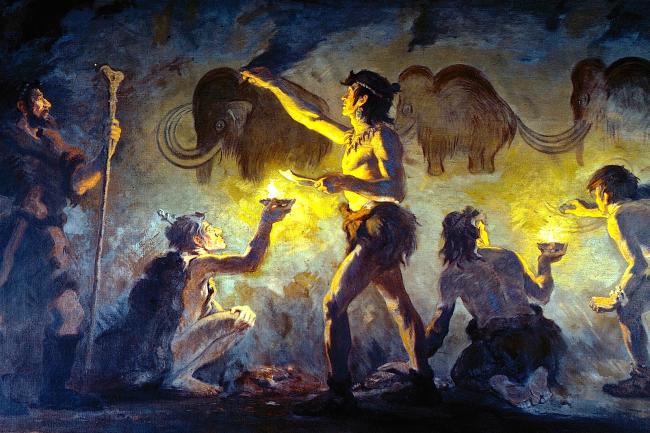

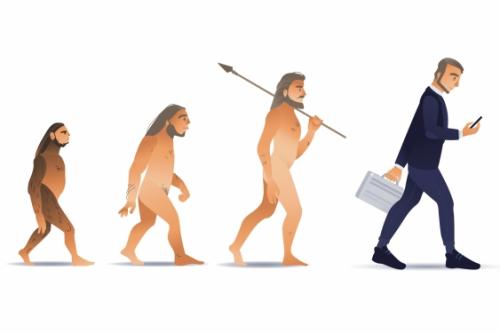

“There were darker people at the beginning stages of mankind like they were more ‘animal like’ and then they became whiter and whiter,” Diogo explains of the illustrations. “Some were dressed with a tie (representing) being civilized...the progressive whitening of the skin is inaccurate because most people living today are not 'white.’”

Jackson, the co-author of the project, called the study’s results of ample evidence of racism in society “evolutionarily inaccurate representations” that distort the view of diversity within the human race.

“The fact that it persists, generation after generation, suggests that the "bad ideas" of racism and sexism are serving some other purpose in the society,” Jackson says. “Retentions of white and male supremacy in evolutionary biology effectively exclude the participation of non-white, non-males in these areas. The deeply embedded bias in depictions of normalcy thwarts the aspirations, investments, and engagements of those who have been routinely excluded.”

The three student researchers are enrolled in the College of Medicine. Kimberly Farmer is a third-year medical student at Howard. Farmer discussed the significance of the study’s results from the angle of psychiatry and how images can affect self-worth.

“Just as far as basic human needs, there’s a need for belonging, there’s a need for acceptance and there’s a need for safety,” Farmer explains. “When we see images, especially pertaining to evolution really discounting Black people, and you don’t really see yourself in those spaces or evolving because it’s a white man as the pinnacle of evolution, I think that puts you at a disadvantage when you don’t see yourself or your own history.”

Within the research, she reviewed children’s books from Amazon and watched YouTube videos educating children in biology and anatomy. In this practice, Farmer only saw the sexism and racism scattered throughout the books and digitized on the YouTube platforms.

Diogo believes that the research being conducted by an HBCU makes the difference when discussing racial biases within American society. The extensive research, Diogo said, only introduced the new methods of teaching accurate history and balancing media representation. He hopes the Howard study can lead the charge in making a change.

Lived experiences of discrimination are validated in the HBCU atmosphere, a direct call of Howard’s responsibility to uplifting the truth while being in service to communities affected by racism.

“Howard can even do more in terms of research and press releases,” Diogo suggests. “Let’s apply for grants or even use Howard’s money to do an atlas that reflects diversity. We can be even more active to solve the problems. I think Howard, with its extraordinary history and mission, is the right place to lead this change.”