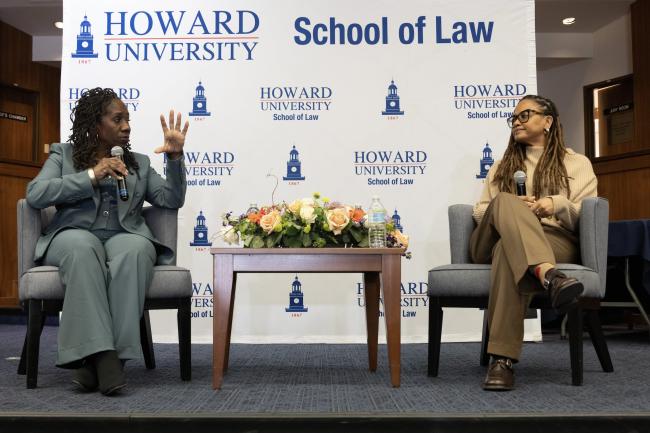

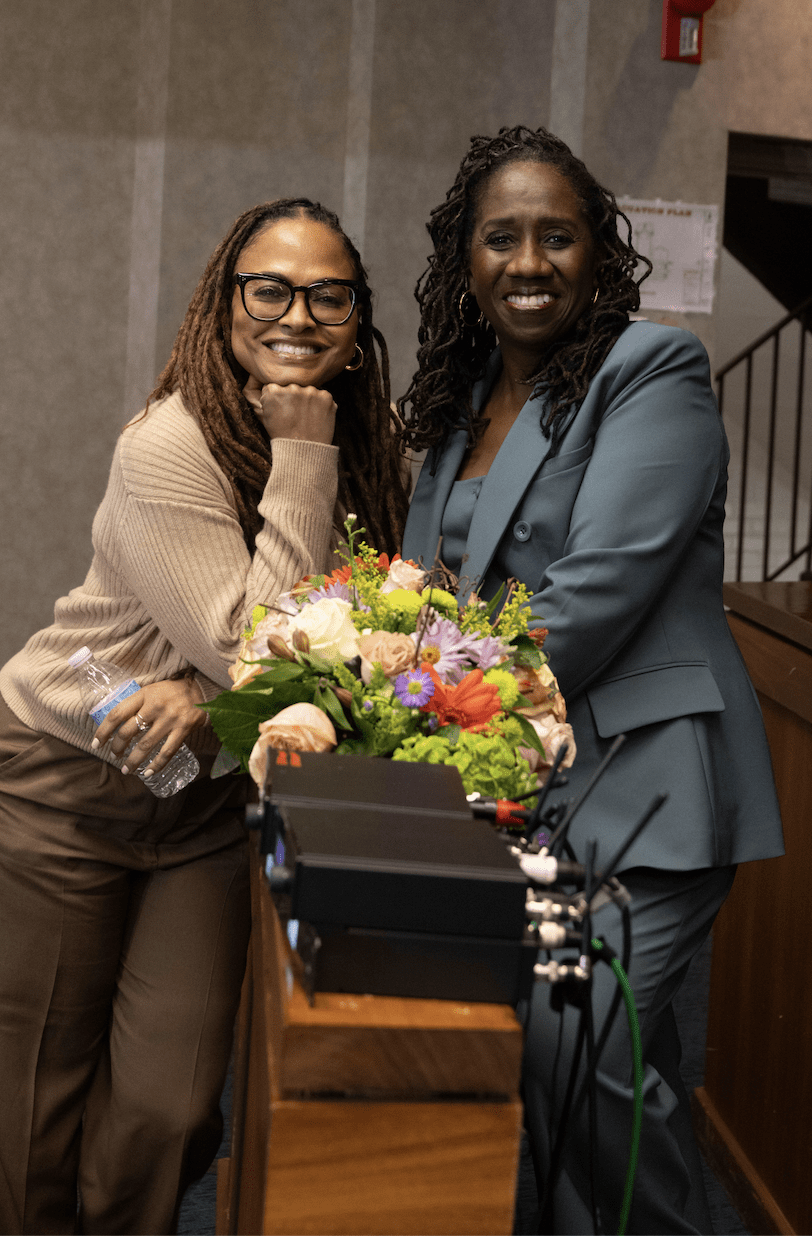

The synergy between law and narrative took center stage at the Howard University School of Law, where Ava DuVernay and Sherrilyn Ifill shared a heartfelt conversation marking the launch of the 14th Amendment Center for Law and Democracy.

Added to the Constitution after the Civil War, the 14th Amendment affirms that all persons born or naturalized in the United States are citizens, entitled to equal protection and due process under the law. The new 14th Amendment Center was born from a vision led by Ifill, who holds the Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., Chair in Civil Rights at Howard Law and is the former president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

The launch event, an extraordinary and jam-packed symposium held at Howard Law on March 28, featured prominent voices from law, history, religion, and community activism. Throughout the day, Ifill led panelists in an analysis of the 14th Amendment’s roots and role in the ongoing struggle to define citizenship, equal protection, and due process.

A standout moment of the symposium was a keynote conversation between Ifill and acclaimed director Ava DuVernay. Her Emmy-nominated series “When They See Us” tells the true story of five teenagers wrongfully convicted in the 1989 Central Park jogger case. The documentary has been praised for revealing systemic flaws in the legal system and showing how the legacy of slavery continues to shape racial inequality today.

DuVernay told the audience how the project was sparked by a message from Raymond Santana on Twitter, asking if she would consider telling their story. She agreed and arranged to meet him in New York — a visit that led to meetings with all but one of the other men.

“Then I flew to Atlanta to meet the last one, and I thought, I have to do this,” DuVernay said, adding that ultimately, “None of my films weave together as many threads of what we’re confronting in this country as ‘When They See Us.’”

Ifill said “When They See Us” powerfully captured the symposium’s core themes — democracy, citizenship, and equal protection — by showing the real-world consequences when constitutional promises are denied. She described the film as emotionally devastating, saying, “It broke my heart,” and noted that while she can usually watch most films more than once, she probably wouldn’t be able to bring herself to rewatch “When They See Us.”

She also shared how strongly her students connected with DuVernay’s work, especially the 2016 documentary “13TH,” which explores systemic racism and mass incarceration. Many had seen her films and were deeply moved by what they learned. Ifill described “13TH” and “Selma” as essential classroom tools, praising DuVernay’s ability to make complex constitutional themes both deeply emotional and accessible to audiences.

“You were in my class a couple months ago, and you could hear that a lot of my students have seen “13TH”... and any of your films could be shown in a 14th Amendment film festival,” Ifill said. “They’re all just dealing with these subjects — who we are, the constructs that hold us, the stories that are told about us.”

DuVernay acknowledged the emotional and political weight of her work.

“When a professor tells me, ‘I show When They See Us in my class,’ that makes me feel like I’m on the right track… That law and art should be more married together.”

DuVernay shared that she spent a year traveling and was surprised by the film’s global resonance. “In South America — Brazil, Colombia — you go there and “When They See Us” is huge. In India, too. For some reason, it really hit. People connect it to their own experiences with injustice, abuse of power, the courts.”

The symposium, titled “Reimagining American Democracy: The Fourteenth Amendment,” featured a series of thought-provoking panels that explored the amendment’s historical roots and modern-day relevance. Discussions ranged from the role of grassroots activism in shaping a more inclusive nation to the urgent need to revive the amendment’s equal protection clause. Other sessions examined how judges engage with 14th Amendment history, how artists help us envision democracy, and the responsibilities of civic institutions in upholding democratic values.

As part of the symposium, historians Martha Jones of Johns Hopkins University, P. Gabrielle Foreman of Penn State, and Kate Masur of Northwestern University emphasized how grassroots Black activism — especially by Black women and communities in the antebellum North — laid the foundations for the 14th Amendment.

Masur said pre-Civil War mobilizations helped lay that groundwork. She emphasized that Black activists, rather than only white abolitionists, led efforts to repeal discriminatory laws in Ohio and beyond.

“People in these movements found ingenious ways to press for their aims — demanding equality, fighting for education, better jobs, and access to the rights white Americans already enjoyed,” Masur said. “They did this at every level — they were strategic.”

She added, “These movements put the terms ‘equal’ and ‘equality’ on the map, and taught the people who would later become the elite-like framers of the 14th Amendment how important it was.”

The symposium also featured Judge Carlton Reeves of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi, Judge James Wynn of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, and an impromptu appearance by Judge Roger Lee Gregory, former chief judge of the Fourth Circuit. Together, they highlighted the unique value Black judges bring to the bench, grounding decisions in cultural context, historical perspective, and lived experience.

“Judges have to comply with whatever the law is... but that does not [stop] judges from saying and speaking the truth in their opinions,” Reeves said.

Judge Gregory reflected on the deep personal and historical experiences that Black judges bring — perspectives often absent from mainstream legal discourse. “Judges don’t come to the court with a blank slate,” he said, underscoring that every jurist carries their background, identity, and community history into the courtroom.

Gregory reflected on growing up in segregation and how that experience deepens his understanding of justice, enriching constitutional interpretation, especially in civil rights cases.

“Sometimes importing that experience into the decision-making process is important,” he said.

Ifill added that judges “speak through their opinions,” and that those opinions both educate and set a standard — especially in civil rights jurisprudence. She noted that judges like Reeves, Wynn, and Gregory contribute to educating both citizens and law students on how to understand and exercise their constitutional rights.

In his remarks, Roger A. Fairfax Jr., dean of the Howard University School of Law, emphasized the historic significance of the 14th Amendment and the school’s enduring role in advancing its promise, invoking the towering figures in the school’s history who helped shape civil rights jurisprudence. He said giants such as such as Charles Hamilton Houston, Thurgood Marshall, Oliver Hill, Pauli Murray, and Spottswood Robinson have been “some of the fiercest defenders of the promise of the 14th Amendment over the past 156 years.”

Fairfax also praised Ifill for her vision and leadership in creating the 14th Amendment Center, calling her “a force of nature,” and “an heir to the legacy of Houston and Marshall, and one of the most important legal minds of our time.”

###