Howard University Hospital Trauma Services recently hosted its 5th Annual Victors Over Violence Award Ceremony, an event that honors trauma survivors and the healthcare teams who support them. Each year, it offers space for reflection, recognition, and healing for the community.

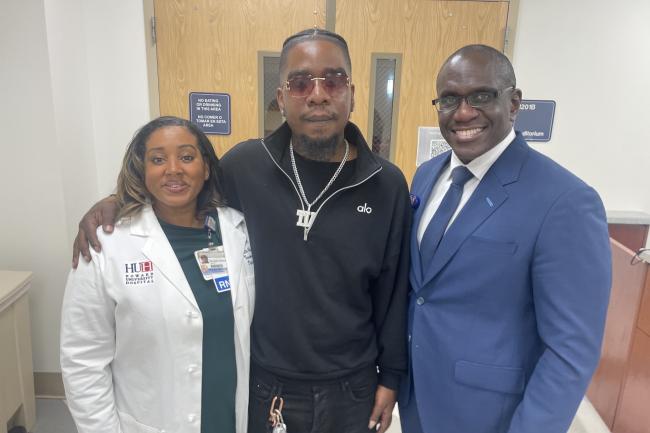

Among those honored this year was Derrick Scott, who has spent years recovering from the emotional and physical impact of a violent incident.

“The pain doesn’t leave—you just learn to live with it,” Scott said at the ceremony, held at the hospital May 30. “I lost my best friend. Every day I carry that pain. But I’m still here. And I’m still fighting.”

HUH is home to a Level I Trauma Center that treats, through the Emergency Department, more than 40, 000 patients each year. Its work goes far beyond emergency medicine: the team includes trauma surgeons, nurses, mental health advocates, and a violence intervention and prevention unit that provides care extending from the ICU to the community.

Trauma Services at HUH also functions as a division of the Department of Surgery within the Howard University College of Medicine. A core part of the trauma team’s role is to walk with patients like Derrick Scott through every stage of recovery.

“This department is about more than saving lives—it’s about building them back up,” said Kenyatta Hazlewood, BSN, MPH, RN, who Directs the Trauma Program, as its’ operational officer and serves as host for the event. “Derrick’s story reminds us why trauma work must include both the body and the soul.”

The Victor Over Violence tradition dates back six years and recognizes not only patients but also the families and caregivers who play a role in recovery. Past honorees include survivors of community violence in the District. Alexander Evans, M.D., MBA, FACS, Trauma Medical Director at HUH, said the work of trauma care begins with the immediate crisis but doesn’t end there.

“The first goal is always to save a life,” Evans said. “But what comes after—the emotional, psychological, and spiritual healing—that’s where the real recovery begins. Every patient carries their injury differently. Some need surgeries. Some need silence. All of them need support.”

At the ceremony, Scott recalled the night he and his best friend were caught in a violent encounter that left his friend dead and left Scott with serious physical injuries that required surgery including an ongoing disability of his hand as well as deep emotional wounds.

“Not everybody walks away from it,” Scott said. “I lost my friend that night. I think about it every day.” In the aftermath of the violence, he said he struggles to process the grief and pain, while trying to move forward with what he described as invisible scars.

“Some of us are still in it. Some of us are trying to run from it,” he said, reflecting on the emotional weight trauma leaves behind. “But the best way through is to face it, to talk about it, and to find people who won’t let you give up.”

Also honored was Rayne Bradshaw, a 22-year-old woman paralyzed in a mass shooting. Though unable to attend due to ongoing medical care, she was celebrated for her courage and progress in therapy. “Rayne is a fighter,” said Hazlewood. “Her strength is the very definition of resilience.”

Roger A. Mitchell Jr., M.D., president of Howard University Hospital, emphasized the need to treat violence as a public health crisis. He said HUH is on the frontlines not just in the ER but also in neighborhoods, in follow-up care, and in how caregivers continue to support patients long after the bleeding stops.

“When we talk about trauma, we’re not just talking about gunshot wounds or car accidents—we’re talking about the chronic, layered impact of violence on entire communities,” Mitchell said.

He noted that the College of Medicine and hospitals like HUH have a responsibility to treat the whole patient: body, mind, and circumstance.

“That means showing up for survivors not only when they arrive in crisis, but long after they’ve been discharged,” he said. “Healing doesn’t happen in a single surgery. It’s a process, and it requires community. Events like this luncheon remind us that the people we care for are more than cases. When you see someone like Derrick come back stronger, it’s a reminder of the impact we can have when trauma care is continuous, compassionate, and community-based.”

###