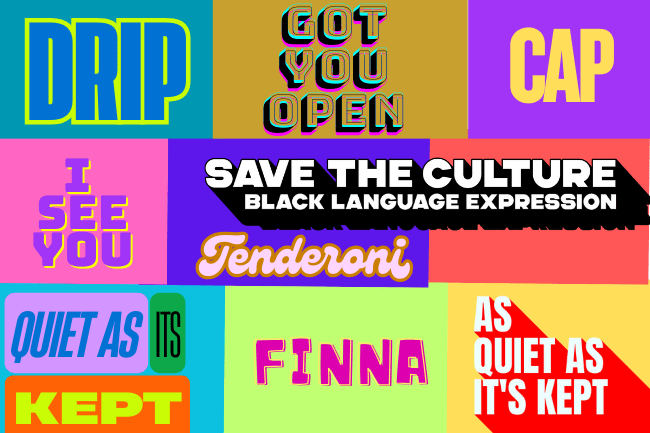

As we come to the end of the SAVE THE CULTURE series, I am hoping to provide a slight detour from the usual format of the top 20 selections of art, music, and film to talk a bit more about what some might consider to be the glue of Black American culture: Black language. Black American language, specifically Black English, is a rule-governed and deeply expressive language system that represents one of the culture's biggest exports, that illustrates the creative expression of how Black people see the world. This entry focuses on increasing our awareness of Black language as a range of the expressions and terms found in film, drama, music, and literature often used to sustain and capture the pulse of Black culture and Black people’s views on the world. For this time capsule, part of the goal is to help highlight some of the characteristics of Black speech that acknowledges its mass appeal, and its specific appeal to Black language users, to highlight common themes embedded in the language such as beliefs about morality, community, and injustice remain.

If we are to explore Black language in this way, we must acknowledge that the work of studying Black language has a long history within academe that I draw from for this brief explanation of how the language works.

In 1949, Lorenzo Dow Turner introduced the academic world to his study of “Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect” linking African language features to the language features of African American speech and greatly opened the academic study of Black language. Years later in 1977, Geneva Smitherman would drop “Talkin and Testyfyin,”contributing greatly to our understanding of how Black speech is most often used, in what spaces it is used, and its consistency of use across media, drama, music, and oratory. Figures such as Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X, Shirley Chisholm, and Micheal Eric Dyson represent some of the culture’s most prolific users of Black language to sway Black and non-Black audiences to their cause.

Smitherman’s work on Black English as a distinctive, rule-governed, and inventive way of describing and appealing to other Black and non-Black speakers reveals the similarities between Black English and mainstream English. However, as she notes, though the rules remain subtle and sometimes captured through intonation or the rhythm of speaking, the visual similarities between gonna and gon’ can erase the difference between “I am gonna (going to) meet up with you soon,” and “Gon’ head and leave them alone before you get what you’ve been asking for.” The second phrasing highlights an immediacy to the individual leaving well enough alone, and it remains important to understanding the different worldviews and values that separate the competent Black English speakers from those borrowing the language.

The list below attempts to capture a range of Black expressions that provide some perspective on the world views and values within Black culture and highlights the ways these things are expressed through creative, consistent approaches to expressing timeless ideas through language that deviates from mainstream English and other standardized written forms of American English. Many of these ideas exist within the Black church, urban street culture, and Black music, and although terms and phrases can change over time, the expressions below do represent a consistent cultural embrace of certain views about God, doing good, doing wrong, and loving ourselves. As new terms continue to expand the meaning and beliefs are ascribed to the speech of Black language users, the familiar terms and expressions that appear in everyday speech take on the regional, ethnic, gendered, and diasporic elements of where the speaker is located. But the spirit and semantic values of the speech tend to maintain consistency even as new speakers create new meanings for words. This is probably evidenced in the use of chat by R&B singer Sza on the song “30 for 30” with Kendrick Lamar. She uses chat to highlight the trend of social media’s influence on popular culture and the ways in which this is used against celebrities.

Additionally, I need to acknowledge that the ways we understand Black English will continue to evolve and change as the users change, as music continues to be exported to other countries and cultures, and as Black scholars and speakers continue to demonstrate the public value of Black English for influencing an American imagination that too often resists newer definitions of what it means to be human before accepting them. As Marcus Boulware notes in his 1969 publication “The Oratory of the Negro Leader: 1900-1968,” Black eloquence is largely structured deviation from standardized ways of using, and it is through this eloquence — or rather through our attention to indirectness, tone, meaning inversion, rhythm, and imagery — that Black English becomes a persuasive force in the world for affirming Black people. Below is a list of Black Language terms and expressions that provide unique insight into the language and the way it is employed by Black speakers.

The terms below highlight creative vocabulary that has gained mainstream usage in Black media and film and expanded the way popular culture resonates with Black culture. Some of the expressions capture the range of Black expressions that reveal unique perspectives on the world and in the Black diaspora. The proverbs included in the list highlight the ways morality and spirituality tend to permeate the language.

And lastly, the overt concern with lying, telling the truth, and initiating a conversation comes through in the terms and expressions to highlight an active behavior or misbehavior of the people (chat, but also quiet as it’s kept).

1. Cap

The concept of “cappin” has been a term used to highlight exaggerated storytelling, fronting, or pretending to be more than one appears or flat out lie. The concept of high cappin can be found in several gangster rap songs from the 1980s through the early 2000s. The phrase has morphed over the years to be used as popular slang meant to call out someone telling a tall tale (“that’s cap”) or to assert the seriousness of truthfulness of one’s statement (“that's a cap.”)

2. Chat

Within contemporary Black English, “chat” is used as a statement of affirmation regarding the role of rumor and conversation about one’s personal affairs. It is a newer usage of the term that captures the role social media and other platforms play in circulating information about celebrities and individuals. Chat is an affirmation that one is being talked about and the indignation of the person or persons being discussed.

3. Overstand

A concept often used in Black speech to denote that one has mastery over and appreciation for the information that is being shared. “Trust me I overstand what you are saying.”

4. Drip

“Drip” is a newer term, made popular by rappers such as Migos, Cardi B, Smoke DZA, and others. It likely evolves from earlier uses of water and ice to describe excessive diamond jewelry from the bling era of hip hop music. The rapper Ghostface from Wu-Tang Clan uses the phrase drip to describe the now popular two-tone wallaby shoes of that era. But it has gained popularity and heavy usage in rap music since 2016 to reference the impressive fashion and style of an individual. The term remains a positive compliment for having great style and an awareness of forward-looking designer clothes and accessories.

5. Homegoing

A homegoing usually refers to a Black funeral service. It represents the view that the passing of a loved one is a return home to the lord for them, where they will wait for other loved ones to join them.

6. Game

An entity or endeavor involving established practices, strategy, and ways of doing something — the rap game, the fashion game, shoe game, etc. It can also mean a style of carrying and expressing oneself with flava and charisma. Well before the HBO hit series “Game of Thrones” became a thing, Spike Lee’s film “He Got Game” highlighted the multiple uses of “game,” punctuated by Public Enemy’s title song to the soundtrack featuring singer Stephen Stills.

10. If I’m Lying I’m Flying

The notion of flight is a common metaphor in Black language often as a reference to escape or rising above the chaos of the world. The imagery of flight pervades the language in numerous ways, but the expression of “if I’m lying, I’m flying” is an expression of hyperbole or exaggeration used to stress that one is telling the truth.

11. Finna

This term is often attributed to Southern Black speech; but is a staple of Black English expressions meant to highlight a future immediate act. Geneva Smitherman translates finna as “fin to go” or about to do something. The word has become internet popular and often translated as “fixing to,” another Southern expression. Though not incorrect, the value of a word is in the way it expresses the anticipation of an action. “We fin to go to pick him up right now.” Or “You finna to give Ms. Sheryl a heartache with your shenanigans.” The poet Nate Marshal named his 2020 collection of poetry “Finna” in homage to this rich expression of Black speech.

12. I See You

This phrase often expresses a deep sense of spiritual and cultural understanding of recognition. The phrase is important because, as Ralph Ellison’s prolific novel “Invisible Man” attests, Black Americans have long experienced a type of social erasure that can render their experiences and progress invisible. The subtle phrase does the work of acknowledging the actions, whether right or wrong, of a person as witnessed and therefore not easily forgotten.

13. Quiet as its Kept

A phrase often used for the sharing of a little-known truth or secret. The phrase highlights an interesting relationship to rumor within Black culture, as rumors are viewed as a form of folk knowledge that can be useful when proven true, but often difficult to verify, creating the need for one not to openly spread them. The phrase is also used as a preface for potentially embarrassing information about to be made public or in regard to forgotten or overlooked history.

14. Got You Open

The phrase derives from an earlier 1980s phrase of someone having their nose open, meaning to be so in love as to be potentially exploited. Later usage of being open retains some of the same sentiments, but the meaning has been expanded to mean one is so invested in the music, writing, performance that they are vulnerable to being swayed by it.

15. Talkin in Tongues

To speak in secret or coded language during a Black church service when one is possessed by the Spirit of God. Dancing or involuntary bodily movement can be associated with the act. The act is usually considered sacred, and attendees usually do not interrupt the possession. The phrase can be used ironically to describe anyone that is speaking unintelligibly.

16. Serious as a Heart attack

An expression of seriousness about one’s intent or information recently shared. “Are you serious?” “I’m as serious as a heart attack.”

Proverbs

17. The Blacker the Berry the Sweeter the Juice

This Black proverb appears as early as 1929 in the title of Wallace Thurman’s novel, “The Blacker the Berry.” Most agree that the phrase is meant as an affirmation of the richness and beauty of Black people and of darker skin Blacks. In many ways it is a counter response to the pervasive celebration of white or lighter skin Black Americans. The phrase appears in Tupac Shakur’s 1993 song “Keep Your Head Up,” and continues to flow through Black culture as a form of praise and affirmation.