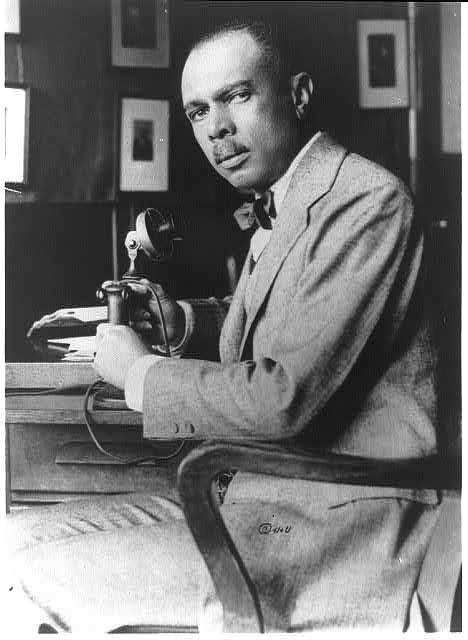

(Image above: Dr. Alain Locke, courtesy Moreland-Spingarn Research Center)

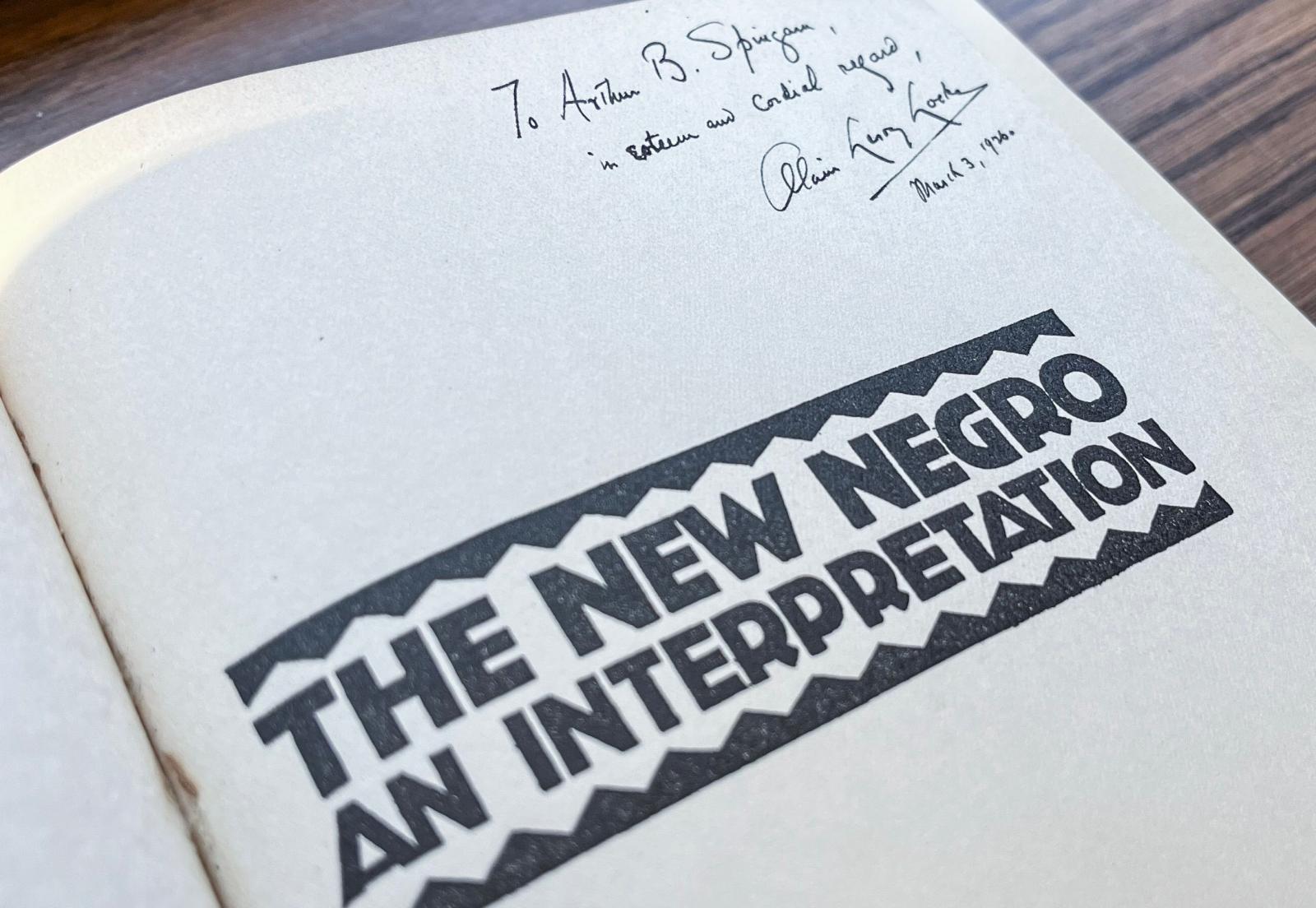

This year marks 100 years since the publication of “The New Negro,” the groundbreaking anthology edited by Alain LeRoy Locke, Ph.D., in 1925, which still remains a defining work. His 140th birthday on Sept. 13, 2025 presents a much-needed opportunity to celebrate his vision, reflect on his legacy, and most importantly, learn the lessons which will propel humanity into the future. The book was an anthology of literature that, perhaps for the first time, presented the genius of Black creatives in a format which could be reproduced and distributed nationally. Not only did the book feature poetry, drama, short stories, musical lyrics, and essays with social commentary, but scholars like Locke also explained how American history, even at that point, was replete with the contributions of Blacks in a wide variety of artistic genres. “The New Negro” showed Blacks that they had creative agency, power, and the ability to control their own self-expression. It is widely considered the spark that ignited the Harlem Renaissance, a bold explosion of Black culture in all forms, including literature, poetry, acting, dancing, singing, the fine arts, and others. The center of the renaissance was the Harlem borough of New York City, a predominantly Black area in the most populous city in the U.S.

Dr. Alain Locke was the first African American Rhodes Scholar, a Harvard-trained philosopher, and a Howard University professor for thirty-five years. Beyond his role as editor of "The New Negro," Locke is known as the intellectual architect of the Harlem Renaissance, shaping a generation of Black artists and thinkers. Locke was also a tireless advocate for equal pay for Black professors and the rightful place of Black studies in higher education and demanded that Howard’s Black professors be respected for their knowledge, authority, agency, and academic philosophy. He insisted that Blacks step outside of stereotypes decided by outside influencers and tell their own stories in the broad spectrum of life as humans— joys, pains, sorrows, triumphs, laughter, joy, and, yes, American racism and prejudice. His goal was to make sure that the world did not see American Blacks in one dimension, that of an oppressed race in hopeless victimhood, but rather as people with a full range of life experiences, expressions, dreams, despairs, and triumphs even in the obvious face of oppression.

He wanted to make Howard the center of Black arts and culture and attempted to make Howard the first American university with a theater program, for example. That vision stood in contrast to the more docile approach of an early Howard president, who terminated Locke. However, Locke's foresight was vindicated shortly thereafter when Howard’s first Black president, the newly installed Mordecai Johnson, reinstated Locke shortly after Johnson began his tenure. Locke continued to shape generations until his retirement in 1953 and Howard named the building after him that serves as home to its College of Arts and Sciences today.

As in the rest of America, the 1920s represented a period of massive change in Black communities. Many Blacks were migrating from more rural areas in the South where their families had worked as sharecroppers after the end of slavery and were moving to seize jobs created by the nation’s rapidly advancing industrialization in northern cities. Though still fractional compared to white wealth, Blacks were beginning to exercise economic power and were also exercising nascent political influence. While Blacks, even as slaves, were always allowed to entertain, they were now being taken more seriously as creatives, including artists, writers, and performers. Intellectually, the emergence of HBCUs and the institutionalization of public education were creating a growing class of Black professionals and thought leaders. Slowly but surely, many felt, a “new Negro” was emerging.

“So far as he is cultural articulate, we shall let the Negro speak for himself.”

Locke was concerned, however, that even as Blacks were beginning to expand their footprint in American society, perceptions of Blacks were reduced solely to stereotypes about their socio-economic position and ignored everything else about life in Black communities. He was equally concerned that the predominant narratives about Blacks was being told in stories about them, rather than in stories by them. He wanted Blacks to tell their own stories. In “The New Negro,” Locke described a generation stepping out of stereotypes and into self-actualization.

"The Old Negro had long become more of a myth than a man," he wrote.

Contrarily, the New Negro, according to Locke, was ambitious and "vibrant with a new psychology." Locke wanted Black culture to be respected as integral and inseparable from a larger American culture, not segregated and encountered only by those exploring the implications of race. In other words, he wanted Blacks in America to interpret their own experience instead of having it interpreted by others.

“Of all the voluminous literature on the Negro, so much is mere external view and commentary that we may warrantably say that nine-tenths of it is about the Negro rather than the Negro that is known and mooted in the general mind,” Locke wrote. “We turn therefore in the other direction to the elements of truest social portraiture and discover in the artistic self-expression of the Negro today a new figure on the national canvas and a new force in the foreground of affairs.”

“So far as he is cultural articulate, we shall let the Negro speak for himself,” he wrote in his introduction.

A Mosaic of Black Voices

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-USF34-9058-C]

“The New Negro” was dedicated to the “younger generation” and included essays, fiction, poetry, drama, musical lyrics, and commentary from the most prominent Black artistic and cultural influencers of the time, including Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Countee Cullen, W.E.B. Dubois, Walter White, and Paul Kellog. For perhaps the first time, Blacks saw their collective brilliance, profundity, and artistry — authentic and unvarnished — on a national level. The recognition that they could express themselves in full and on their own terms directly inspired an outpouring of creativity across the nation, and the epicenter became Harlem, leading to the phenomenon commonly referred to as the Harlem Renaissance.

Locke assembled the nearly 450-page book in two main parts, each reflecting a different dimension of Black identity and cultural declaration.

Part I: The Negro Renaissance

The book began with essays that set the intellectual stage. Locke's own introduction was followed by Albert C. Barnes' "Negro Art and America" and William Stanley Braithwaite's survey of Black presence in American literature. Both essays helped the reader understand reinforced that, recognized or not, Blacks had already shown their creative prowess in the face of systematic disempowerment and were now poised to do so in expansive fashion. Locke also gathered the voices of a younger generation in "Negro Youth Speaks," showing that the energy of renewal was not confined to established leaders but was alive among emerging poets, writers, and thinkers.

The section then expanded into fiction, offering stories such as Rudolph Fisher's “The City of Refuge” alongside excerpts from Jean Toomer's "Cane." Each piece captured the variety of urban migration, folk tradition, or experimentation in narrative style. In “Spunk,” for example, Howard alumna Zora Neale Hurston (A.A. '1924) showcased her signature style, mimicking the dialect of Blacks in the South to tell the story of an arrogant man, Spunk, who brazenly shot the husband of the woman he was openly dating an a small town, Joe, only to have the Joe come back after death to haunt and kill Spunk.

“Ah wuz loadin’ a wagon wid scantlin’ right near the saw when Spunk fell on the carriage but ’fore Ah could git to him the saw got him in the body—awful sight,” Hurston wrote in “Spunk.” “Me an’ Skint Miller got him off but it was too late. Anybody could see that. The fust thing he said wuz: ‘He pushed me, ’Lige—the dirty hound pushed me in the back!’—He was spittin’ blood at ev’ry breath. We laid him on the sawdust pile with his face to the East so’s he could die easy. He helt mah han’ till the last, Walter, and said: ‘It was Joe, ’Lige—the dirty sneak shoved me . . . he didn’t dare come to mah face . . . but Ah’ll git the son-of-a-wood louse soon’s Ah get there an’ make hell too hot for him. . . . Ah felt him shove me . . . !’ Thass how he died.”

Poetry followed in the book, with Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, and others weaving verse that ranged from spiritual meditation to sharp social critique. Countee Cullen wrestled with how his reverence for his homeland of Africa complicated his adoration for Jesus, who was then typically portrayed as a white man. Cullen longed to envision of a Black Jesus.

“Surely then this flesh would know; Yours had borne a kindred woe,” he wrote in “Heritage.”

James Weldon Johnson’s (D.Litt. '1923) “The Creation” has been recited countless times over the decades since it was published in “The New Negro.” “The Creation” uses poetic license to retell the Genesis story. It was an artistic work of brilliance, but its inclusion in this book also sent another important message. The God who created the universe was also the God of the Negro in America, and they had just as much right to share their spiritual perspectives as anyone else.

"And God stepped out on space,

And He looked around and said,

“I’m lonely--

I’ll make me a world.”

- “The Creation” by James Weldon Johnson as featured in “The New Negro”

The collection also highlighted the importance of drama. Montgomery Gregory's “The Drama of Negro Life” walks the reader through a history of how Blacks had been portrayed in theater, pointing out that the first major interpretations of Black life on the stage were plays written by white authors and acted by whites in Black face makeup. Those portrayals moved from somewhat sympathetic portrayals based on “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” to downright mimicry and farce. According to Gregory, the emergence of outstanding Black playwrights and actors in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave hope that serious Black drama could become a respected part of American theater, but only if Blacks took ownership for their own stage presence.

“However disagreeable the fact may be in some quarters, the only avenue of genuine achievement in American drama for the Negro lies in the development of the rich veins of folk-tradition of the past and in the portrayal of the authentic life of the Negro masses of today,” Gregory wrote. “The older leadership still clings to the false gods of servile reflection of the more or less unfamiliar life of an alien race. The “New Negro,” still few in number, places his faith in the potentialities of his own people – he believes that the Black man has no reason to be ashamed of himself, but that in the divine plan he too has a worthy and honorable destiny.

In much the same vein, Jessie Fauset confronted the relationship between Blacks and comedy in American society. He points out that, for years, the only visibility granted to Blacks revolved around their ability to entertain through laughter, and in many cases, to be the subject of ridicule through buffoonery.

“For years, the Caucasian in America has persisted in dragging to the limelight merely one aspect of Negro Characteristics, by which the whole race has been glimpsed, through which it has been judge,” Faucet contended. “The medium then through with the Black actor has been presented to the world has been that of the ‘funny man’ of America.”

Faucet insightfully posits that the stereotype being created of Blacks as happy buffoons may have been designed to mask the true plight of Blacks in America and the accompanying culpability of whites for their condition. If Blacks lived in a state of perpetual laughter and oblivious happiness, even while living through the vestiges of slavery, then it could be arguably reasoned that nothing needed to be done to improve their lives.

“In passing, one pauses to wonder if this picture of the Black American as a living comic supplement has not been painted in order to camouflage the real feeling and knowledge of his white compatriot,” Faucet wondered. “Certainly, the plight of the slaves under even the mildest of masters could never have been one to awaken laughter. And no genuinely thinking person, no really astute observer, looking at the Negro in modern American life, could find his condition even now a first aid to laughter. That condition must be variously deemed hopeless, remarkable, admirable, inspiring, depressing; it can never be dubbed merely amusing.”

Faucet explained how Blacks were gradually moving on from the “minstrel formula,” using comedy more intelligently to make broader points. He pointed to the work of late nineteenth century actors like Ernest Hogan, who used comedy but did not gloss over the trials of Black life in America. Moreover, he said, the “New Negro” actors of the early twentieth century were beginning to take control of the humor they put forth, owning its value as social commentary, a storytelling tool, or simply a way to bring joy and lightness to an audience. No longer simply a jester, he argued, Blacks were using a combination of comedy and tragedy to share the authentic experiences of the Black community.

Willis Richardson's folk play “Compromise,” dramatizes the relationship between Black and white neighbors in Maryland. It explores the dynamics of privilege, fairness, and values, and their differences in Black and white families. After her white neighbor, Carter, accidentally shoots her son, Jane, a Black mom forges an awkward relationship with him, demanding financial support after Carter’s son impregnates Jane’s daughter. That compromise, reminiscent of the monetary deal her late husband made with Carter after the shooting, soon falls apart after Jane’s son attacks the baby’s father, making him a fugitive from the law in early twentieth-century America.

Music was celebrated through Locke's essay on spirituals, J. A. Rogers' reflections on jazz, and Langston Hughes's playful yet profound jazz poems. Gwendolyn Bennett used her contribution, “Song,” to elucidate the importance of music in expressing the joy and pains of life in the Black community.

“I am weaving a song of waters, shaken from firm, brown limbs, or heads thrown back in irreverent mirth,” she wrote.

Folklore and history were also robustly represented. Arthur A. Schomburg's "The Negro Digs Up His Past," for example, passionately implored Blacks to investigate their history. He noted the many contributions Blacks had made in America, many of them obscured, which were nevertheless integral to the advancement of the nation. Because of their historical oppression in this country, he argued, Blacks needed to lean on a true understanding of their history even more than other groups.

“The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future,” Schomburg wrote. “Though it is orthodox to think of America as the one country where it is unnecessary to have a past, what is a luxury for the nation as a whole becomes a prime social necessity for the Negro. For him, a group tradition must supply compensation for persecution, and pride of race the antidote for prejudice. History must restore what slavery took away, for it is the social damage of slavery that the present generations must repair and offset. So among the rising democratic millions we find the Negro thinking more collectively, more retrospectively than the rest, and apt out of the very pressure of the present to become the most enthusiastic antiquarian of them all.”

Arthur Huff Fauset's exploration of American Negro folk literature showed that the nation had only just begun to unlock the trove of stories Blacks in America had inherited from the African ancestors. He was particularly concerned that the popular Uncle Remus stories based on narratives by African slaves, spent too much time creating and interpreting Remus’s character as a representation of Blacks rather than just simply relaying the stories that were told in the voices of those who told them. Fauset advocates for a thorough collecting of African folklore, from proverbs to fables, which “prove the common ancestry of man, both with regard to his mental and cultural inheritance.”

Locke's concluding essay in this section, "The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts," tied Black creativity to African traditions, situating African American art within a broader global lineage.

Part II: The New Negro in a New World.

In Part II, voices turned to institutions, communities, and broader questions of identity. Paul Kellogg opened the section by shining a light on the myriad ways Black pioneers helped the country expand westward by tackling the frontier and by integrating their culture with those of the cities to which they migrated. James Weldon Johnson called Harlem "the culture capital,” and Elise Johnson McDougald's "The Task of Negro Womanhood" offered one of the earliest examinations of the intersection of race and gender, affirming the resilience and cultural leadership of Black women as essential to the progress of the New Negro. Her vision anticipated Howard University's enduring tradition of centering Black women as scholars, leaders, and change agents on the national and global stage.

"Largest, oldest as an avowed university in plan and pattern, national in scope and support, Howard University already has advantages that make plausible its claim to be "the Capstone of Negro Education."

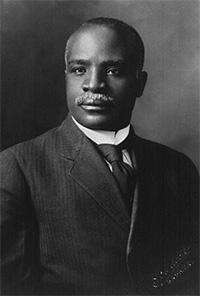

Kelly Miller (B.S. '1886, M.A. '1901, LL.D. '1903), Howard alumnus and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, used his contribution to “The New Negro” to argue that Howard was "the national Negro university." He acknowledged that other black colleges and universities, but noted Howard’s special positioning as the only Black institution at the time which had the same collegiate structure and academic offerings as most predominantly white colleges and universities.

“But just as surely as there is a need and place for each, and for that matter more, of these institutions, just so certain is it that one of them must eventually become the conscious and recognized center of the higher life and cultural inspiration and aspiration of the race,” Miller wrote. “Such by reason of its origin, location, constituency, maintenance and objective, Howard University aspires to be. Largest, oldest as an avowed university in plan and pattern, national in scope and support, Howard University already has advantages that make plausible its claim to be "the Capstone of Negro Education."

While Miller made the case for Howard’s prominence, he also takes it to task for the responsibility which comes with its positioning at the center of Black America’s intellectual and cultural sphere. In particular, he points to the need for an institution which has special expertise and insight into Black life from all aspects and disciplines.

“Every group, coming into cultural maturity, needs its Forum and its Acropolis. A national Negro university must shed the light of reason on the particular issues of Negro life and add the guidance of science to the tangled issues of race adjustment,” he wrote. “A body of intellectual, moral and spiritual élite, consecrated to these ideals and co-operating in this aim, is calculated to put a new front on the whole scheme of racial life and aspiration. Under the stimulus of such a conception of its mission, Howard University, or the institution that most zealously undertakes it, will become the Mecca of ambitious Negro youth from all parts of the land and from all lands.”

The section also included essays exploring the importance of Hampton Institute and Tuskegee Institute as well as Durham, North Carolina, which it called the “Capital of the Black Middle Class.” also looked beyond the United States. W. A. Domingo's "Gift of the Black Tropics" examined the relationship of Blacks born in America with those who from other countries and patterns of segregation and prejudice that were part of that dynamic. He also noted that Blacks from the Caribbean islands were often thought of homogeneously, when, in reality, they were incredibly diverse, occupying many different socio-economic positions in their native countries. He insists that they were an invaluable element of Black America.

“The outstanding contribution of West Indians to American Negro life is the insistent assertion of their manhood in an environment that demands too much servility and unprotesting acquiescence from men of African blood,” Domingo said in his essay. “This unwillingness to conform and be standardized, to accept tamely an inferior status and abdicate their humanity, finds an open expression in the activities of the foreign-bord Negro in America.”

W. E. B. Du Bois' "The Negro Mind Reaches Out" placed the African diaspora within a global framework of solidarity. Locke's curation reminded readers that the New Negro was not just a Harlem figure but part of a worldwide movement of cultural and political renewal. Together, these works created what Locke called "a laboratory of a great race welding."

From Harlem to Hip Hop and Everything In Between

The concept of "race welding" resurfaced again in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s. What Locke called "a new vision of opportunity" in 1925 found echoes in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s, in the late 70s with the rise of hip hop, and in today's Black creativity from music and literature to film and visual art. Despite their opposing ideologies, the works of writers such as Amiri Baraka, who studied at Howard, and Sonia Sanchez were only possible because of the foundation of race pride and self-expression established by Locke and other Harlem Renaissance thinkers of that time. Their boldness in rejecting old scripts mirrored Locke's observation that, "In the very process of being transplanted, the Negro is becoming transformed."

That transformation echoed later in the birth of bebop and hip-hop, when street corners turned into stages and turntables became instruments of testimony. As Locke once described Harlem as "a laboratory of a great race welding," hip hop shaped unity from inner-city landscapes and grew into both a global culture and one of Black America's strongest voices against inequality

Today, Black artistry from Beyoncé's reclamation of Southern Black heritage to Jordan Peele's cinematic subversions, from Amanda Gorman's poetry to Kendrick Lamar's Pulitzer-winning verses, remains faithful to Locke's call for "fuller, truer self-expression." The New Negro is alive in every beat, brushstroke, and script that insists on telling our story our way.

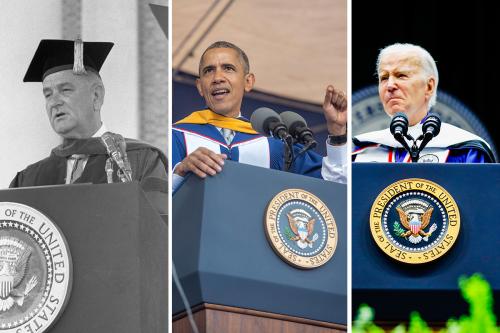

The New Negro Howard's Living Legacy

At Howard University, Locke's presence endures. His papers, correspondence, and unpublished works are preserved in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, one of the world's most important repositories of African American history. Students and scholars walk the same corridors where Locke once lectured on philosophy and aesthetics, carrying forward his belief that art is a vehicle for liberation.

It is no accident that Howard, The Mecca, is home to Locke's intellectual archives. The university itself embodies his project: to cultivate leaders who transform stereotypes into strength and marginalization into mastery.

Why We Need the New Negro Again

Locke wrote in 1925 that the "day of 'aunties,' 'uncles' and 'mammies' is equally gone." He demanded that America scrap its fictions and face the reality of Black life. One hundred years later, amid a rising tide of fascism, racial scapegoating, and cultural erasure, we find ourselves needing the courage of Locke's generation once more.

The New Negro was not simply a member of the Harlem Renaissance. It was a mindset: self-respect, cultural pride, and collective determination in the face of adversity. Today’s artists, activists, and intellectuals inherit that torch and are called to enlighten the world in the same spirit.

In Locke's words, "The Negro today wishes to be known for what he is..." That assertion is as urgent now as it was a century ago.

As we celebrate the centennial of “The New Negro” and honor Alain Locke's birthday, let us not relegate his ideas to history. Instead, let us embrace them as a blueprint for resilience. In a climate shadowed by resurgent fascism, the rebirth of the New Negro and The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts is not just desirable, it is essential.